|

|

That was significant as sports, mostly athletics but also the emerging field games such as rugby, soccer and hockey, were regarded as the pursuits of “gentlemen amateurs” who through various monetary and caste means sought to exclude working class and most rural folk from participation. Curiously, cricket which would be regarded as the epitome of English classism, was a much more open sport which was quite popular in places like Kilkenny and north county Dublin which are now GAA strongholds but where cricket still survives.

|

| Antique hurley owned by Michael Cusack. Photo Credit: HockeyGods |

That only became an issue as urban and rural working people began to have a bit more leisure time in the late 19th century. While in countries with large urban populations and socialist movements, the issue was a pretty straight forward one of allowing mass participation, in Ireland there was the added fact that native sports in common with our language, music, religious practices and others had been deliberately suppressed or undermined as part of weakening the Irish peoples’ sense of itself as something other than an extension of Britain.

It was fashionable then, as it is now, for those seeking to replace Irish identity with some nebulous concept of Britishness, or EUism, or class to ridicule the pursuits of the peasantry. Hence the modern far-left fantasy of “football”, as in soccer, being a unifying factor between the cloth-capped and mufflered proletarians of Ireland and Britain. That concept is rather undermined by the reality of soccer rivalries replicating the atavistic sectarianism that is evident when Cliftonville play Linfield, or Celtic play Rangers or when the two association football teams of Ireland meet on the pitch.

Cusack despite his radical position on the land question in opposition to landlordism, his support for Irish independence and sovereignty, and his egalitarianism in sport, has sometimes been ridiculed as a caricature of “backward nationalism.” That was promoted in no small way by Joyce’s depiction of him as The Citizen in the Cyclops episode of Ulysses in which Cusack is portrayed as a drunken anti-Semitic bigot. That has been comprehensively rejected by several historians including Cusack’s biographer Liam Ó Caithnia and former Cork Lord Mayor Gerald Goldberg.

Ironically one of the most notorious Dublin anti Semites of that era was Oliver St. John Gogarty who played soccer ball for the Bow-iss, currently guardians of all that is PC and woke in Irish sport, and several of whose Antifa members have no time for “the gah.”

|

| Dublin and Tipperary (as worn by Michael Hogan) jerseys from Bloody Sunday, 1920. Photo Credit: CrokePark |

Cusack’s antipathy to organised rugby, which he had played himself, and soccer was based on their bigotry not on his. Soccer was very much a sport of the British soldiery which became popular in Dublin and other towns with garrisons, while rugby was classist in the extreme; to the extent that private schools of all religious persuasions basically banned working class schools from participating in competitions, a practise that only ceased in Dublin in the 1980s. But of course none of our bien pensants go on endlessly about that.

Cusack’s own political opinions, apart from his nationalism, might also be divined from the fact that in 1887 he welcomed the success of the GAA in encouraging mass participation in hurling, football and athletics under the association’s rules (camogie was only systemised in 1903) as evidence of the growth of a “democratic Christian socialism.”

Patrick William Nally was more directly involved in the revolutionary movement. He was one of the founders of the Land League in Mayo in 1879 and became Joint Secretary and in 1880 was co-opted onto the Supreme Council of the Irish Republican Brotherhood as the Connacht representative. Nally was arrested in 1883 and convicted of an alleged plot to murder a landlord’s agent in Crossmolina. The only evidence was provided by two Special Branch informants at a time when British intelligence had deeply infiltrated the IRB. He was sentenced to ten years and thus missed the IRB meetings that were a prelude to its backing the foundation of the GAA in 1884.

Nally was first held in Downpatrick Gaol but was taken to Millbank prison in London to appear before the Parnell Commission in late 1888. That was part of the British attempt through the Times newspaper to implicate Parnell in revolutionary crime, but Nally refused to provide information to a ‘Thompson’ who visited them on behalf of the Times solicitor Soames. The Thompson in question was most likely Superintendent James Thomson who had been involved in secret operations against the Fenians under Sir Robert Anderson but who had retired in 1887.

Millbank was a dreadful place, built on marshes close to the Thames and regularly visited by outbreaks of dysentery, scurvy and other diseases. It had not had any prisoners since 1886 until Nally and other Fenians were held there to try and break them before the Commission. It was closed for good in 1890.

|

| Monument to Patrick W Nally in Balla, Co Mayo. Photo Credit: NMI |

Nally’s refusal to become an informer meant that his severe treatment continued on his return to Downpatrick prison. He was transferred to Mountjoy Prison in Dublin when Downpatrick closed in April 1891. He was said to have contracted typhoid in Downpatrick or Millbank, and when transferred to Mountjoy he was made to clean the piggery. He died there on November 9, 1891.

The inquest in Dublin found that Nally had died due to “harsh and cruel treatment” due to his refusal to comply (Freeman’s Journal, November 17, 1891.) The family had been represented at the inquest by Parnellite MP John Redmond who elicited from the Deputy Governor of Mountjoy John Conden, on being asked about the conditions of political prisoners, the reply: “I would not consider Moonlighters political prisoners.” (Freeman’s Journal. November 12, 1891.)

Nally’s defiance and association with the fledgling GAA led to the founding of the P.W Nally club in Dublin among whose key members were James Boland, Chairman of the Dublin GAA and father of Harry who hurled for Faughs and Dublin and was killed during the Civil War. James Boland had known Nally through the Fenians in Manchester. Members of the Nally Club led the funeral procession from Clarendon Street to Glasnevin and Nally’s coffin was draped in the same flag that had covered Parnell’s a month previously.

|

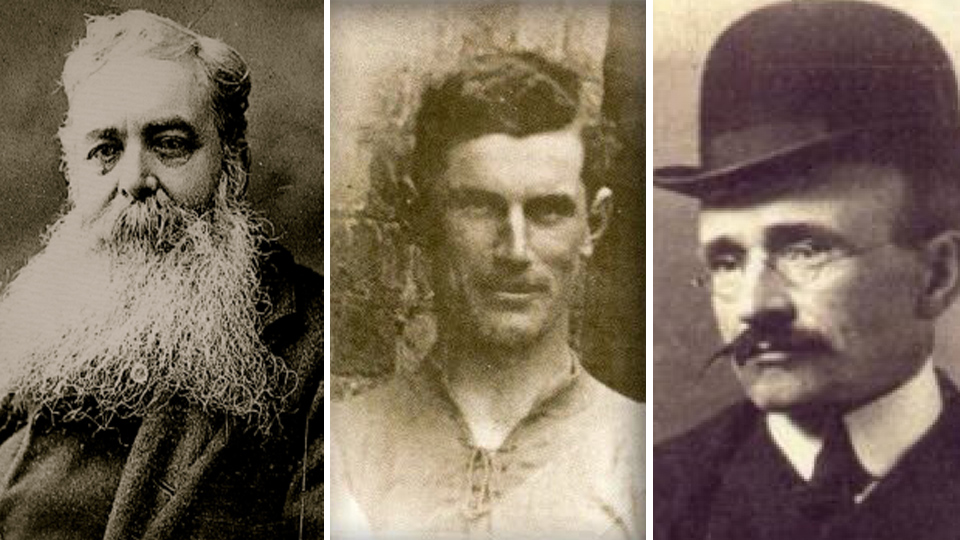

| Michael Cusack, múinteoir Gaeilge and founder of the Gaelic Athletic Association. Credit: NUI Galway |

Parnell of course, like Hogan, Nally and Cusack still holds a special place in the hearts of the GAA community as demonstrated by the number of clubs named in his honour, and of course Parnell Park in Dublin.

Matt Treacy has published a number of books including histories of the Republican Movement and of the Communist Party of Ireland.

He is currently working on a number of other books; His latest one is a novel entitled Houses of Pain. It is based on real events in the Dublin underworld. Houses of Pain is published by MTP and is currently available online as paperback and kindle while book shops remain closed.

He is currently working on a number of other books; His latest one is a novel entitled Houses of Pain. It is based on real events in the Dublin underworld. Houses of Pain is published by MTP and is currently available online as paperback and kindle while book shops remain closed.

Sean Mallory comments

ReplyDeleteReally enjoyed that Matt. I visited Cusack's home place in Carron many years ago but would pass it at least once a year while on holiday.....I think the GAA has lost its roots with its determination to revise its history to appeal to Unionism.

The question they should ask where Unionism is concerned is - 'do we want a sectarian, racist, bigoted pro British idealogy to have an influence in GAA?'...

Great reading Matt

ReplyDeleteSean Mallory I don't understand the appeal to Unionism statement to me the GAA has never been as strong much as it annoys most counties watching Dublin dominate has made the Gaa much stronger, since Peter Quinn had the vision to build a state of the art staduim and Sean Kelly the courage to remove the ban on foreign sports we have seen a massive increase in the support of our games,all clubs and county colours are worn with pride throughout this little troubled Island, from what I can see from the past 60 odd years is that yes we want everyone playing our games and please come and enjoy, the hand of friendship has been offered to Unionism for many years sometimes accepted sometimes not but as can seen from many GAA celebrations over the years we certainly have not lost or forgotten our roots

Sean Mallory comments

ReplyDeleteChrist, that response must have come from HQ!!!!

Why is there such a desire to have these people join us...they have nothing positive to bring to the table, not one thing...it isn’t an olive branch I would be offering but a blackthorn stick across their British backs. They will never be welcomed by me and as for that East Belfast Unionist GAA club...a club that has the cranes of H&W as it emblem, icons of Unionism / Orangism which are two institutions that are well known for having vigorously defended the GAA over the years....like fuck!!!! and doesnt fly the tricolour or play amhran na bhfiann in case it upsets their Unionist members....like seriously, WTF has that shipyard in common with the GAA? What's next? A tournament to commemorate those murdered at Narrow Water.....their language not mine!

We have lost our way Boyne Rover and also who we are...

"WTF has that shipyard in common with the GAA? "

DeleteIsn't there a GAA tournament named after Joe Cahill who worked in the Harland and Wolff shipyard for years? Oh wait, that doesn't fit the narrative...

"Why is there such a desire to have these people join us...they have nothing positive to bring to the table, not one thing...it isn’t an olive branch I would be offering but a blackthorn stick across their British backs."

"These people"

Not hard to see the sectarnism oozing from the pseudonym here, but why don't you just come on out and say it? It's not like we know your real name anyway?

"There is a distinct difference between offering the olive branch and being submissive!"

DeleteWho wants you to be submissive? My son plays Australian Rules and it's not hard to see the connection and the appeal. The East Belfast GAA is an attempt to give an olive branch to Unionism to connect with the sport but your threat of violence with the Blackthorn stick is exactly the reason why you can count the number of Prods involved in the game on a one handed leper. We still remember the naked sectaranian abuse given to the Fermangh (i think) Prod who wanted to play but was forced out.

But I don't blame you, you are a product of a fucked society but it's interesting to see Protestants becoming more and more interested in the Irish language and culture despite your resistence.

Is the GAA not supposed to be a non-sectarian organisation?

ReplyDeleteMy problem with gaelic football is that it is shite. Give me good British association football any day. 70 yards out and no passes available? Just fucking launch it over the bar! Zzzzzzz, boring as fuck. The most exciting part is watching them big country micks beat the bag out of each other. Can't beat a good GAA brawl. And clubs named after sectarian murderers and INLA kneecappers screams 'unionists not wanted'. Fair enough, I'll stick to real footy.

ReplyDeleteit is anything but shite - although many GAA fans think that of soccer. Bit of snobbishness either way, I think, While not a GAA fan, I have played the game and it is very skillful. Nor does the naming of clubs after dead republican activists mean that the GAA in general will not welcome unionists. It is a local club matter. If some Northern soccer team names itself after a dead loyalist or a British state combatant, I would not regard that as Northern soccer telling nationalists to get lost but a decision at a local level.

DeleteThe I am Offended Culture seeks to suffocate everything it does not approve. You wanna play for the UDR Rovers, I am not going to switch off or disengage.

Sean Mallory

ReplyDeleteWe as in the great GAA community

I take it by your comments that your not one for social interaction or being neighbourly but sure it takes all sorts

Sean Mallory comments

DeleteI don’t understand where the accusation of sectarianism is coming from? I never mentioned religion once.

My argument is straight forward – I do not see the addition of the ideology of Unionism to GAA sports as being something positive, in fact I would view it as quite a negative move. The GAA has a mixture of political thought and ideologies among its members but they all share the one common belief of its roots and its history.

Currently though, there are those among the membership who feel it is necessary to impose their politics through the implication of bringing the sport in to the 21st century to move away from that history and those roots and embark on a revisionist interpretation and embrace a cultural ideology that is not only alien to its ethos but from historical experience quite hostile to it. Even more recently that ideology has expressed that hostility and has shown no signs of changing. I oppose that and I do so unequivocally.

East Belfast GAA will never receive my support for they have abandoned the history and roots of the GAA in order to appease those who stood in their way for years....at times quite violently.

As two of my own sons play football and hurling, for two different clubs, I know of a lad who plays goals for a West Belfast club, a great wee keeper too, and he hails from the Shankill....that club made absolutely no changes to any of its practices but still welcomed him and his teams mates count him as one of their own. His father attends all the games and that’s how I discovered where he was from after commenting at a save he pulled off. I asked his father how he came to be interested in GAA and he said he always was himself and actually loved watching it but only in the house and always wanted to attend a match.

As luck would have it, he ended up working alongside the coach who remarked on his knowledge of the championship and after a while the coach asked him if he wanted to go to a game that he would take him and he did. He later mentioned that he wondered if he could get his lad involved and the coach asked him to bring his lad along to training and he did. He has been there ever since and is more than welcome.

There is a distinct difference between offering the olive branch and being submissive!

'It is anything but shite' in your opinion. I have tried to watch it and Aussie rules many times and can't be doing with it. Slapping the ball into the net? Get your head on it son! I treat it like bowls, horse racing and field hockey...shite.

ReplyDeleteThe Irish League would never allow a Vol. Top Gun McKeag FC and rightly so because that ballix has no place in sport.

these things are always opinion - your own as much as mine. Aussie rules is even more vigorous than Gaelic football but each to their own. Bowls and horse racing I don't watch. Hockey - can be ok. Thought the Irish team did great in the World Cup.

DeleteThe Irish League has a senior former RUC member as chairman of the Irish Football Association. Have I a problem with that? No. I hope he does a good job.

I don't care if the top man is ex-RUC or ex-IRA, but calling a club after an INLA kneecapper or UFF gunman for example, should not have any part in sport. You are politicising your sport and cheapening it. Good luck to East Belfast and to the Irish Guards over in London for sending the extremists nuts but I'll not be watching.

ReplyDeletewould that objection extend to calling it after cops or British troops? No idea what the Irish Guards reference is to

DeleteYes it would. Sport should be free from politicisation, a neutral space. I'm even uneasy about poppy day displays.

ReplyDeleteThe Irish Guards HQ in London has a gaelic football team and they applied to join the London league sending the republicans into meltdown. Which was nice.

I think there is merit in your argument.

DeleteIrish Guards team - shows the extent of my interest in the game

Sean Mallory

ReplyDeleteIve read both your comments and am at a loss to get your point like what have the GAA conceded or given up to placate anyone ???