Hidden Histories of the Northern Ireland Troubles

Memories Not of My Own

In the midst of the escalating violence, people in Northern Ireland got on with their daily lives; they had to. In the evenings blood would trickle down cast-iron street drains and into the sewers. In parts of North Belfast, the night air would often be punctuated by the sound of gunfire which could be heard for hours on end.

Belfast, 1972 … two young men. One dead, the other facing the best years of his life in jail before facing the same fate shortly after his own release as a 36-year-old … Belfast, 1989 …

Back on the Crumlin Road I walked across the road, passing the top of Cliftonpark Avenue – a street with many stories … perhaps for another time.

For now it was time to revisit my old place of work. Oldpark Road Library, where I was employed as a library assistant from October 2003 until May 2004, is now derelict. This period of my life was dreadful. I was depressed almost all the time (though I didn’t realise it at the time – depression was one of those things that happened to someone like Richey Edwards wasn’t it?). I was also acutely aware of the fact that the library had faded from its previous grandeur. With Cairn Lodge Youth Club run into the ground I worked as a librarian issuing Westerns and Mills & Boon to good-natured elderly folk from the Oldpark, Crumlin and Shankill. Well, that was my job … what I didn’t realise was that I was going to have to act up as a youth worker for some of the young lads who used the library as a drop-in centre.

For days, weeks, months tears tripped me. I had to act the big man and pretend it hadn’t got to me as I sought solace in copious amounts of drink and the task of trying to get someone else to be my new girlfriend.

‘Do you have the new Lee Child son?’

Looking for a surrogate for affection, validation, I struck up a friendship with the library security guard, Billy. Billy was a former UDR man from Omagh who lived in Carrick. He was probably about twenty years older than me, but we spent days talking. He had a very macho, bravado attitude to what I was going through and brought me in a bag of FHM magazines one day. He probably thought this would help, but it just intensified my misery. Billy’s father had been an RUC man and was blown up by a 600 lb IRA landmine in August 1981. Apparently his dad and his RUC colleague were found in pieces across nearby fields. Billy told me that his father loved country music, which he hated. He didn’t seem to get on with his dad. We would stand at the front window of the library, chatting while looking across the road to Manor Street.

Whosoever shall call on the name of the Lord shall be saved. Acts 2 v 21.

As I walked around the side of the library I peered through the window grilles to have a look at the old staff room behind the issue desk. I recall many days clambering in and out of there to gulp from a large bottle of Lucozade which I had in my bag to raise the energy I had lost from the previous night’s drinking. Drinking to forget. A broken heart. Close to collapse. A list of regrets longer than my arm.

As I left the library I walked down Rosewood Street and turned left into Yarrow Street. Yarrow Street is a modern housing development which was built to replace old red-brick stock. It is innocuous, but like many streets in Belfast it is inhabited by a dark history.

Almost forty-nine years ago this part of the Crumlin Road was an unofficial ‘check-point’ manned by the UDA and other loyalists. Yarrow Street isn’t often mentioned in accounts of the Troubles, but for someone with an intimate knowledge of that period in history it is difficult when walking through this part of town not to cast one’s mind back to the dreadful summer of 1972. On Friday 21 July 1972 the Provisional IRA torpedoed parts of Belfast in a coordinated bomb attack. That evening footage of human remains being shovelled into clear plastic bags was broadcast on colour televisions across the city. Members of the IRA were divided – some felt that it had been a ‘fuck-up’ while others thought it would ‘harden the bastards up’. The loyalist or Protestant ‘backlash’ – a term which had been used by newspapers of all hues to describe the fomenting anger within communities such as the Shankill and Lower Newtownards Road – was in full swing.

For a small number of loyalists the hot and febrile atmosphere gave them license to go full tilt toward the worst excesses of sectarian violence.

Standing at the corner of Yarrow Street and the Crumlin Road bathed in winter sunshine on this beautiful January afternoon I look along the zebra crossing connecting Yarrow Street to Silvio Street. Beside the top of Silvio Street stands the imposing and magnificent St Mary’s Church of Ireland – a Gothic style high Victorian Church with an enormous central tower designed by London architect William Slater and built from Mourne granite and sandstone in 1868. I then look up at the street sign to my right. ‘Yarrow Street’. There is a newer sign with black text on a white background but beneath it is the white, bold text on a severe black canvass with the old-fashioned abbreviation of street – the uppercase S and lowercase t. When I see these old Belfast street signs I am immediately reminded of news reports from the 1970s. Of journeys unfinished. Lives unfulfilled.

At around 1.30 a.m. on 22 July 1972 Francis Arthurs and his girlfriend were in a taxi travelling up the Crumlin Road from the Engineers Club in Corporation Street where they had been since 10.00 p.m. They were heading back to Arthurs’ house in the Ardoyne when their taxi was stopped. The driver recalled: ‘… I drove up the Crumlin Road. When I got to about St Mary’s Church I was stopped by a number of men.’ Arthurs’ girlfriend later told an inquest:

After reporting Arthurs’ abduction at Glenravel Street the taxi driver, frustrated by the RUC’s apparent lack of action, took Arthurs’ girlfriend to Springfield Road police station where calls were made to the local hospitals. Arthurs’ girlfriend then walked almost two miles to his house at Fallswater Street to see if he had returned home. Finding the house empty she walked two miles again through the darkened streets, back to Springfield Road police station before walking down the Falls Road into the city centre and then back up the Oldpark Road toward her home. If she had turned to look city-wards while she walked she would have seen the sun beginning to creep above the shipyard and the city hall.

At 5.30 a.m. a police constable on patrol in the Oldpark area made a grim discovery:

You’ll see the horrors of a faraway place,

Meet the architects of law face to face.

See mass murder on a scale you’ve never seen,

And all the ones who try hard to succeed.

This is the way, step inside.

This is the way, step inside.

– Joy Division / Atrocity Exhibition [1979]

The following month attention began to be drawn towards this small section of the Crumlin Road where I stood when a man by the name of Thomas Madden was found dead almost three weeks after Arthurs was killed. At the inquest into Madden’s death a Sergeant of the RUC stationed at Oldpark recalled how he came to discover the dead man:

In memory of Tom Madden, R.I.P.

|

| Under the floodlights of Solitude, where I grew up (Gareth Mulvenna, 2021) |

This is a brain-dump … a mixture of personal experience, personal feeling and catharsis. And a bit of walking history. Apologies for the mixed up nature of it, but it just emerged [along with a bit of old biographical writing mixed in] on the back of a long walk on Friday.

Memories Not of My Own

In the midst of the escalating violence, people in Northern Ireland got on with their daily lives; they had to. In the evenings blood would trickle down cast-iron street drains and into the sewers. In parts of North Belfast, the night air would often be punctuated by the sound of gunfire which could be heard for hours on end.

My parents, who lived with my mother’s family at 78 Deerpark Road, off Alliance Avenue, between 1970 and 1975, recall the many times when they expected to wake up in the morning and find bodies strewn across the streets in their hundreds. Often, nobody at all had been killed or injured; but the sound of opposing factions taking pot-shots at each other sound-tracked many a North Belfast evening during this period.

Each morning my parents got up and went to work. My father was an accountant from the South East Antrim port town of Larne and my mother was a primary school teacher who taught infants at St Catherine’s on the Falls Road, opposite the Royal Victoria Hospital. In July 1972 my mother was eight months pregnant with my older brother. The summer of 1972 was a particularly anxious time to live in North Belfast. The Provisional IRA was intensifying its bombing campaign and ordinary Catholics were increasingly having to ‘pick up the tab’ as loyalist paramilitaries began a ferocious backlash against the community they felt was protecting and giving succour to the terrorists responsible for blowing up the city.

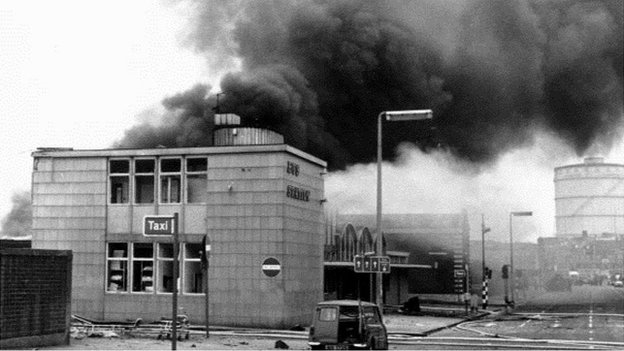

At the time my aunt lived in Dunblane Avenue near the top of the Oldpark Road. On 21 July 1972 my mother and was at my aunt’s house when in the afternoon they suddenly began to hear explosions. There was nothing extraordinary about that. Like gunfire, bombs were part of the symphony to which people in Belfast lived their lives in 1972. However, as the frequency of the explosions became more rapid, my mother and my aunt went to the attic to see what was going on. The upper Oldpark Road gives a good panoramic view of Belfast city centre, the shipyards further to the east and the town of Holywood on the far side of Belfast Lough. What my mother and my aunt saw were massive plumes of smoke agitating the blue and cloudless summer sky. The bombings of that afternoon, perpetrated by ‘D’ Company of the Provisional IRA, would lead to it becoming known as ‘Bloody Friday’ in the ever-expanding Troubles lexicon.

At the time my aunt lived in Dunblane Avenue near the top of the Oldpark Road. On 21 July 1972 my mother and was at my aunt’s house when in the afternoon they suddenly began to hear explosions. There was nothing extraordinary about that. Like gunfire, bombs were part of the symphony to which people in Belfast lived their lives in 1972. However, as the frequency of the explosions became more rapid, my mother and my aunt went to the attic to see what was going on. The upper Oldpark Road gives a good panoramic view of Belfast city centre, the shipyards further to the east and the town of Holywood on the far side of Belfast Lough. What my mother and my aunt saw were massive plumes of smoke agitating the blue and cloudless summer sky. The bombings of that afternoon, perpetrated by ‘D’ Company of the Provisional IRA, would lead to it becoming known as ‘Bloody Friday’ in the ever-expanding Troubles lexicon.

|

Oxford Street bus station on Bloody Friday, 21 July 1972 (Source unknown) |

At the time, my mother and my aunt were involved with the Alliance Party which had been formed two years earlier in the hope of creating a middle-ground in the province. Across the river Lagan in the upstairs lounge of Clancy’s Tavern at the bottom of the Albertbridge Road, a young man from nearby Chamberlain Street named David Ervine was also watching the smoke rising into the Belfast city centre sky. There and then he would decide to get ‘off the fence’ and join the Ulster Volunteer Force in East Belfast, considering that ‘the best means of defence was attack’. He was just one of many young men and women who, when faced with ‘critical incidents’ that were perceived to be an attack on their community in the 1970s, joined either the republican or loyalist paramilitaries. Others would join the Royal Ulster Constabulary, Ulster Defence Regiment or British Army.

In the hours that followed the Bloody Friday bombings, fear stalked the streets. Catholics expected reprisals, some of which would prove to be brutal. At my parents’ home on the Deerpark Road the feeling was no different. At 10 p.m., gunmen shot their neighbour Joseph Rosato a terrazzo fitter who lived at no. 103 dead. It is thought that they were looking for his son and accidentally killed Mr Rosato in the mistaken belief that they had landed on their quarry. Later on, as the evening turned to night there was a loud knock at the door. My grandfather, a tall and strong man in his 70s who had lived through the 1930s Troubles, as well as two world wars, suddenly stiffened with fear. My mother ushered him into a small side room where he hid behind the door. As seconds passed, which undoubtedly felt like hours, my father paused, before asking ‘Who’s there?’ The response came from a reassuringly familiar voice – Oswald Jamison, a friend from the Alliance Party. When he stepped inside, he realised the grave error he had made, and apologised profusely to my heavily pregnant mother and her father.

My mother was increasingly concerned about the impact that the toxic security situation would have on her ability to gain safe passage to the hospital to give birth. Soldiers were frequently to be found in the front gardens of houses in the area, with camouflage paint on their faces. The local corporal approached my mother and offered a V.I.P. journey to the Royal in an army pig. The gesture was a generous one, and was positively received, but politely declined. Going to the Royal in an army personnel carrier in 1972 was probably more dangerous than walking the streets of North and West Belfast on foot after dark.

Darkness … always the darkness.

The darkened streets of 1970s Belfast were ominous arteries which seemed to consume people on an almost nightly basis. Not so ominous, however, that they could deter my mother, her two sisters and my grandmother from having their weekly Thursday night dinner and catch-up at the Four Winds bar and grill in East Belfast. It was after one of these sorties across town that the four of them found themselves stranded in the republican Markets area close to the city centre. Sitting in a Volkswagen Beetle with a punctured tyre after dark and not a sinner about wasn’t an ideal situation for anyone to be in in 1970s Belfast, even less so if you were four women in an unfamiliar part of town. According to my mother, after only a few minutes of living with this quandary the car was suddenly lifted off the ground as local men who had emerged from the darkness set to work on changing the tyre. With a thud and a bounce as the car was placed back on all fours, they were ushered on their way out of the Markets and were homeward bound.

Then there was ‘Tommy the milkman’. This story is sketchier but serves to further illustrate the interface between normality and surrealism in 1970s Northern Ireland. When my parents and my 3-year-old brother moved to the Cliftonville Road in 1976 they were joined by my mother’s parents. The local milkman, ‘Tommy’, was apparently a friendly chap from the Ardoyne who chatted away to my granny and she would often invite him in for a cup of tea and a slice of homemade soda bread.

In the hours that followed the Bloody Friday bombings, fear stalked the streets. Catholics expected reprisals, some of which would prove to be brutal. At my parents’ home on the Deerpark Road the feeling was no different. At 10 p.m., gunmen shot their neighbour Joseph Rosato a terrazzo fitter who lived at no. 103 dead. It is thought that they were looking for his son and accidentally killed Mr Rosato in the mistaken belief that they had landed on their quarry. Later on, as the evening turned to night there was a loud knock at the door. My grandfather, a tall and strong man in his 70s who had lived through the 1930s Troubles, as well as two world wars, suddenly stiffened with fear. My mother ushered him into a small side room where he hid behind the door. As seconds passed, which undoubtedly felt like hours, my father paused, before asking ‘Who’s there?’ The response came from a reassuringly familiar voice – Oswald Jamison, a friend from the Alliance Party. When he stepped inside, he realised the grave error he had made, and apologised profusely to my heavily pregnant mother and her father.

My mother was increasingly concerned about the impact that the toxic security situation would have on her ability to gain safe passage to the hospital to give birth. Soldiers were frequently to be found in the front gardens of houses in the area, with camouflage paint on their faces. The local corporal approached my mother and offered a V.I.P. journey to the Royal in an army pig. The gesture was a generous one, and was positively received, but politely declined. Going to the Royal in an army personnel carrier in 1972 was probably more dangerous than walking the streets of North and West Belfast on foot after dark.

Darkness … always the darkness.

The darkened streets of 1970s Belfast were ominous arteries which seemed to consume people on an almost nightly basis. Not so ominous, however, that they could deter my mother, her two sisters and my grandmother from having their weekly Thursday night dinner and catch-up at the Four Winds bar and grill in East Belfast. It was after one of these sorties across town that the four of them found themselves stranded in the republican Markets area close to the city centre. Sitting in a Volkswagen Beetle with a punctured tyre after dark and not a sinner about wasn’t an ideal situation for anyone to be in in 1970s Belfast, even less so if you were four women in an unfamiliar part of town. According to my mother, after only a few minutes of living with this quandary the car was suddenly lifted off the ground as local men who had emerged from the darkness set to work on changing the tyre. With a thud and a bounce as the car was placed back on all fours, they were ushered on their way out of the Markets and were homeward bound.

Then there was ‘Tommy the milkman’. This story is sketchier but serves to further illustrate the interface between normality and surrealism in 1970s Northern Ireland. When my parents and my 3-year-old brother moved to the Cliftonville Road in 1976 they were joined by my mother’s parents. The local milkman, ‘Tommy’, was apparently a friendly chap from the Ardoyne who chatted away to my granny and she would often invite him in for a cup of tea and a slice of homemade soda bread.

Sometime in the 1970s ‘Tommy’ was arrested and imprisoned, and it came out that he was in fact a “…a quartermaster or something in the Provos”. My grandmother felt totally hoodwinked and her upset was magnified by the fact that she thought people would think less of her for having ‘consorted with a terrorist’. She was born and brought up as Church of Ireland and converted to Catholicism when she married my grandfather, a printer in the Irish News.

In the late 1960s my grandmother was an avid supporter of the Civil Rights movement whereas my grandfather, a man with his ear to the ground, was more cautious. In the 1980s my grandmother was in Belfast city centre, doing some shopping, when she was suddenly approached on a crowded thoroughfare by the recently-released ‘Tommy’. “Ach, Mrs McNally, it’s great to see you, give us a hug!” “Away with you Tommy, you’re a bad man”. A sense of betrayal still lingered in this kind-hearted woman who had lived, as a girl and then a woman, through some of the bloodiest events of the twentieth-century. She needn’t have felt so bad. I’m sure plenty of people had similar experiences. At the end of the day, ‘behind the mask’ republican and loyalist paramilitaries were ordinary people as well.

Walking Among the Dead

I walked through the city limits

(Someone talked me in to try to do it) Attracted by some force within it (Had to close my eyes to get close to it) Around a corner where a prophet lay

(Saw the place where she had a room to stay) A wire fence where the children play

(Saw the bed where the body lay) And I was looking for a friend of mine

(And I had no time to waste) Yeah, looking for some friends of mine

– Joy Division / Interzone [1979]

A couple of years ago when I was talking to Henry McDonald about his novel Two Souls I commented that the soundtrack to the protagonist’s experiences in late 1970s Belfast – Joy Division and ‘Berlin-era’ David Bowie among others – were exactly the same musical references which marked my awakening some twenty years later about the realities of the part of the city in which I lived. I was fortunate to be shielded from the worst of the violence in North Belfast, but as I began to develop my own consciousness about Belfast and its bloody history I was also in the midst of discovering music from the 1970s which I had never heard before. Of course, I knew songs such as “Heroes”, but nothing had prepared me for the Damascene experience of hearing tracks such as ‘Sense of Doubt’, ‘V-2 Schneider’ and ‘A New Career In A New Town’ from Bowie’s two 1977 albums “Heroes” and Low.

Walking Among the Dead

I walked through the city limits

(Someone talked me in to try to do it) Attracted by some force within it (Had to close my eyes to get close to it) Around a corner where a prophet lay

(Saw the place where she had a room to stay) A wire fence where the children play

(Saw the bed where the body lay) And I was looking for a friend of mine

(And I had no time to waste) Yeah, looking for some friends of mine

– Joy Division / Interzone [1979]

A couple of years ago when I was talking to Henry McDonald about his novel Two Souls I commented that the soundtrack to the protagonist’s experiences in late 1970s Belfast – Joy Division and ‘Berlin-era’ David Bowie among others – were exactly the same musical references which marked my awakening some twenty years later about the realities of the part of the city in which I lived. I was fortunate to be shielded from the worst of the violence in North Belfast, but as I began to develop my own consciousness about Belfast and its bloody history I was also in the midst of discovering music from the 1970s which I had never heard before. Of course, I knew songs such as “Heroes”, but nothing had prepared me for the Damascene experience of hearing tracks such as ‘Sense of Doubt’, ‘V-2 Schneider’ and ‘A New Career In A New Town’ from Bowie’s two 1977 albums “Heroes” and Low.

Then came Joy Division. Ian Curtis’s lyrics – his visions – were easily transferable from the urban inner-city landscapes of grim post-war Greater Manchester where, like Belfast, the Luftwaffe and redevelopment had left large swathes of abandoned and isolated land in the midst of otherwise densely built-up neighbourhoods. In Belfast these wastelands – often quite literally ‘no-man’s land’ – came to be haunting grounds which the casualties of sectarian violence still seem to restlessly inhabit.

Interzone, referenced above, with its allusion to walking through the ‘city limits’ always popped into my head as a 17-year-old when I read about the poor craters who had the misfortune to be walking home with a few drinks inside them when they were snatched off the streets around Belfast’s ‘murder mile’ in the mid to late 1970s by the Shankill Butchers.

Having moved back to North Belfast in recent months and ruminating on the lives and deaths of Sammy and Anthony McCleave, I decided to try to emotionally engage with and better understand some of the more obscure and frightening aspects of the early Troubles by treading the physical landscape. Here I have encountered both the streets of my early childhood and those which were often passing references in soon to be forgotten newspaper articles about the violent deaths of innocents. I have also tried to record these walks by means of photography. It is startling how little some of the streets have changed from my childhood and the old, grainy archive footage from the Troubles period.

In early January 2021 I walked around the streets near Solitude where I grew up. I tried and failed to write anything coherent about that experience, but I will revisit it once I’ve fully absorbed its impact on me. Yesterday (22 January 2021) I decided to walk to the top of my street and along the Antrim Road, letting my feet and my memory guide me:

Bottom of the Cavehill Road > Antrim Road > Carlisle Circus > Crumlin Road > Hopewell Avenue > Crumlin Road > Oldpark Road > Rosewood Street > Yarrow Street > Crumlin Road > Ardoyne Road > Alliance Avenue > Westland Road > Hughenden Avenue

Walking down the Antrim Road I thought back to the days when as a young man I would recklessly amble along here toward my parents’ home after a night on the town. Drunk, depressed, arrogant of all of the dangers I had read about in the books that filled my bookcase. I knew how dangerous this route was and could still be after dark, but such was my disregard for my own existence that I didn’t care about my own fate. I thought long about the awkward and shy 15-year-old in his Methody uniform, feeling completely out of place among the St Mac’s and St Mary’s boys who I had gone to school with, many of whom no longer talked to me. How could they know that I wasn’t smug or different – I just felt out of place in my new school. When a very small group of the middle-class boys in my year at Methody discovered that I was a ‘taig’ [I’d only ever been called that once before, in Scouts] they liked to subtly bully me in the way that middle-class kids do; putting on a Belfast accent, asking me how it was on the Falls, calling me ‘Ra man’.

‘Fuck do they know about anything’ I thought as my anger typically subsided into sadness and self-loathing. I was so sheltered from the harsh realities of life that I didn’t even realise that I was middle-class, like them. Not that they or their parents would ever have countenanced such a phenomenon. Meanwhile my best friends in school – the ‘three Jamies’ – from Ballygomartin, Woodvale and Silverstream provided relief from the daily discomfort of the early months of 1996 …

… At the same time many afternoons at Methody were spent privately sweating about which bus to get home: the Antrim Road or the Downview. A group of younger lads from round the corner – middle class like myself but rebelling hard against it – had taken an intense dislike to me. I still can’t fathom the exact reason why. They would wait for me in a group of four or five, all wielding Hurley sticks. I managed to evade them every day until (ironically) the summer holidays when they managed to jump me while I was riding my bike at the front of my house. I still remember the tears of frustration and anger and the empty apology later proffered by one of their fathers from behind his Alfa Romeo convertible to my dad.

‘Do you hear that the Basher is dead?’

‘I heard the shots from my house.’

‘What’s that book?’

‘It’s my da’s copy so be sure to give it back.’

June 1997 – news that someone called Basher Bates was shot dead. People on the street were talking about it, saying to beware any black taxis in the area. Returning to school to hear one of the Jamies [Woodvale] telling us in Eason [when it was in Castle Court] that he had heard the shots that killed Basher while he was in his house. A few weeks later a friend of mine – one of the only guys I have retained contact with since my Christian Brothers primary school days – offers me a copy of a book called The Shankill Butchers.

I read it in one night and finish it as the sun comes up. I have to go for a cycle to wash it out of my head. Twenty-four years later it is still stuck to my brain like a toxic glue.

Even now as I write this a playlist throws up ‘Gonna Make You A Star’ by David Essex into my ears.

Interzone, referenced above, with its allusion to walking through the ‘city limits’ always popped into my head as a 17-year-old when I read about the poor craters who had the misfortune to be walking home with a few drinks inside them when they were snatched off the streets around Belfast’s ‘murder mile’ in the mid to late 1970s by the Shankill Butchers.

Having moved back to North Belfast in recent months and ruminating on the lives and deaths of Sammy and Anthony McCleave, I decided to try to emotionally engage with and better understand some of the more obscure and frightening aspects of the early Troubles by treading the physical landscape. Here I have encountered both the streets of my early childhood and those which were often passing references in soon to be forgotten newspaper articles about the violent deaths of innocents. I have also tried to record these walks by means of photography. It is startling how little some of the streets have changed from my childhood and the old, grainy archive footage from the Troubles period.

In early January 2021 I walked around the streets near Solitude where I grew up. I tried and failed to write anything coherent about that experience, but I will revisit it once I’ve fully absorbed its impact on me. Yesterday (22 January 2021) I decided to walk to the top of my street and along the Antrim Road, letting my feet and my memory guide me:

Bottom of the Cavehill Road > Antrim Road > Carlisle Circus > Crumlin Road > Hopewell Avenue > Crumlin Road > Oldpark Road > Rosewood Street > Yarrow Street > Crumlin Road > Ardoyne Road > Alliance Avenue > Westland Road > Hughenden Avenue

Walking down the Antrim Road I thought back to the days when as a young man I would recklessly amble along here toward my parents’ home after a night on the town. Drunk, depressed, arrogant of all of the dangers I had read about in the books that filled my bookcase. I knew how dangerous this route was and could still be after dark, but such was my disregard for my own existence that I didn’t care about my own fate. I thought long about the awkward and shy 15-year-old in his Methody uniform, feeling completely out of place among the St Mac’s and St Mary’s boys who I had gone to school with, many of whom no longer talked to me. How could they know that I wasn’t smug or different – I just felt out of place in my new school. When a very small group of the middle-class boys in my year at Methody discovered that I was a ‘taig’ [I’d only ever been called that once before, in Scouts] they liked to subtly bully me in the way that middle-class kids do; putting on a Belfast accent, asking me how it was on the Falls, calling me ‘Ra man’.

‘Fuck do they know about anything’ I thought as my anger typically subsided into sadness and self-loathing. I was so sheltered from the harsh realities of life that I didn’t even realise that I was middle-class, like them. Not that they or their parents would ever have countenanced such a phenomenon. Meanwhile my best friends in school – the ‘three Jamies’ – from Ballygomartin, Woodvale and Silverstream provided relief from the daily discomfort of the early months of 1996 …

… At the same time many afternoons at Methody were spent privately sweating about which bus to get home: the Antrim Road or the Downview. A group of younger lads from round the corner – middle class like myself but rebelling hard against it – had taken an intense dislike to me. I still can’t fathom the exact reason why. They would wait for me in a group of four or five, all wielding Hurley sticks. I managed to evade them every day until (ironically) the summer holidays when they managed to jump me while I was riding my bike at the front of my house. I still remember the tears of frustration and anger and the empty apology later proffered by one of their fathers from behind his Alfa Romeo convertible to my dad.

‘Do you hear that the Basher is dead?’

‘I heard the shots from my house.’

‘What’s that book?’

‘It’s my da’s copy so be sure to give it back.’

June 1997 – news that someone called Basher Bates was shot dead. People on the street were talking about it, saying to beware any black taxis in the area. Returning to school to hear one of the Jamies [Woodvale] telling us in Eason [when it was in Castle Court] that he had heard the shots that killed Basher while he was in his house. A few weeks later a friend of mine – one of the only guys I have retained contact with since my Christian Brothers primary school days – offers me a copy of a book called The Shankill Butchers.

I read it in one night and finish it as the sun comes up. I have to go for a cycle to wash it out of my head. Twenty-four years later it is still stuck to my brain like a toxic glue.

Even now as I write this a playlist throws up ‘Gonna Make You A Star’ by David Essex into my ears.

Lenny loved David Essex. All the girls loved David Essex, and someone told Lenny he looked like David Essex, so he went out and done his hair like David Essex and started wearing a handkerchief in his top pocket. He fucking loved himself.

The banality of evil – Lenny Murphy checking the mirror to make sure his hair was like David Essex’s and listening to his favourite album, ‘Band on the Run’. The information you collect over the years.

At the bottom of the Antrim Road I turned right onto the Crumlin Road.

I knew what I was looking for, but I was trying to put it off.

I looked up at the Mater Hospital and thought of the terrible pressure on the staff inside – the nurses dutifully tending to people dying from the Covid pandemic, the families marginalised from proper grief. Funerals viewed on YouTube.

At the bottom of the Antrim Road I turned right onto the Crumlin Road.

I knew what I was looking for, but I was trying to put it off.

I looked up at the Mater Hospital and thought of the terrible pressure on the staff inside – the nurses dutifully tending to people dying from the Covid pandemic, the families marginalised from proper grief. Funerals viewed on YouTube.

|

Mater Hospital Crumlin Road (Gareth Mulvenna, 2021) |

I had a good look at Crumlin Road Gaol – the closest thing Belfast has to a government-sanctioned Troubles tourism commodity. With all the renovations of recent years it has become a Disney Land version of real history. The history left by the Troubles can’t be found in Cuffs restaurant or in Folsom Prison Blues tribute nights … it can be better found in the streets nearby or in the forbidding husk of the courthouse across the road.

I walk down Hopewell Avenue and take a couple of photos of the ‘summer of 1969’ mural – the loyalist commemoration of that fateful season that lit the spark of sectarian violence in Belfast. Then there is the refurbished mural in tribute to Stevie McCrea. McCrea, a Red Hand Commando volunteer, was killed by the Irish People’s Liberation Organisation [IPLO] in February 1989 while having a lunchtime drink with friends in the Orange Cross social club, not far from where the mural stands. McCrea was arrested on Hallowe’en 1972 for shooting dead a Catholic teenager, James Kerr, at a garage forecourt on the Lisburn Road. When questioned by police he claimed the dead man was shot because he was a ‘Fenian bastard’, but McCrea’s friends allege that Kerr had been involved in assaulting McCrea’s brother and carving ‘IRA’ onto his skin. According to Lost Lives:

I walk down Hopewell Avenue and take a couple of photos of the ‘summer of 1969’ mural – the loyalist commemoration of that fateful season that lit the spark of sectarian violence in Belfast. Then there is the refurbished mural in tribute to Stevie McCrea. McCrea, a Red Hand Commando volunteer, was killed by the Irish People’s Liberation Organisation [IPLO] in February 1989 while having a lunchtime drink with friends in the Orange Cross social club, not far from where the mural stands. McCrea was arrested on Hallowe’en 1972 for shooting dead a Catholic teenager, James Kerr, at a garage forecourt on the Lisburn Road. When questioned by police he claimed the dead man was shot because he was a ‘Fenian bastard’, but McCrea’s friends allege that Kerr had been involved in assaulting McCrea’s brother and carving ‘IRA’ onto his skin. According to Lost Lives:

The republican publication Belfast Graves refers to him [Kerr] as a ‘comrade’ of IRA man John Rooney. His name, however, does not appear on any republican roll of honour nor does he have a separate entry in Belfast Graves.

Belfast, 1972 … two young men. One dead, the other facing the best years of his life in jail before facing the same fate shortly after his own release as a 36-year-old … Belfast, 1989 …

Back on the Crumlin Road I walked across the road, passing the top of Cliftonpark Avenue – a street with many stories … perhaps for another time.

For now it was time to revisit my old place of work. Oldpark Road Library, where I was employed as a library assistant from October 2003 until May 2004, is now derelict. This period of my life was dreadful. I was depressed almost all the time (though I didn’t realise it at the time – depression was one of those things that happened to someone like Richey Edwards wasn’t it?). I was also acutely aware of the fact that the library had faded from its previous grandeur. With Cairn Lodge Youth Club run into the ground I worked as a librarian issuing Westerns and Mills & Boon to good-natured elderly folk from the Oldpark, Crumlin and Shankill. Well, that was my job … what I didn’t realise was that I was going to have to act up as a youth worker for some of the young lads who used the library as a drop-in centre.

I stood at the front of the library, looking at the steps. Often I would arrive just in time to encounter Wilma eagerly cleaning those steps with a big basin of warm water and bleach. Her warmness juxtaposed starkly with the chemical stench which fixed itself in my nostrils and throat.

|

| Front steps of Oldpark Road Library (Gareth Mulvenna, 2021) |

I remember an old lady from Cambrai Street coming in one day – she was a regular borrower – and ambling up to the issue desk where I was lost in thought about the inevitable end of my first relationship. Tears were stinging my eyes. She said, ‘Don’t worry son, it may never happen.’ It did, that very February evening.

For days, weeks, months tears tripped me. I had to act the big man and pretend it hadn’t got to me as I sought solace in copious amounts of drink and the task of trying to get someone else to be my new girlfriend.

‘Do you have the new Lee Child son?’

Looking for a surrogate for affection, validation, I struck up a friendship with the library security guard, Billy. Billy was a former UDR man from Omagh who lived in Carrick. He was probably about twenty years older than me, but we spent days talking. He had a very macho, bravado attitude to what I was going through and brought me in a bag of FHM magazines one day. He probably thought this would help, but it just intensified my misery. Billy’s father had been an RUC man and was blown up by a 600 lb IRA landmine in August 1981. Apparently his dad and his RUC colleague were found in pieces across nearby fields. Billy told me that his father loved country music, which he hated. He didn’t seem to get on with his dad. We would stand at the front window of the library, chatting while looking across the road to Manor Street.

Whosoever shall call on the name of the Lord shall be saved. Acts 2 v 21.

‘How long do you think it will take Willie John to get across the road today?’, Billy would ask me as we watched one the library’s most infamous visitors make his way from Manor Street, trying to stagger across the road in a drunken stupor. It didn’t matter, because WJ was barred. One day he made it in and proceeded to piss himself in front of the area manager who deftly made herself unavailable while myself and Billy cleaned up and ushered WJ out.

As I walked around the side of the library I peered through the window grilles to have a look at the old staff room behind the issue desk. I recall many days clambering in and out of there to gulp from a large bottle of Lucozade which I had in my bag to raise the energy I had lost from the previous night’s drinking. Drinking to forget. A broken heart. Close to collapse. A list of regrets longer than my arm.

Almost forty-nine years ago this part of the Crumlin Road was an unofficial ‘check-point’ manned by the UDA and other loyalists. Yarrow Street isn’t often mentioned in accounts of the Troubles, but for someone with an intimate knowledge of that period in history it is difficult when walking through this part of town not to cast one’s mind back to the dreadful summer of 1972. On Friday 21 July 1972 the Provisional IRA torpedoed parts of Belfast in a coordinated bomb attack. That evening footage of human remains being shovelled into clear plastic bags was broadcast on colour televisions across the city. Members of the IRA were divided – some felt that it had been a ‘fuck-up’ while others thought it would ‘harden the bastards up’. The loyalist or Protestant ‘backlash’ – a term which had been used by newspapers of all hues to describe the fomenting anger within communities such as the Shankill and Lower Newtownards Road – was in full swing.

For a small number of loyalists the hot and febrile atmosphere gave them license to go full tilt toward the worst excesses of sectarian violence.

Standing at the corner of Yarrow Street and the Crumlin Road bathed in winter sunshine on this beautiful January afternoon I look along the zebra crossing connecting Yarrow Street to Silvio Street. Beside the top of Silvio Street stands the imposing and magnificent St Mary’s Church of Ireland – a Gothic style high Victorian Church with an enormous central tower designed by London architect William Slater and built from Mourne granite and sandstone in 1868. I then look up at the street sign to my right. ‘Yarrow Street’. There is a newer sign with black text on a white background but beneath it is the white, bold text on a severe black canvass with the old-fashioned abbreviation of street – the uppercase S and lowercase t. When I see these old Belfast street signs I am immediately reminded of news reports from the 1970s. Of journeys unfinished. Lives unfulfilled.

We drove up the Crumlin Road and we were stopped at Yarrow Street/Crumlin Road. There were about 10 or 12 U.D.A. men on the road and on the footpath. The taxi door was thrown open from outside. A man said, “Any identification here”. The man and the women who were sitting in the taxi facing Frankie and me, that is to say with their backs to the taxi driver, started to look for something in their pockets to identify themselves. The same man who had asked for identification said “Everybody out”. We all got out onto the street. I was the last to get out and I saw that about four men had Frankie standing with his hands against a shop and his feet spread out. The men were searching him. I said to the men “This is ridiculous that people can’t go home after a night out without getting pulled out of a car.” Nobody paid any attention to me so I got back into the taxi again. After a few minutes Frankie got back into the taxi again. The men asked him where he was going and he said [redacted], that was the first time he was taken out. When Frankie got into the taxi the door was thrown open again and someone said, “Right, out you” to Frankie and he got out again. He did not protest or put up any fight to the men. He was taken by the arms by a number of men who took him round the front of the taxi and across Crumlin Road towards Yarrow Street.

At 5.30 a.m. a police constable on patrol in the Oldpark area made a grim discovery:

I was driving my car along Manor Street in the direction of the Cliftonville Road. As I passed the waste ground at the junction of Liffey Street/Manor Street I saw a Morris Oxford car … parked close to the gable wall of the houses. I saw that the driver’s door was open and the windscreen wiper had been switched on. I walked over to the car and saw the body of a man lying on his back across the rear seat with one foot outside the open rear near side passenger door. There was blood on his face which appeared to have been badly beaten. I felt for a pulse with negative results. I also saw an empty cartridge case lying on top of the body and another one on the floor of the car.

You’ll see the horrors of a faraway place,

Meet the architects of law face to face.

See mass murder on a scale you’ve never seen,

And all the ones who try hard to succeed.

This is the way, step inside.

This is the way, step inside.

– Joy Division / Atrocity Exhibition [1979]

The following month attention began to be drawn towards this small section of the Crumlin Road where I stood when a man by the name of Thomas Madden was found dead almost three weeks after Arthurs was killed. At the inquest into Madden’s death a Sergeant of the RUC stationed at Oldpark recalled how he came to discover the dead man:

At 5.55 a.m. on Sunday, August, 13th, 1972, I was on duty in the local D.M.P. car. I received a communication from Police Control to check out a report that a body was in the doorway of Sloan’s Paper Shop. The Military were present at the shop when I arrived. I saw the body of a male person lying face downwards with his feet up in the air against the door of the shop. There was blood coming from underneath the body and ran onto the footpath. There was an iron gate, approximately 6′ high across the doorway. It was apparent from the shape of the body that it had been dumped over the top of the iron gate. The body appeared to be dead and I called for a doctor to pronounce life extinct. I also arranged for Detectives, S.O.C.O. and [redacted] to be informed. A soldier pointed out what appeared to be a trail caused by something being dragged across the ground. I followed this trail across the Oldpark Road into Baden Powell Street. The trail then led into the entry between Baden Powell Street and Hillview Street. About half-way down the entry I saw false teeth lying on the ground amongst blood and the remnants of what appeared to be a paper bag. I told Constable [redacted] who was with me, to remain with these items and I continued to follow the trail. The trail appeared to end at the rear of [redacted]. I entered the house but could find nothing. I then searched the back yard of [redacted] and I found a shoe which later proved to belong to the dead man. I also found an empty wine bottle in the entry. I handed both the shoe and the empty bottle to Constable [redacted] S.O.C.O., at the scene.

It is often alleged that Thomas Madden was killed by a gang which included Lenny Murphy. While it isn’t clear whether Murphy was involved or not, there is no doubt that whoever was involved in killing Madden was someone who enjoyed using a knife to inflict pain. The trail of blood led to an alleyway near Yarrow Street; only a matter of yards. The house which was searched by the RUC Sergeant was likely less than a two minute walk from where Arthurs had been abducted on 22 July 1972. Arthurs and Madden are two men who relentlessly figure in my thoughts about the early Troubles.

Despite the fact that Yarrow Street and Silvio Street have changed considerably since redevelopment occurred in the 1980s, there continues to be a strong sense of these men’s lives and deaths echoing around the physical remnants of the old area. I have never seen a photograph of Arthurs and only recently found a picture of Thomas Madden. Indeed it was discovering the photograph and more details about Madden’s last days that compelled me to walk here today. I thought about how much Belfast has changed since 1972…since 1998…and then thought about how little things have changed for some. Thomas Madden, a ghost whose face I had tried to conjure for over twenty years. Whose apparent last words, at 4 a.m., as recalled by a woman in the vicinity of Louisa Street were screamed: ‘Kill me. Kill me.’

And it’s four in the morning and once more the dawning

Just woke up the wanting in me

It’s four in the morning and once more the dawning

Just woke up the wanting in me

– Faron Young / It’s Four in the Morning [1971]

Many of the streets which bore witness to the escalating violence of the early 1970s in the Oldpark area no longer exist. In instances where they remain they are unrecognisable from the once tightly-packed terraced housing which characterised industrial Belfast. Almost a year after the murder of Thomas Madden the BBC’s Scene Around Six news programme dispatched reporter Brian Walker to the area to report on the dramatic effect that the violence of 1971-72 had had on the district. Accompanying him was the community relations officer for the area, Brendan Henry. Henry, a native of Cookstown, had left his post as a primary school teacher in 1970 ‘to follow a career in youth and community work, putting himself at the heart of efforts to forge cross-community links at time when the troubles were starting to ignite.’ [Irish News obit. 28 December 2013] During the report which was filmed in some of the most volatile parts of the Oldpark – Heathfield Road, Louisa Street, Glenpark Street – Henry balefully summed up how the area had rapidly deteriorated in a manner which encapsulated the broader problems in the country:

Brian Walker:

As frontiers collapsed the human condition inevitably led to conflict. People like Thomas Madden were swept up by the anger and hatred created by the flux. As I thought of the whole area where I stood and how it had changed substantially I was reminded that a 23-year-old with a broken heart is not the worst thing to be. Thomas Madden had reason to be devastated. His brother, Hugh, had been shot dead by the UDA eight weeks before he himself was killed. In the weeks between his brother’s murder and his own death Thomas appeared distracted and agitated. His landlady, Mary McGillen, also his friend and confidant, later told an Irish newspaper:

At the inquest into Madden’s murder a member of staff at one of his favourite pubs, the Meeting of the Waters in Manor Street, recalled:

In fact Thomas was supposed to have started his shift at Ewarts at 6 p.m. but even after he left the Meeting of the Waters at 8.45 p.m.he didn’t turn up. Mrs McGillen gave further insight into Thomas’s state of mind and what had happened to him in the previous weeks:

When he was captured by his killers Thomas Madden was brought to an unknown location in the vicinity of Louisa Street. He was stripped and suspended by a rope from a wooden beam. One of his assailants chipped at his flesh with a knife like a sculptor working at marble. He was stabbed 147 times. A local woman later told the coroner:

_

The ghosts of those bloody months in the summer of 1972 continue to hang over Belfast. Despite the huge Waterfront redevelopment around the Oxford Street and East Bridge Street area it is difficult not to be reminded of the images of the senseless violence of Bloody Friday. The further out of the city centre you walk the clearer and closer the past becomes. Some of the streets around the Oldpark and Crumlin roads are long gone, the scars of violence long demolished.

The occult and restless past is still there, however.

A walk around Belfast will bring anyone with a modicum of knowledge about the Troubles into contact with the unsettled dead.

And it’s four in the morning and once more the dawning

Just woke up the wanting in me

It’s four in the morning and once more the dawning

Just woke up the wanting in me

– Faron Young / It’s Four in the Morning [1971]

Many of the streets which bore witness to the escalating violence of the early 1970s in the Oldpark area no longer exist. In instances where they remain they are unrecognisable from the once tightly-packed terraced housing which characterised industrial Belfast. Almost a year after the murder of Thomas Madden the BBC’s Scene Around Six news programme dispatched reporter Brian Walker to the area to report on the dramatic effect that the violence of 1971-72 had had on the district. Accompanying him was the community relations officer for the area, Brendan Henry. Henry, a native of Cookstown, had left his post as a primary school teacher in 1970 ‘to follow a career in youth and community work, putting himself at the heart of efforts to forge cross-community links at time when the troubles were starting to ignite.’ [Irish News obit. 28 December 2013] During the report which was filmed in some of the most volatile parts of the Oldpark – Heathfield Road, Louisa Street, Glenpark Street – Henry balefully summed up how the area had rapidly deteriorated in a manner which encapsulated the broader problems in the country:

It is a cock-pit, and a microcosm of all the troubles in Northern Ireland … This being an interface area there’s a tremendous amount of shooting across from behind us and from in front of us […] [the residents] moved out and the houses became derelict, and the kids wrecked them. This is the Louisa Street end of the Oldpark, the interface area between the Bone and Louisa Street. As we come up here [Glenpark Street], you can see on your left one of the most famous riot spots – the gap – we had rioting there in the 1920s, the 1930s and the 1960s. Now as a result of the rioting here the army put a post there…they’ve another one at the top of the street…which increased the violence to a certain extent causing these people here, right along this street, to move out. Again, we go back to the old thing – just a few of the older people and maybe one or two young couples living here.

Brian Walker:

Yes, but if you listen to the UDA and listen to all the talk over the years, Louisa Street was a proud frontier that people were prepared to defend and yet they’ve had to move out like everywhere else. [Source: BBC Rewind]

Tom was a simple man. He had the mind of a child – he had never grown up. He worked in Ewarts Mill on the Crumlin Road in the looming section and sometimes earned some extra money by doubling as a night watch-man.

He was always a punctual person, but three weeks before his murder he came home late one night and I asked him what had happened. He was white-faced and terrified. He said he had been picked up by the U.D.A. at Yarrow Street and interrogated.

The U.D.A. men asked him about the murder of his brother […] They asked him if he was looking for revenge and if he had any clue about who killed his brother. He said he hadn’t and was leaving it to the police. [Evening Herald, 15 August 1972]

The U.D.A. men took a holy medal and another religious object from him as well as a packet of cigarettes, and then let him go. The experience was one of the things which made him a very frightened man. On the night before his murder he didn’t want to go to work. He told me he was afraid to go outside the door because he was certain he would be killed. He said: ‘I know they’re after me.’

At the inquest into Madden’s murder a member of staff at one of his favourite pubs, the Meeting of the Waters in Manor Street, recalled:

On Saturday the 12th August 1972, I was working in the bar of The Meeting of the Waters. I recall Tommy Madden calling here about 6.30 p.m. The boss, [redacted] went for his tea about half past seven and he had been talking to Tommy before he left. Tommy had been watching television and left here just before nine, probably about 8.45 p.m. as he said that would leave him up to his work about nine. He always worked on Saturday night as a gate man at William Ewarts on the Crumlin Road. I know he had gone down and along Century Street and up the Crumlin Road in the past but in recent times because of the killings the customers had advised him to go up through the ‘Bone’ and across the Brickfields as it was safer. He was also known to go across Louisa Street.

In fact Thomas was supposed to have started his shift at Ewarts at 6 p.m. but even after he left the Meeting of the Waters at 8.45 p.m.he didn’t turn up. Mrs McGillen gave further insight into Thomas’s state of mind and what had happened to him in the previous weeks:

The interrogation by the U.D.A. was not the thing which produced a noticeable change in him, that happened some time earlier. During the Twelfth of July celebrations he disappeared for three days. Members of his family and friends searched for him everywhere but he couldn’t be located. When he did come back he was a changed man. He said he had been in Ardoyne, but as far as I know no one ever saw him there at any time.

It is thought that during the three days he was with the U.V.F. – but that is something we shall never know for sure. What we do know is that just three weeks before he died he was definitely in the hands of the U.D.A.

When he was captured by his killers Thomas Madden was brought to an unknown location in the vicinity of Louisa Street. He was stripped and suspended by a rope from a wooden beam. One of his assailants chipped at his flesh with a knife like a sculptor working at marble. He was stabbed 147 times. A local woman later told the coroner:

On Saturday night August 12th. I was at the Disco in the band hut in Butler Street along with [redacted] who lives in [redacted]. I left the Disco at 3.30 am on Sunday morning after tidying up. We went to [redacted] for a cup of tea and then I came home. My two daughters were at the disco and had left earlier. When I got home the younger daughter was at home but the elder was not at home. We waited until about 4.45 am and my young daughter and I went to see where my other daughter was. We looked round the corners and then walked up the Oldpark Road on the left going from the city. It was daylight and I saw what looked like a bundle of clothes lying in the doorway of Sloan’s shop on the right hand side of the road. I didn’t know what it was and I was afraid to go over so I went up to the soldiers at Louisa Street and reported it to them.

|

The ghosts of those bloody months in the summer of 1972 continue to hang over Belfast. Despite the huge Waterfront redevelopment around the Oxford Street and East Bridge Street area it is difficult not to be reminded of the images of the senseless violence of Bloody Friday. The further out of the city centre you walk the clearer and closer the past becomes. Some of the streets around the Oldpark and Crumlin roads are long gone, the scars of violence long demolished.

The occult and restless past is still there, however.

A walk around Belfast will bring anyone with a modicum of knowledge about the Troubles into contact with the unsettled dead.

In memory of Tom Madden, R.I.P.

⏩ Gareth Mulvenna is an historian of loyalism. Follow on Twitter @gmulvenna1980.

A chilling piece Gareth - I think everybody of an age remembers the death of Thomas Madden

ReplyDeleteThe terror which this piece evokes jumps off the text to seize the reader in its grip, Gareth.

ReplyDeleteWe can only hope that such inhumanity and depravity is never reenacted on those streets.