China is “focusing its recovery on high-carbon energy and infrastructure, as it did after the 2008-09 global financial crisis”, says Carbon Brief, who analysed the spending plans. Dozens of new coal-fired power stations and climate-trashing coal-to-chemicals plants are among the key items.

|

| One of China’s vanity projects: a puffer fish statue in Jiangsu province, which provoked social media outrage when it was unveiled |

The plans make a mockery of Chinese premier Xi Jinping’s claim to the United Nations in September to be aiming for “carbon neutrality before 2060”.

This chasm between words and actions makes Xi a “climate arsonist” still more dangerous than Donald Trump, Richard Smith, a US-based China researcher, writes in a recent article. Smith fears that Xi is “abandoning the transition to renewables”.

In a book published last year, China’s Engine of Environmental Collapse, Smith argues that China’s combination of bureaucratic dictatorship and capitalism has exacerbated its climate impact, and that growth-centred economic policies are incompatible with Xi’s claims to want to protect the natural world.

Smith, writing from a Marxist standpoint, suggests ways that China could “grab the emergency brake” to help forestall climate disasters, and considers prospects for revolutionary change.

In this post I offer some thoughts on these issues; in a linked post I compare Smith’s approach with others on the “left”.

Download both posts as a PDF here

1: Xi Jinping’s growth-focused policies are leading China, and the world, towards disaster

Xi, addressing the UN in September last year, said that the 2015 Paris agreement “charts the course for the world to transition to green and low-carbon development”. It should be honoured; China would adopt “more vigorous policies and measures”, aiming to peak carbon dioxide emissions before 2030 and achieve carbon neutrality by 2060.

The pledge “raised more questions than it answered”, Smith writes. What did “carbon neutrality” mean? How could China keep increasing emissions for another decade, and throw its “immense coal-fired dreadnought into reverse” to force emissions down to zero?

The reality, Smith argues, is that Xi can not meet his own climate targets, because the Chinese elite’s priority since Mao Zedong’s day has been to compete with, and protect itself from, the US and other powers by expanding the economy. Xi therefore “has no choice but to maximise the growth of the very industries that are driving China’s emissions off the charts, including coal-fired electricity generation, even if this accelerates global warming, dooming China and the planet too”.

There are two obvious reasons to take Smith’s warnings seriously.

First, Xi’s doublethink is in line with that of UK, European and US Democratic party politicians who swear by the Paris agreement. As UN officials made clear even before the Paris conference, it would not reach a deal sufficient to stave off dangerous climate change. And it did not. Climate Action Tracker monitors the gulf between deeds and words. Xi is a big part of a bigger problem.

Second, Smith is hardly alone in highlighting the yawning chasm between Xi’s words and the ongoing policy support for coal. Mainstream commentators and NGOs do too.

China’s failure to focus post-Covid investments on low-carbon energy indicates “general agreement among the political elites that policy goals other than the low-carbon transition were more important, notably short-term economic growth, employment and social stability”, Philip Andrews-Speed, a researcher of China’s energy system, wrote.

Researchers at Boston University pointed out that state-owned Chinese banks are now the leading international lenders to coal projects elsewhere.

Even Zou Ji, a former state climate official and now president of Energy Foundation China, an NGO, said: “Don’t add new capacity, as that will lock in emissions and create a vicious circle. Once the capacity is there, it will be used, and prevent reductions in coal-fired power.” Technological advances “are removing the justifications for building new coal power”, he added.

The authorities are not listening. Carbon emissions from both electricity generation and steel-making have bounced back from the Covid lockdown and are hitting new records.

2: The combination of bureaucratic rule and capitalism has exacerbated the problem

However much Xi’s empty promises on climate resemble Angela Merkel’s or Boris Johnson’s, the disconnect between word and deed works differently in China. other states have ceded to the markets. While Johnson’s inadequate climate targets disappear in a cloud of rhetoric and broken “market mechanisms”, Xi’s get caught in the crossfire between his own economic policy priorities on one hand and bureaucratic interests in China’s provinces and industries on the other.

Take investment in coal production and coal-fired electricity generation. “Distorted incentives favour coal”, Max Dupuy of the Regulatory Incentives Project explains. Provincial and local officials use their authority “to encourage heavy industrial investments in their jurisdictions”.

Under a system that some describe as a “GDP competition” to promote economic growth, officials realise that an easy way to boost their statistics is “to engineer finance for large industrial and infrastructure investment”. This, combined with preferential credit to heavy industry, has “contributed to overinvestment in heavy industry and has been a major part of the story of coal investment in China”.

This dynamic between national and local bureaucrats is discussed in greater detail, and put into international and historical context, in Smith’s book, China’s Engine of Environmental Collapse.

The coal-driven boom was fired up in the first place by exporting manufactured goods to rich countries, following China’s accession to the World Trade Organisation (WTO) in 2001. More recently, government policy has focused on reproducing bloated, western-style consumer markets in China itself, Smith argues.

In other words, the unique relationship between China’s bureaucratic ruling elite and capitalism, both internationally and within China, has driven forward the biggest coal-based industrial expansion drive in world history. And makes it harder to shift away from it.

Smith’s article identifies three “hypergrowth drivers” in the Chinese elite’s approach: (i) determination to “win the economic and arms race with the US”; (ii) the need to maximise employment; and (iii) the need to maximise consumption and consumerism. Smith writes:

As a state-based communist ruling class in a world dominated by more advanced and powerful capitalist powers, Xi, like Mao and Deng before him, understands that China must “catch up and overtake the US”. That’s the only guarantee that it will not be overwhelmed by global capitalist imperialism. The way to do that is to build a relatively self-sufficient high-tech superpower economy shielded from Western takeover.

Analysing the relationship between the Chinese elite and capitalism is not simple. I won’t try it in a blog post, and I don’t think Smith has finished the job either. But by probing the causal role of that relationship in China’s horrifying volume of greenhouse gas emissions, Smith is pointing us in the right direction.

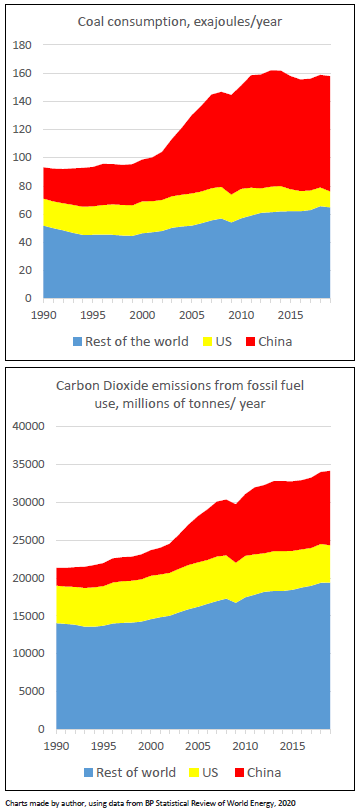

I will add to the conversation the two graphs, showing China’s, and the USA’s, share of global greenhouse gas emissions, and coal production, over the last thirty years. Quantity turns into quality. The sheer scale of China’s coal-fuelled boom has been one of the major factors that has exacerbated the climate crisis.

The Chinese leadership pressed ahead with coal-based expansion, notwithstanding the science of global warming, which was already clear in the late 1980s. Deng Yingtao, an economist and government adviser, explained in a book published in 1991 the vital need to take a different road. (I published an account of his work here.) But China’s elite ignored such advice. This is a factor in the climate and ecological crisis we face now.

3: The Chinese government’s ruinous approach can not be described as a development policy. It prioritised, first, supplying manufactured goods to the world market, and then, creating a market for consumer goods in China.

In the half century since 1970, China’s economic policies have delivered gigantic improvements to the material living standards of its citizens. Levels of nutrition, income, literacy, health provision and electricity supply have risen for hundreds of millions of people.

Anyone who thinks tackling climate change has to go hand-in-hand with fighting for social justice welcomes such changes unequivocally.

But that is not the whole story. As industry grew in the 1990s, and that growth accelerated in the 2000s, as hundreds of millions of people moved to towns and new industrial zones and economic sectors were opened to private capital, much uglier aspects of economic expansion came to the foreground.

In his book, Richard Smith argues that China’s exports to the world market gained competitive advantage by (i) the low cost of “semi-coerced ultra-cheap workers to power light manufacturing”, (ii) “contempt for, and lack of spending on, environmental protection”, and (iii) the state’s capacity to work with investors to build physical infrastructure. The authoritarian political system helped (pages 2-4).

|

| An open-pit coal mine in China |

By the time of China’s twelfth five-year plan (2006-2010), Smith writes, the “blind growth” had turned into an orgy of overproduction, fuelled by relatively cheap labour and eco-insanity. He lists the excesses (pages 24-43), such as a car-building (and owning) craze that brought cities to a standstill with traffic jams, and, in the countryside, the construction of roads and rail links that no-one uses.

While in some regions migrant workers are packed in dormitories like sardines, ghost cities of empty skyscrapers have gone up elsewhere in property markets dominated by speculators. One example: Caofeidian on the Bohai Sea (cost $100 billion), which was to have been “the world’s first fully-realised eco-city”; planned for 1 million people, only a few thousand ever moved in. Vanity building projects abound, from mock Versailles palaces to an $11 million, 2300-tonne tower shaped like a puffer fish in Jiangsu province.

To pay for all this: the world’s worst record on industrial safety and environmental standards.

Smith argues (pages 126-153) that, amid this frenzy of scatter-gun investment, the command system of management and constraints on markets combine to incentivise corruption among the 90 million members of the Communist Party. The leadership’s constant anti-corruption campaigns have been no more successful than those in the Soviet Union in the 1980s.

There is a causal link between all this and China’s frightful level of greenhouse gas emissions. Smith explains in his article the key role of so-called “hard to abate” industrial sectors – that is, processes that with current or anticipated technology can not easily be decarbonised. “Steel, aluminium, cement, aviation, shipping, chemicals, plastics, textiles and electronics stand out”, he writes.

Smith makes a strong case that these activities, which feed export markets and many of the waste-strewn domestic sectors, would have to be drastically curtailed under any effective climate policy. The “hard to abate” sectors account for 47% of China’s greenhouse gas emissions, compared to 32% from electricity generation, which dominates discussions on decarbonisation.

One analytical question that flows from Smith’s work is: where does useful production that improves people’s lives end, and wasteful production driven by twisted relationships of power and wealth, and mis-labelled “growth”, begin? No easy answer, either in China or globally.

4: China is the world’s number one investor in renewable energy, but will not come near to meeting climate targets unless it slashes fossil fuel use

On 12 December, Xi Jinping announced new 2030 climate targets at an on-line UN summit. The highlights were plans to raise wind and solar power generating capacity to 1200 gigawatts (GW), nearly three times the current 414 GW, and for fossil fuels’ share of the primary energy balance to go down to 75% from the current level of 88%. Environmental NGOs said that building wind and solar would not be enough to hit China’s own targets, leave alone targets that would forestall dangerous climate change. They estimate that 330 GW of China’s nearly 1100 GW of coal-fired capacity would have to be shut down too.

Smith, writing before this announcement, argued that, while China’s government is still building solar and wind, “it has effectively abandoned transitioning to renewables”. He points to still-rising emissions, ongoing investment in coal, expansion of coal-to-gas facilities and the gigantic infrastructure building programme announced in March. (Part of that is a carbon-heavy high-speed rail plan slammed by transport researchers as senseless.)

In his book (pages 76-79), Smith compares the bureaucratic regulation of Chinese electricity networks unfavourably with market-based systems. He points to the outrageous level of “curtailment” of wind and solar power (i.e. the deliberate reduction of available renewable power, keeping it behind coal-fired power in the queue for space on the grid).

Smith is overstating his case on renewables in two ways, I think. First: if the Chinese ruling elite put its mind to it, I have little doubt that it could expand wind and solar capacity rapidly. It has already accomplished some of the most astonishing infrastructure projects in history, including near-total electrification on one hand, and the boondoggles that Smith denounces on the other.

|

| Protesters against the new national security law gesture with five fingers, signifying the “Five demands – not one less” on 1 July 2020 |

Second: to build renewables infrastructure, state direction as opposed to market mechanisms might be an advantage. Throughout the history of capitalism it has almost always been state-directed investment that built railroads or electrified the countryside. Moreover, western electricity markets don’t work as well for renewables expansion as Smith implies. Once renewables capacity is built, the running costs are close to zero, prices fall on windy and sunny days, and that plays havoc with electricity companies’ revenues, which the markets prioritise.

For these reasons, I think massive expansion of wind and solar is possible in China. From the point of view of tackling dangerous climate change, though, this will be completely useless if such capacity is used not to replace coal but to give a new lease of life to blind, reckless and ecologically damaging expansion. Smith is right about that.

In a nightmare scenario, renewables capacity could be added to the world’s biggest coal-fired power system, to churn out more stuff of dubious use value, and at great human and natural cost. Smith writes:

Even if Xi were able to entirely replace fossil fuels with solar and wind, if he were to simply waste renewable energy producing more disposable products, needless consumerism, pointless overproduction and overconstruction, ‘blingfrastructure’ to glorify the Chinese Communist Party, ghost cities, damned-up rivers and paved-over forests, then the result would be the same: runaway global warming to climate collapse. There is just no way that Xi can ‘peak China’s emissions before 2030 and achieve carbon neutrality before 2060’ while also maximising growth.

There is some hyperbole in there, I think, but the last sentence is 100% right. That’s the nub of the issue. Renewables construction doesn’t take away the unsustainable character of capitalist expansion, in China or anywhere else.

5: It is the people of China, not its government, in whom we should put our hopes for change

In the last chapter of his book, Richard Smith surveys the democracy movement in Hong Kong. In contrast to those on the “left” who see the protests only through a geopolitical frame (of which more in a linked post), he welcomes the movement unequivocally, and hopes it will spread across China.

Xi’s “thuggish crackdown” on the protests have had the opposite of their intended effect, Smith argues (page 188); they have “deepened, broadened and empowered democratic forces”. It’s the worst set of outcomes for the CCP. While many in China “yearn for a transition to a capitalist democracy”, he writes (page 193):

[C]apitalism, democratic capitalism, or even ‘green capitalism’ is no solution for China’s environmental crisis, because around the world democratic capitalism and green capitalism are racing China off the cliff to extinction. […]

If humanity is to save itself, we have no choice but to cashier both Western capitalism and China’s communist capitalism and replace them both with some form of mostly publicly owned, and democratically planned and managed ecosocialist economy.

Smith doesn’t pretend to know how such changes will be achieved, or even which way things will turn out in China. But his starting point is the right one: what matters most is what people do, not what the state does.

In my view, one of the most important consequences of the Chinese boom is that, in the space of a few decades, it has brought into being a body of urban working-class people that numerically dwarfs the working class in Europe of the late 19th and early 20th centuries.

Social and labour movements are emerging in that vast class of people in ways about which we in Europe know little. Why should we expect those movements will be any less powerful, and any less decisive in shaping history, than the European workers’ movement of the 20th century to whose history we look?

Hopefully, Richard Smith’s book, and his article, will lead to wider discussion of the complex relationship between China and world capitalism, the causal connection between that and the climate and ecological crisis … and what we can all do about it. GL, 15 January 2021.

■ A linked post. China and the “left”: what planet are you people on?

Download both posts as a PDF here

■ China’s Engine of Environmental Collapse by Richard Smith: publisher’s information and a webinar.

■ The Chuang blog (in English) analysing Chinese capitalism and workers’ movements

■ Howey Ou, organiser of student climate strikes in China, on twitter.

On People & Nature:

■ China’s coal-fuelled boom: the man who cried stop

■ China: collective resistance against i-Slavery

⏭ Keep up with People And Nature. Follow People & Nature on twitter … instagram … telegram … or whatsapp. Or email peoplenature[at]yahoo.com, and you will be sent updates.

Great article but nothing can nor will happen until the Chinese City-States are directly affected by climate change. Then the people will demand action. Besides, Xi views himself as the new Mao and unless the supposed malcontents in the CCP decide to take action againsts him, he will play the long game. The English play cricket, the Chinese play cricket over decades.

ReplyDelete