Anthony McIntyre ⚱ with fond memories of a Lower Ormeau Road mother who died in October.

When I lived there, almost fifty years ago, the Lower Ormeau Road was a small nationalist enclave of around less than thirty streets. It has expanded since. The half mile stretch of road, an arterial route in and out of Belfast City Centre, was bordered at each end by the River Lagan to the South and the railway line to the North. Its baseline, River Terrace and Lower Balfour Avenue, hugged the river which wound its way past, leaving both streets as if they were nestling in the arc of a crescent.

It provided easy pickings for loyalist activists during the conflict. They could access the community that lived there quite easily from three sides, Ballynafeigh, Sandy Row and Donegall Pass. Neither the railway bridge running parallel with McClure and Pevril Streets nor the river bridge at Dromara Street afforded the natural protection they seemed to offer on paper. A thirty yard stretch of the road became the site of two loyalist massacres of unarmed civilians - the Rose & Crown Bar in 1974 and Grahams Bookmakers in 1992.

About a hundred yards from that killing zone sat Artana Street, the second last before reaching the Ormeau bridge that spanned the Lagan. There was only Dromara Street after that. It seemed too close to “over the bridge” for comfort, and the lethally sectarian dangerous characters that lived in Annadale Flats and places like Gypsy Street. Psychologically, although not in real terms, it seemed more vulnerable than other parts of the community. Any mother with teenage sons in Artana Steet must have got by on a diet of frayed nerves and Valium.

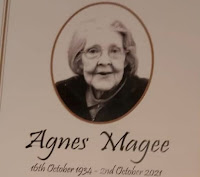

Agnes Magee, who died at the beginning of October, raised her family in Artana Street, number 7, the fourth house down on the right-hand side. That is ingrained on my mind because anytime I would head to it while on the run as a 16 year old, I would look towards the bottom of the street in the direction of Kinallen Court in case of a British Army foot patrol – I could always hear the whir of the jeeps or the rumble of the Saracens - and count the doors to be passed before I reached safety. I might only have stayed for a cup of tea before making off again. No matter what time I arrived, night or day, my anxious knock on the door would not go unanswered.

I had been in Dundalk for two weeks lying low after absconding from St Patrick’s Boys Home. I returned to Belfast late at night, hours after being released from Garda custody, having been arrested earlier in the day. My driver, returning from a visit to the dog track in the town was nervous. He was not an activist, just a punter. Micky McKevitt had approached him and asked him to get me to Belfast safely. I didn’t want him dropping me at a house he could later identify if the squeeze was put on him, so I told him just to let me out on the front of the road after a quick scan for foot patrols. He was only too glad to see the back of me. I galloped to Artana Street. When I knocked, Agnes let me in before I had time to explain my predicament – that I was apprehensive about making my way to my more regular nighttime places of refuge. At that time, after midnight, no doors would be open that would enable me to walk into a hall - as I often did in daylight hours - and out of the way of an approaching foot patrol or jeep.

I got a bed rather than a settee. It had been vacated by her eldest son, Hugh, himself often pursued through the same narrow streets by soldiers who told everybody they accosted that he was to be shot on sight. He had since been captured and was languishing in Long Kesh. I was the latest to be supposedly shot on sight, if the snarling squaddies were to be believed. Which I doubt they were. They made no attempt to shoot me when they eventually caught up with me. But Agnes had a better grasp of the malevolence of British soldiers than most.

It was not that she had any sympathy for violent causes. She was in fact of Protestant stock, originally from the Shankill. While a child growing up in Bagot Street our family home-help was Agnes Gourley from the Shankill. I guess I could wax legalistic and suggest that Agnes Gourley and Agnes Magee have always given me probable cause to warmly associate the name Agnes with the Shankill. Agnes Magee was not some rabid republican diehard but a mother eager to avoid a situation that would result in the death of some mother’s son.

Of course, she had known me from when I was much younger. Right up until I went on the run, I had worked as an apprentice terrazzo layer for a company at the bottom of the street, Toffolo Jackson. So calling to her home anytime I was based in the yard just to say hello or talk to her son Willie if he was there was regular enough. Willie and myself had attended primary school and a youth club together as well as playing soccer, usually competing for the goalkeeper’s jersey. His death left her devastated. Guiding her children through besieged precarious pathways, keeping them safe, only for one to die before her of natural causes was heart wrenching. When she caught Covid last year, my friend Kay would update me on her battle, then her progress and recovery. It was also Kay who was the bearer of the bad news that she had died of an unrelated illness. The last time I recall speaking to her was at the funeral of her husband Patsy. My abiding memory remains that of a quiet, gentle soul whose diminutive frame seemed far too tiny for the huge warmth she radiated.

The mothers of my friends in the Lower Ormeau Road like Agnes Magee, Dolores Rea, Ellen McAllister or women like Alice McCartan, whose door was never closed while I was on the run, have stayed in my memory long after people I was on the same wing with in jail have vanished. It has to tell me something about the impression they left on me. We in the flush of youth may have thought we were heroes pitched in battle against foes, real and imagined. In truth that mantle belongs to these Lower Ormeau Road mothers who had to raise their children in a magnetic field for loyalist killers. A hero was once described by the French writer Romain Rolland as someone who does what they can. Agnes Magee, unfailingly, did what she could.

⏩ Follow on Twitter @AnthonyMcIntyre.

Lovely piece Anthony, dangerous streets in dangerous times. I remembers Grahams bookmakers in 92 I was in Belfast at the time staying in Poleglass.

ReplyDeleteCaoimhin O'Muraile

A heartfelt eulogy .... the years have bestowed much warmth and understanding.

ReplyDeleteThank you Anthony - my mummy's door was never closed. One of the reasons my daddy called her Florence (as in Florence Nightengale) she was always helping someone!

ReplyDeleteDoreen - you are welcome. She was one lovely woman.

ReplyDeleteThe last comment did not make it through. TPQ does not publish comments from "Unknown". It leads to too much confusion when there are multiple users posting as "Unknown". If your comment is for publication sign off on it.

ReplyDelete