People in Moscow may soon get a chance to vote to return a statue of Feliks Dzerzhinsky, founder of the Soviet secret police, to the plinth in Lubyanka square from which it was toppled in 1991.

The ballot – which will go ahead if an initiative group, sanctioned by the city council, collects 140,000-odd signatures supporting it – comes at a time when Soviet symbols, especially second world war symbols, are being called into service to justify Russian aggression against Ukraine. History is being mobilised to buttress the image of a strong Russian state, which president Vladimir Putin’s propagandists claim is a crucial bastion against western, above all American, geopolitical domination.

Dzerzhinsky, a Polish socialist freed from Moscow’s Butyrka prison during the 1917 revolution before taking charge of the Soviet state’s rudimentary security service, would be horrified; he despised all nationalisms great and small. But this is not about him. It’s about a statue that stood outside the security service’s headquarters where oppositionists and dissidents were detained from Dzerzhinsky’s time. After his death in 1926, and especially in the mid and late 1930s, the number of detainees swelled tens and hundreds of times over; they were interrogated, tortured and then shot or deported to the Gulag.

In August 1991, a crowd of demonstrators tried to topple the giant monument. They were celebrating the defeat of the state committee of emergency, a bunch of security services and army chiefs who had detained the last Soviet leader, Mikhail Gorbachev, and planned to clamp down on democractic practices – freedom of speech and assembly, multiparty elections, etc – that he had approved. Their coup lasted only three days; Gorbachev returned, and five months later dissolved the Soviet Union.

Then, the city authorities brought a crane to lower the Dzerzhinsky statue safely. Now, they have set in motion the procedure to hold a referendum on its return, after a campaign by the city’s branch of the Communist Party of the Russian Federation (CPRF), the main stalinist successor to the Communist Party of the Soviet Union the end of whose rule was marked by the statue’s removal.

CPRF members of the city council proposed referenda on health and education reforms along with the one on Dzerzhinsky. At first the council majority rejected all three, but on 25 June had a change of heart about the statue. Why? The political rumour-mill had no doubt: “our officals have become used to taking decisions only on a distinct signal from above”, Dmitry Kamyshev, a journalist on the business newspaper Vedomosti, observed. These days, those signals favour a positive view of the Soviet Union under Stalin as a bearer of great Russian statehood (or, more accurately, state-ism (gosudarstvennost’)).

If the poll goes ahead, there’s a fair chance it will approve the statue’s return. In 2013 the authoritative Public Opinion Research Centre (VTsIOM) found almost a two-to-one majority in favour. (To be exact, 25% supported the statue’s return and 20% supported it more than opposed it (making 45%); 14% opposed it and 11% opposed it more than supported it (making 25%); 30% said the question was “difficult to answer”.)

I don’t claim to know what goes on in people’s heads, but my guess is that reasons for favouring the statue’s return include a hankering after a strong Russian state; approval for Putin’s state-centred nationalism; and nostalgia for the Soviet Union of living memory, i.e. of the comparatively stable 1970s. None of these motivations will have weakened since 2013, after a year of war in Ukraine and sanctions by the western powers.

The 1917 revolution is out

The Kremlin has said nothing about the Dzerzhinsky statue. (Political commentators suggested it would point to the referendum – as it did to the candidacy of oppositionist Alexei Navalny in last year’s mayoral election – as evidence that tolerance and democracy thrive.) But president Putin has made very clear that he regards the second revolution of 1917, which overthrew the provisional government and brought the Bolsheviks to power, as anathema to the traditions of statehood with which the population should be instilled.

The movement for “bread, peace and land” that swept out the provisional government had betrayed “national interests”, Putin said last summer at the Seliger forum, organised by pro-Kremlin youth groups. He compared these “traitors” in 1917 to liberals and socialists of today who have opposed Russian support for Ukrainian separatist forces.

“The Bolsheviks openly wished their motherland to be defeated in the first world war”, Putin said (see RT report here).

This picture of “heroic soldiers” shedding their blood, only to be let down by saboteurs at home, bears little relation to what actually happened. Upheavals in the army and navy – together with actions by urban workers and peasants – were a crucial part of the process by which the provisional government was driven from power. The soldiers’ movement had begun during the February revolution with a refusal to fire on demonstrators; barracks hierarchies had been dismantled by the soviets’ Order no. 1, which required orders to be countersigned by soviet representatives and abolished key officers’ privileges; the revolt had spread to the front with the formation of committees that refused to accept orders unless countersigned by pro-revolutionary soviets; among the outcomes in the trenches were the establishment of soldiers’ action committees, widespread refusals to obey orders, fraternisation with soldiers in the trenches opposite, and mass desertions.

Putin reiterated his view on 1917 at a meeting with history teachers in the Kremlin in February this year. Russia was “torn apart from within”, he said; “Russia lost enormous territories, did not achieve anything aside from colonial losses.”

And these are not just personal opinions. The state needs to take a political view on history, he said at the Seliger event. “I consider that a unified conception of history teaching and textbook are needed. […] What’s needed is a canonical version, with the aid of which talented teachers can put over their point of view to students.”

Clearly this “canonical version” includes a positive view of the Russian Orthodox church, which under Putin has been restored to its most powerful position in public life since 1917. Some voices in the political establishment also urge a place for the Romanov family, who ruled Russia for hundreds of years before being ousted by the February 1917 revolution.

On 23 June, while the Moscow city councillors were discussing the Dzerzhinsky statue, the pro-government newspaper Izvestiia reported that Vladimir Petrov, a deputy in the Leningrad regional legislature, had written to Romanov family representatives inviting them to return to Russia. “At present a difficult process is underway, of the restoration of Russia’s might and the return of her global influence”, Petrov’s letter to princess Maria Vladimirovna and prince Dmitry Romanovich said. “The tsar’s heirs could play an important symbolic role in Russian society.” The Romanovs responded positively.

Stalin, as war hero, is in

So the “canonical” version involves burying the 1917 revolution, and painting favourably the bloodthirsty crimes of the KGB. But above all it is about mythologising the Soviet victory over Nazi Germany, and Stalin’s role in it, which has moved to the centre of Putin’s system of symbols. The shift has been driven by war: it came last year after Moscow annexed Crimea, and sanctioned the supply of large quantities of heavy weapons to the eastern Ukrainian separatists and armed support for them by ultranationalist volunteers, mercenaries, and an unknown numbers of Russian troops.

At the meeting with history teachers, Putin not only contrasted victory in the second world war to the “defeat from within” in the first, but also mounted a spirited defence of the Soviet-German pact (signed by foreign ministers Vyacheslav Molotov and Joachim von Ribbentrop) of August 1939, which, he said, had avoided war and given the

Soviet forces time to prepare for conflict should it be forced on them. He passed over in silence the controversial secret clauses of the pact that divided eastern Europe into Nazi and Soviet spheres of influence, and in the light of which Soviet forces carved up Poland with the German army and invaded Finland, and the Soviet Union annexed the Baltic states.

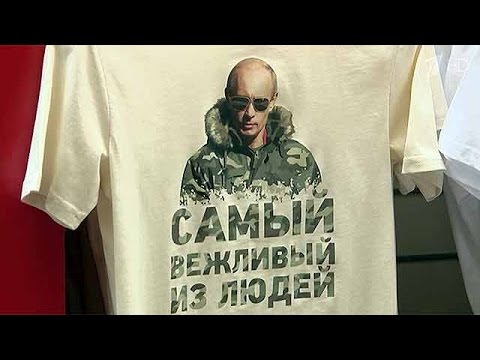

The symbolism is not only in classrooms, but also in the streets and workplaces and on TV screens. I have been visiting Russia for a long time, and last month really noticed the difference. Putin T-shirts are everywhere; some of them quoting his aphorism, “polite people”, coined to describe Russian special forces agents who appeared in Crimea in March last year. The folklorisation of the second world war has intensified.

“Thanks for the victory, grandad”, the car stickers say, many of them with an image of Stalin. The volume of crude, strident propaganda in so-called current affairs and history shows on TV has expanded.

It has been argued that the urban intelligentsia (who almost always shape the view of western visitors) are at odds with the rest of Russia, where chauvinism is fiercer. I am not so sure: in my experience, the euphoric response to the annexation of Crimea swept up plenty of the intelligentsia too. A friend in a high-flying research job reflected on the melancholy he felt when he visited Berlin. Why? “Because we won, and they live like that” (that is, better than Russians), he said. A university lecturer from Central Asia, whose family is Russian, enthused to me about her holiday in Crimea this summer; it was a patriotic duty to go to the annexed peninsula.

Another acquaintance of more liberal views, a man in a senior academic post, said gloomily over coffee:

Like many in the business and academic elites, my acquaintance is heartily sick of Russia’s role in the Ukraine conflict and the increasing coldness in Putin’s relationship with the western powers. But he doesn’t expect it to change for a long time.

The Ukrainian response

The Ukrainian government has begun to distort, rewrite and mobilise history for propaganda purposes just as enthusiastically as the Kremlin. On 15 May president Petro Poroshenko signed four laws that politicised history – despite acknowledging parts of them were vague and otherwise flawed, despite the fact that they were rushed through parliament with the scantest of discussion (they were tabled on 3 April and voted through six days later), and despite widespread opposition by historians and human rights organisations.

The law “On the Legal Status and Honouring of Fighters for Ukraine’s Independence in the Twentieth Century” recognises the Ukrainian Insurgent Army (UPA) as second world war veterans, and outlaws any “public denial of the legitimacy of the struggle for Ukraine’s independence”. Lawyers and human rights activists say that it tries to impose a particular view of history, and that its wording could endanger public discussion of controversial episodes in the UPA’s history, such as collaboration by some leaders with Nazi Germany and participation by UPA members in racist massacres of Poles and Jews e.g. in Volynia in 1943.

A second law, “On Condemning the Communist and Nazi Totalitarian Regimes and Prohibiting Propaganda of Their Symbols”, bans the flags and symbols of the Soviet Union and Nazi Germany – but not those of Ukrainian fascist organisations – and outlaws “public denial of the criminal nature of the communist totalitarian regime of 1917-1991 in Ukraine”. It exempts history teaching from the ban on symbols, but with the condition “that this does not lead to denial of the criminal nature of the communist totalitarian regime”, a phrase that can only censor and obstruct historical education. The law requires the renaming of hundreds of thousands of streets, buildings, towns and cities named after Soviet leaders and officials.

A third law provides for the 9 May “Victory day” celebration to be replaced with a “Day of Memory and Reconciliation”, but also prohibits “falsification of the history of the second world war”. Crucially, it makes no mention of what constitutes “falsification”, and who is to decide on that. The fourth law passed puts state archives of the Soviet period under the jurisdiction of the Institute for National Remembrance, a politicised body dominated by ultranationalists.

Halya Coynash of the Kharkiv Human Rights Protection Group has shown in a series of eloquent articles (for example, here) that the vague wording of the laws aims to impose a particular view of history on Ukrainians, and is thus fundamentally anti-democratic.

“What constitutes ‘disrespect’ or ‘denigration’ [of “fighters for Ukrainian independence”] and who is to decide this?” she asks. “Are we seriously to believe that all research, for example, into the 1943 Volynia massacre will remain unimpeded by such prohibitions? What if we strongly deny that the members of the UPA, implicated in such ethnic cleansing, were serving the cause of Ukraine’s independence?”

Coynash challenges Volodymyr Viatrovych of the Institute for National Remembrance, who worked on drafting the laws, has championed the image of the UPA leaders Stepan Bandera and Roman Shukhevych, and in his historical writing has presented a sugar-coated version of the Volynia massacre that has been widely criticised.

Viatrovich has said that the laws are aimed at undermining “bearers of Soviet values” who, he asserts, are the support base for separatism.

But, Coynash points out, the views of many Ukrainians in the southeast of the country – who have a positive or mixed view of the Soviet past, while also identifying themselves as Ukrainian and opposing separatism – have been “entirely ignored by parliamentarians who believe that they can impose ‘correct’ attitudes regarding Ukraine’s history via legislation.”

“By no means all Ukrainians view all aspects of the regime from 1917 to 1991 as criminal”, Coynash writes. But “the message given [by the laws] to a significant percentage of Ukrainians, especially in Donbas, will be that their views are not respected and must be changed. At a time when Russia is waging undeclared war with Ukraine and seeking any opportunity to divide Ukrainians, the ramifications of sending such a message for the very security of the country are enormous.”

A century after the first world war, a military conflict in Europe, fuelled by a would-be great power, Russia, has claimed the lives of thousands of Ukrainians. It has wrecked the economy, turned Ukrainian communities against each other and weakened social and labour movements. In Russia itself, state-fostered militarism and nationalism are being used to shield a government shaken by economic crisis, which in 2011-12 was becoming alarmed at a growing protest movement in its own big cities. History has been conscripted to fight on both sides. Along with the people on both sides, it needs to be freed from this call-up. GL, 9 July 2015.

Also on People & Nature:

Workers’ solidarity in wartime: Bosnia 1993, Ukraine 2015

Ukraine: war as a means of social control

|

This is not about him. Feliks Dzerzhinsky (centre) with a group of officers from the Cheka security service during the Russian civil war

|

In August 1991, a crowd of demonstrators tried to topple the giant monument. They were celebrating the defeat of the state committee of emergency, a bunch of security services and army chiefs who had detained the last Soviet leader, Mikhail Gorbachev, and planned to clamp down on democractic practices – freedom of speech and assembly, multiparty elections, etc – that he had approved. Their coup lasted only three days; Gorbachev returned, and five months later dissolved the Soviet Union.

Then, the city authorities brought a crane to lower the Dzerzhinsky statue safely. Now, they have set in motion the procedure to hold a referendum on its return, after a campaign by the city’s branch of the Communist Party of the Russian Federation (CPRF), the main stalinist successor to the Communist Party of the Soviet Union the end of whose rule was marked by the statue’s removal.

|

August 1991: Dzerzhinsky’s statue being taken down. The Lubyanka police headquarters ins in the background. From RIA Novosti

|

If the poll goes ahead, there’s a fair chance it will approve the statue’s return. In 2013 the authoritative Public Opinion Research Centre (VTsIOM) found almost a two-to-one majority in favour. (To be exact, 25% supported the statue’s return and 20% supported it more than opposed it (making 45%); 14% opposed it and 11% opposed it more than supported it (making 25%); 30% said the question was “difficult to answer”.)

I don’t claim to know what goes on in people’s heads, but my guess is that reasons for favouring the statue’s return include a hankering after a strong Russian state; approval for Putin’s state-centred nationalism; and nostalgia for the Soviet Union of living memory, i.e. of the comparatively stable 1970s. None of these motivations will have weakened since 2013, after a year of war in Ukraine and sanctions by the western powers.

The 1917 revolution is out

The Kremlin has said nothing about the Dzerzhinsky statue. (Political commentators suggested it would point to the referendum – as it did to the candidacy of oppositionist Alexei Navalny in last year’s mayoral election – as evidence that tolerance and democracy thrive.) But president Putin has made very clear that he regards the second revolution of 1917, which overthrew the provisional government and brought the Bolsheviks to power, as anathema to the traditions of statehood with which the population should be instilled.

The movement for “bread, peace and land” that swept out the provisional government had betrayed “national interests”, Putin said last summer at the Seliger forum, organised by pro-Kremlin youth groups. He compared these “traitors” in 1917 to liberals and socialists of today who have opposed Russian support for Ukrainian separatist forces.

“The Bolsheviks openly wished their motherland to be defeated in the first world war”, Putin said (see RT report here).

When heroic soldiers and officers were shedding blood at the front, some people were rocking Russian from the inside, and this rocking caused the country to engineer its own defeat. It was a nonsense, a delirium.

This picture of “heroic soldiers” shedding their blood, only to be let down by saboteurs at home, bears little relation to what actually happened. Upheavals in the army and navy – together with actions by urban workers and peasants – were a crucial part of the process by which the provisional government was driven from power. The soldiers’ movement had begun during the February revolution with a refusal to fire on demonstrators; barracks hierarchies had been dismantled by the soviets’ Order no. 1, which required orders to be countersigned by soviet representatives and abolished key officers’ privileges; the revolt had spread to the front with the formation of committees that refused to accept orders unless countersigned by pro-revolutionary soviets; among the outcomes in the trenches were the establishment of soldiers’ action committees, widespread refusals to obey orders, fraternisation with soldiers in the trenches opposite, and mass desertions.

Putin reiterated his view on 1917 at a meeting with history teachers in the Kremlin in February this year. Russia was “torn apart from within”, he said; “Russia lost enormous territories, did not achieve anything aside from colonial losses.”

And these are not just personal opinions. The state needs to take a political view on history, he said at the Seliger event. “I consider that a unified conception of history teaching and textbook are needed. […] What’s needed is a canonical version, with the aid of which talented teachers can put over their point of view to students.”

Clearly this “canonical version” includes a positive view of the Russian Orthodox church, which under Putin has been restored to its most powerful position in public life since 1917. Some voices in the political establishment also urge a place for the Romanov family, who ruled Russia for hundreds of years before being ousted by the February 1917 revolution.

On 23 June, while the Moscow city councillors were discussing the Dzerzhinsky statue, the pro-government newspaper Izvestiia reported that Vladimir Petrov, a deputy in the Leningrad regional legislature, had written to Romanov family representatives inviting them to return to Russia. “At present a difficult process is underway, of the restoration of Russia’s might and the return of her global influence”, Petrov’s letter to princess Maria Vladimirovna and prince Dmitry Romanovich said. “The tsar’s heirs could play an important symbolic role in Russian society.” The Romanovs responded positively.

Stalin, as war hero, is in

So the “canonical” version involves burying the 1917 revolution, and painting favourably the bloodthirsty crimes of the KGB. But above all it is about mythologising the Soviet victory over Nazi Germany, and Stalin’s role in it, which has moved to the centre of Putin’s system of symbols. The shift has been driven by war: it came last year after Moscow annexed Crimea, and sanctioned the supply of large quantities of heavy weapons to the eastern Ukrainian separatists and armed support for them by ultranationalist volunteers, mercenaries, and an unknown numbers of Russian troops.

At the meeting with history teachers, Putin not only contrasted victory in the second world war to the “defeat from within” in the first, but also mounted a spirited defence of the Soviet-German pact (signed by foreign ministers Vyacheslav Molotov and Joachim von Ribbentrop) of August 1939, which, he said, had avoided war and given the

|

“Thanks for the victory, grandad”. Comes as a car sticker or a big banner like this for your picnic

|

The symbolism is not only in classrooms, but also in the streets and workplaces and on TV screens. I have been visiting Russia for a long time, and last month really noticed the difference. Putin T-shirts are everywhere; some of them quoting his aphorism, “polite people”, coined to describe Russian special forces agents who appeared in Crimea in March last year. The folklorisation of the second world war has intensified.

“Thanks for the victory, grandad”, the car stickers say, many of them with an image of Stalin. The volume of crude, strident propaganda in so-called current affairs and history shows on TV has expanded.

It has been argued that the urban intelligentsia (who almost always shape the view of western visitors) are at odds with the rest of Russia, where chauvinism is fiercer. I am not so sure: in my experience, the euphoric response to the annexation of Crimea swept up plenty of the intelligentsia too. A friend in a high-flying research job reflected on the melancholy he felt when he visited Berlin. Why? “Because we won, and they live like that” (that is, better than Russians), he said. A university lecturer from Central Asia, whose family is Russian, enthused to me about her holiday in Crimea this summer; it was a patriotic duty to go to the annexed peninsula.

|

“The politest of people”. From modnayaobuv.ru

|

Another acquaintance of more liberal views, a man in a senior academic post, said gloomily over coffee:

On Victory Day [9 May, commemorating the Soviet defeat of Nazi Germany] this year, it seemed like every second car had a sticker saying ‘We went to Berlin in 1945; we can go again’. That’s not funny. The ‘party of war’ is in the ascendancy: [deputy prime minister] Sergei Ivanov, [emergencies minister] Sergei Shoigu, [federal security services head] Nikolai Patrushev and the rest. They profit from this tension with the west and the instability in eastern Ukraine. Putin couldn’t back off even if he wanted to; these guys wouldn’t let him.

Like many in the business and academic elites, my acquaintance is heartily sick of Russia’s role in the Ukraine conflict and the increasing coldness in Putin’s relationship with the western powers. But he doesn’t expect it to change for a long time.

The Ukrainian response

The Ukrainian government has begun to distort, rewrite and mobilise history for propaganda purposes just as enthusiastically as the Kremlin. On 15 May president Petro Poroshenko signed four laws that politicised history – despite acknowledging parts of them were vague and otherwise flawed, despite the fact that they were rushed through parliament with the scantest of discussion (they were tabled on 3 April and voted through six days later), and despite widespread opposition by historians and human rights organisations.

The law “On the Legal Status and Honouring of Fighters for Ukraine’s Independence in the Twentieth Century” recognises the Ukrainian Insurgent Army (UPA) as second world war veterans, and outlaws any “public denial of the legitimacy of the struggle for Ukraine’s independence”. Lawyers and human rights activists say that it tries to impose a particular view of history, and that its wording could endanger public discussion of controversial episodes in the UPA’s history, such as collaboration by some leaders with Nazi Germany and participation by UPA members in racist massacres of Poles and Jews e.g. in Volynia in 1943.

A second law, “On Condemning the Communist and Nazi Totalitarian Regimes and Prohibiting Propaganda of Their Symbols”, bans the flags and symbols of the Soviet Union and Nazi Germany – but not those of Ukrainian fascist organisations – and outlaws “public denial of the criminal nature of the communist totalitarian regime of 1917-1991 in Ukraine”. It exempts history teaching from the ban on symbols, but with the condition “that this does not lead to denial of the criminal nature of the communist totalitarian regime”, a phrase that can only censor and obstruct historical education. The law requires the renaming of hundreds of thousands of streets, buildings, towns and cities named after Soviet leaders and officials.

A third law provides for the 9 May “Victory day” celebration to be replaced with a “Day of Memory and Reconciliation”, but also prohibits “falsification of the history of the second world war”. Crucially, it makes no mention of what constitutes “falsification”, and who is to decide on that. The fourth law passed puts state archives of the Soviet period under the jurisdiction of the Institute for National Remembrance, a politicised body dominated by ultranationalists.

Halya Coynash of the Kharkiv Human Rights Protection Group has shown in a series of eloquent articles (for example, here) that the vague wording of the laws aims to impose a particular view of history on Ukrainians, and is thus fundamentally anti-democratic.

“What constitutes ‘disrespect’ or ‘denigration’ [of “fighters for Ukrainian independence”] and who is to decide this?” she asks. “Are we seriously to believe that all research, for example, into the 1943 Volynia massacre will remain unimpeded by such prohibitions? What if we strongly deny that the members of the UPA, implicated in such ethnic cleansing, were serving the cause of Ukraine’s independence?”

Coynash challenges Volodymyr Viatrovych of the Institute for National Remembrance, who worked on drafting the laws, has championed the image of the UPA leaders Stepan Bandera and Roman Shukhevych, and in his historical writing has presented a sugar-coated version of the Volynia massacre that has been widely criticised.

Viatrovich has said that the laws are aimed at undermining “bearers of Soviet values” who, he asserts, are the support base for separatism.

But, Coynash points out, the views of many Ukrainians in the southeast of the country – who have a positive or mixed view of the Soviet past, while also identifying themselves as Ukrainian and opposing separatism – have been “entirely ignored by parliamentarians who believe that they can impose ‘correct’ attitudes regarding Ukraine’s history via legislation.”

“By no means all Ukrainians view all aspects of the regime from 1917 to 1991 as criminal”, Coynash writes. But “the message given [by the laws] to a significant percentage of Ukrainians, especially in Donbas, will be that their views are not respected and must be changed. At a time when Russia is waging undeclared war with Ukraine and seeking any opportunity to divide Ukrainians, the ramifications of sending such a message for the very security of the country are enormous.”

A century after the first world war, a military conflict in Europe, fuelled by a would-be great power, Russia, has claimed the lives of thousands of Ukrainians. It has wrecked the economy, turned Ukrainian communities against each other and weakened social and labour movements. In Russia itself, state-fostered militarism and nationalism are being used to shield a government shaken by economic crisis, which in 2011-12 was becoming alarmed at a growing protest movement in its own big cities. History has been conscripted to fight on both sides. Along with the people on both sides, it needs to be freed from this call-up. GL, 9 July 2015.

Also on People & Nature:

Workers’ solidarity in wartime: Bosnia 1993, Ukraine 2015

Ukraine: war as a means of social control

No comments