There is no doubt but that the results represented a triumph for Sinn Féin whose ability to run elections efficiently was no better illustrated than the manner in which they not only managed to get their vote out – after a minor panic in the last hour or two when turnout appeared to be well down on 2017 – but how they efficiently divided constituencies and resources to maximise their seat haul.

One particularly impressive example of this was in Newry/Armagh where Conor Murphy and Cathal Boylan were only separated by four votes on the first count. Similar vote management led to the same outcomes in Fermanagh/South Tyrone, West Tyrone, Mid Ulster and North Belfast. Of course they were assisted in that by the sheer bumbling ramshackle nature of the SDLP which is to electoral “machine” what an abacus is to a laptop.

The SDLP, like Sinn Féin’s electoral rivals in the south, – particularly Fianna Fáil who did the SDLP no favours whatsoever by love-bombing it – have effectively surrendered a significant part of what used to be their demographic constituency. Part of that has been to attempt to outWoke the Shinners on everything from transgenderism to abortion and immigration. This, however, has only succeeded in pushing away some of their more conservative voters.

The fact that Sinn Féin emerged as the biggest party – although it is not the first time they got the largest share of votes which they did in the 2009 European elections – and will get to nominate Michelle O’Neill as First Minister became the headline for most of the election commentary.

Mary Lou heralded this as an historic milestone and claimed that Northern Ireland was established to ensure that a Catholic nationalist – though she didn’t use the C word obviously – could not become prime minister and that there would be a perpetual unionist majority.

Yes, no doubt that was a consideration but the chief motivation that underlay the ethnic and electoral basis for the northern state was that it would most likely never voluntarily vote to join the rest of Ireland after the country was partitioned under the 1921 Treaty.

There was never anything specifically to exclude the possibility of Catholic nationalists becoming the biggest party in Stormont. Later amendments to the legal framework governing Northern Ireland’s position within the United Kingdom as contained in the 1973 Sunningdale Agreement and the 1985 Anglo-Irish Agreement specifically allowed for the possibility that if there was ever a majority within the six counties in favour of national unification then the British state would not act to prevent that, and indeed would facilitate a poll if such a scenario seemed possible.

That condition was carried over into the 1998 Good Friday Agreement. The key section on ‘Constitutional Issues’ reiterates previous commitments to legislate for any democratically expressed desire by a majority to leave the United Kingdom. While Section 1 (iv) reads as though this might be something decided on an all-Ireland basis, subsection(ii) effectively retains the “unionist veto” by qualifying any such decision by the requirement that there would have to be the consent of “a majority of the people of Northern Ireland with regard to its status.”

A poll itself can only be held when it appears to the Northern Ireland Secretary that “a majority of those voting would express a wish that Northern Ireland should cease to be a part of the United Kingdom and form part of a united Ireland.” The bald fact of the matter is that there is no such evidence from any election held since 1998 that there are grounds to believe that a majority of those voting in a border poll would be likely to vote for a united Ireland.

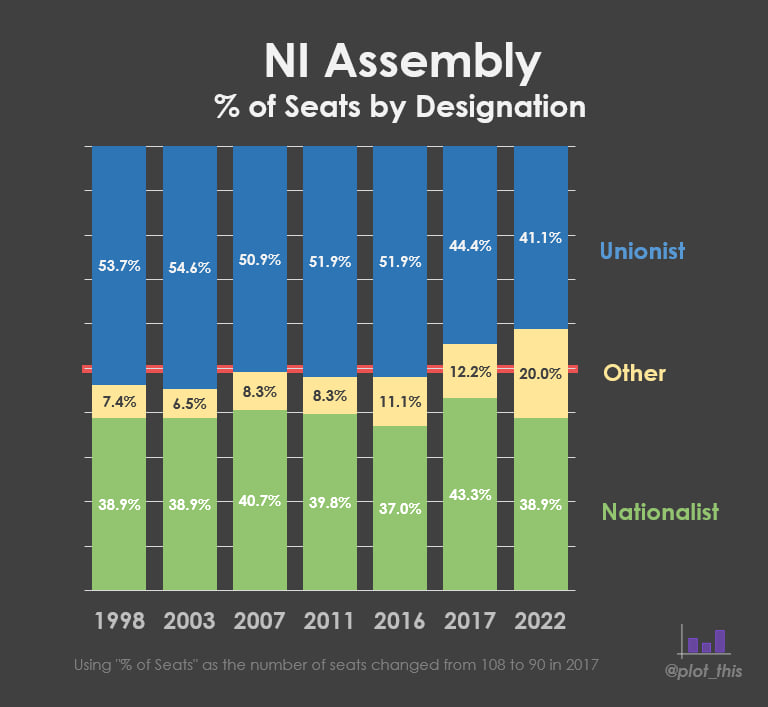

All of the electoral outcomes over the past quarter of a century prove that whatever about the internal shifts within the two designated nationalist and unionist political camps that support for parties openly favouring a united Ireland has barely changed at all over those 24 years. Indeed as this graphs show, the % of MLAs designated as “nationalist” is exactly the same as it was in 1998.

What has changed of course is that Sinn Féin is by far the dominant nationalist party. It has reduced the SDLP to a marginal force which last week was squeezed on the one hand by Sinn Féin, and to a lesser extent by Aontú among Catholic republicans opposed to abortion; and on the other by the Alliance Party which has eaten into the Catholic middle class vote.

A similar process has taken place on the unionist side where the Ulster Unionist party has had its vote further reduced by the DUP and Traditional Unionist Voice and has also lost votes and seats to Alliance.

The Alliance vote is most interesting as that party does not identify within the Assembly as either nationalist or unionist, and on the face of it there is little to predict how its voters or those of the much reduced Green Party might vote in a border poll. However, the electoral evidence would suggest that Alliance voters are more likely to be Protestant and therefore unionists with a small “u” and to a lesser extent middle class Catholics who were never enthusiasts for a united Ireland.

The notion then that Sinn Féin becoming the largest party in the Assembly – with exactly the same number of seats as before and with a vote increase of just 1% – is somehow a precursor or even a guarantor that the north is moving quickly towards unity is simply not true. Sinn Féin may or may not, depending on what the DUP decides to do, elect the First Minister. That in itself makes no difference to the provisions of the Good Friday Agreement with regards to the holding of a border poll.

It is also possible of course that there will be no agreement on the next Executive and that the Assembly remains suspended. With overall control of the six counties reverting back in the devolved ministries to the British Government. This, incidentally, suited Sinn Féin and the SDLP when abortion was introduced by default during the previous suspension – one of the few “north is next” promises Sinn Féin have actually managed to follow through on.

It is absurd in any event that any democratic election should lead automatically to a perpetual ethnically based coalition of parties who obviously hate each other but who have gotten on reasonably well in “power” on the same basis as coalition parties do everywhere else: looking after themselves and their clients.

That may not be sufficient to cobble together a deal this time. Who knows? That will hurt Sinn Féin less than it will the DUP as it will be able to claim – with some justification – that like Viscount Brookeborough – they don’t really like having Fenians about the place. Certainly not at the top of the table.

That will provide Sinn Féin with continued credibility in the north, but more importantly sustain the momentum as they focus on their real prize. Which is not a united Ireland but a place in government in the Republic.

Matt,

ReplyDeleteyourself, Peadar and Jeffery's crowd will have to leave the majority to get on with their killing of the unborn.

Though ideologues and moralists are difficult in each their own way , those encapsulating both like you sir ... are unbearable.