|

Human sexuality and technology.

A trope that has become all too commonplace in the 21st century.

From phone sex, through to Tinder and robotic sex dolls, we now seem to crave the act without the human interaction. Whether that is the power of modern technology, or the human species is at a dead end (genetically speaking) is up for debate.

What's often left out of the debate is that we were warned about this by one of the greatest writers to have walked this earth.

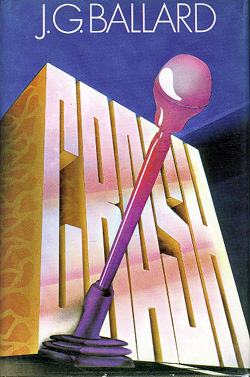

First published in 1973 (after being rejected by various publishers, including one where a reader wrote "This author is beyond psychiatric help. Do Not Publish"), Crash remains a work that is utterly engulfing, utterly unforgettable and utterly magnificent.

The plot itself is fairly simple: James Ballard has a car accident in which he kills a man and hospitalises himself. However, the crash itself is an epiphany for him:

After being bombarded endlessly by road-safety propaganda it was almost a relief to find myself in an actual accident. After the commonplaces of everyday life, with their muffled dramas, all my organic expertise for dealing with physical injury had long been blunted or forgotten. The crash was the only real experience I had been through for years.

Quickly, he realises that his sexual inclinations have moved towards car crashes and the meshing of the most base human act with the most damaged piece of machinery that most of us rely on from day to day is one that is utterly uplifting and life affirming for him:

Once together in my car, with the crowded traffic lanes through which we had moved forming an unseen and unseeing audience, we were able to arouse each other. Each time she revealed a growing tenderness towards myself and my body, even trying to allay my concern for her. In each sexual act together we recapitulated her husband's death, re-seeding the image of his body in her vagina in terms of the hundred perspectives of our mouths and thighs, nipples and tongues within the metal and vinyl compartment of the car.

Meeting Vaughan, whose ultimate goal is to die in a car crash with Elizabeth Taylor, sees events move far quicker and introduces James to other people who live their lives through car accidents and sexual acts.

Originally billed as "a brutal, erotic novel," Ballard takes pornography and substitutes the bodies with machinery. What we are left with is a novel that fetishises the unfetishable, and the distinction between the clean, clinical world of the machinery (which works on the basis of A and B working to produce C) and the messy, individualistic needs of humans (who work on irrationality).

This (pardon the pun) collision of two different worlds throws up interesting ideas about us humans: are we truly controlled by our desires, or are we being controlled by technology? If it is the latter, then is fucking the technology an act of rebellion, or is it a new human need? In Crash, it seems to be both.

Vaughan's obsession with Elizabeth Taylor and his desire to die with her can be seen as an early allegory for our obsession with the seeming purity and unabashed freedom that celebrities offer. By inducting Taylor into the car crash sect, there is no difference between the average person and a celebrity. Both are piled together by humanity's re-rendering of technology for their own end.

Ballard once claimed that his objective with Crash was "... to rub the human face in its own vomit and force it to look in the mirror." He certainly achieved this, but there's so much more to the novel than a forewarning.

It looks at how human sexuality is purely functional and fluid (James ends up having sex with Vaughan and notes afterwards that in "... our wounds we celebrated the re-birth of the traffic-slain dead, the deaths and injuries of those we had seen dying by the roadside and the imaginary wounds and postures of the millions yet to die"), our willingness to hand our freedom over for convenience (the car crash sect are almost zombie like in their devotion to crashes) and mob mentality (Vaughan's desire to crash into Elizabeth Taylor is considered perfectly normal by the sect).

Considered unfilmable for many years, 1996 saw an adaptation hit the screens by way of the legendary David Cronenberg (who had adapted another unfilmable novel, William Burroughs' Naked Lunch, in 1990). Still controversial, Portadown born Alexander Walker (film critic for the Evening Standard, and personal friend of Stanley Kubrick) described the film as containing:

some of the most perverse acts and theories of sexual deviance I have seen propagated in mainstream cinema - Crash, without exaggeration, will tax public tolerance and film censorship to the limits and maybe beyond.

Walker had form for such behaviour: he heckled a Cannes screening of Ken Loach's Hidden Agenda as he believed the film was IRA propaganda, described Fight Club as fascistic as well as anti God and, according to The Telegraph, "When Jane Fonda appeared at the National Film Theatre in 1974 with a film on Vietnam, he asked if she was going to attack the Soviet regime's 'pogroms' when she went to Moscow; he then incurred the wrath of some present by being unsatisfied by her reply that she was not going to point the finger at anyone 'until the blood of Indo-China is off the hands of the American government.' "

Although Walker never called for the film to be banned, his review started off a chain of events that would lead to the Daily Mail to openly call for the banning of the film. All for a film that had its origins in a book from 1973 by a critically acclaimed author? That's the power of literature.

Certainly not an easy read but, when approached with an open mind, will leave you thinking of nothing else but it for a few weeks.

JG Ballard Crash 1973 HarperCollins Publishers ISBN-13: 978-0099334910

Christopher Owens reviews for Metal Ireland and finds time to study the history and inherent contradictions of Ireland.

Follow Christopher Owens on Twitter @MrOwens212

No comments