I show that this consensus is mistaken: there is in fact direct opinion poll evidence suggesting that a majority for a united Ireland will emerge in the north. In this sense, Irish unity is in the forecast. But the forecast does not mean that a border poll will necessarily follow.

The Weather Deniers

The Good Friday Agreement and Northern Ireland Act require that the Secretary of State call a border poll once he believes that a majority of voters would back Irish unity. This “mandatory duty”—which I address more fully later—frames much of the debate about the possibility of a united Ireland. For years, the Northern Ireland Office has been retelling the same old story: the Secretary of State is under no legal obligation to hold a border poll because his view is that there is no hint anywhere of an emergent majority for unity.[1]

The British and Irish governments, sundry politicians, and many commentators and academics are at one in denying that a united Ireland is in the offing. Before becoming Prime Minister, Keir Starmer set out his position on the prospect of a border poll on Irish unity: “I don't think we're anywhere near that kind of question, it's absolutely hypothetical. It's not even on the horizon.” (Bain, 2023).[2] In September 2024, Prime Minister Starmer’s Secretary of State, Hilary Benn, echoed the standard NIO line and repeated his leader’s comments that a pro-unity majority is not in sight: “There is no evidence in Northern Ireland that that is the view of the people” (BBC, 2024).

The current Irish government takes the same position. On winning the 2024 election, coalition partners Micheál Martin and Simon Harris emphasized that unification is not their priority (Paun, Sargeant & Fright, 2024). Taoiseach Martin, in a recent and extended interview with Sam McBride of the Belfast Telegraph, delineated his position on north-south matters. In response to the campaign to hold a border poll by the end of the decade, Martin said his government is “not planning for a border poll in 2030.” McBride characterizes Martin as “someone now confident to make clear he doesn't think Irish unity is on the horizon and will only happen after patient unglamorous toil.” Columnist Suzanne Breen adds to McBride’s view in specifying the extended reach of Martin’s horizon:

The Weather Deniers

The Good Friday Agreement and Northern Ireland Act require that the Secretary of State call a border poll once he believes that a majority of voters would back Irish unity. This “mandatory duty”—which I address more fully later—frames much of the debate about the possibility of a united Ireland. For years, the Northern Ireland Office has been retelling the same old story: the Secretary of State is under no legal obligation to hold a border poll because his view is that there is no hint anywhere of an emergent majority for unity.[1]

The British and Irish governments, sundry politicians, and many commentators and academics are at one in denying that a united Ireland is in the offing. Before becoming Prime Minister, Keir Starmer set out his position on the prospect of a border poll on Irish unity: “I don't think we're anywhere near that kind of question, it's absolutely hypothetical. It's not even on the horizon.” (Bain, 2023).[2] In September 2024, Prime Minister Starmer’s Secretary of State, Hilary Benn, echoed the standard NIO line and repeated his leader’s comments that a pro-unity majority is not in sight: “There is no evidence in Northern Ireland that that is the view of the people” (BBC, 2024).

The current Irish government takes the same position. On winning the 2024 election, coalition partners Micheál Martin and Simon Harris emphasized that unification is not their priority (Paun, Sargeant & Fright, 2024). Taoiseach Martin, in a recent and extended interview with Sam McBride of the Belfast Telegraph, delineated his position on north-south matters. In response to the campaign to hold a border poll by the end of the decade, Martin said his government is “not planning for a border poll in 2030.” McBride characterizes Martin as “someone now confident to make clear he doesn't think Irish unity is on the horizon and will only happen after patient unglamorous toil.” Columnist Suzanne Breen adds to McBride’s view in specifying the extended reach of Martin’s horizon:

it's not just a border poll by 2030, as Sinn Féin is calling for, that Martin rejects. It appears that, as far as he sees it, one isn't even on the horizon in the next half century.

Dublin, then, is not planning for Irish unity because it believes that a united Ireland, if it arrives at all, is way off in the distant future. Martin also rejects the suggestion that his Shared Island initiative has anything to do with Irish unification. As he told McBride: “it's not part of a political project or anything like that and it's most certainly not a Trojan horse” (McBride, 2025a; Breen, 2025). Martin, it seems, actively shuns anything to do with a united Ireland.

A succession of DUP leaders also dismiss the prospect of unification. Both Arlene Foster and Jeffrey Donaldson insist that they would not see a border poll or a united Ireland in their lifetimes. Foster is especially clear:

A succession of DUP leaders also dismiss the prospect of unification. Both Arlene Foster and Jeffrey Donaldson insist that they would not see a border poll or a united Ireland in their lifetimes. Foster is especially clear:

the test for a border poll is that people would vote for it in a majority. And there's no evidence of that. Yes, people can have different opinion polls, but there's no tangible evidence if you look right across Northern Ireland. - (Gordon, 2020; Crisp, 2023).

Current DUP leader Gavin Robinson rejects as a “tired lie” any talk of impending victory for Irish unity (Rice, 2025). Former DUP advisor Lee Reynolds contends that “demands for a referendum were always more cosplay than reality” (Reynolds, 2025).

Alliance’s position on the imminence of Irish unity is typical of its avowed stance on all constitutional issues: neutrality and agnosticism.[3] Party leader Naomi Long says it’s difficult to know whether the north is any closer to a border poll now than it was at the time of the GFA in 1998, and calls for the Secretary of State to clarify the goalposts for ordering a unification vote. Long, then, does not so much deny prevailing weather patterns as disclaim any capacity to ascertain which way the wind is blowing. But she’s not too concerned about her incapacity: constitutional questions are not now and never have been a priority for her party (Young, 2025).

Unionist commentator Alex Kane argues that Irish unity “isn’t coming any time soon” (Kane, 2025a). He goes beyond Long’s know-nothingness to declare that “here we are, 27 years on [from the Good Friday Agreement], and unity seems no closer than it was in 1998.” And he suggests that nationalist are irritated because “the polling numbers ... have yet to provide demonstrable evidence of a comfortable majority in favour of uniting Ireland any time soon” (Kane, 2025b). Sam McBride agrees that “there is no immediate prospect of a majority for Irish unity”, and like Taoiseach Martin, says that the proposal to hold a border poll in 2030 “isn’t serious” (McBride, 2023 & 2024). In McBride’s latest articles, the improbability of a border poll becomes such an ingrained assumption that he relegates it to subordinate clauses and deems it unworthy of substantive comment (McBride, 2025b, 2025c & 2025d).

Many scholarly analyses also assert that a northern majority for a united Ireland is not inevitable, and is certainly not around the corner. On the one hand, the amount of ink spent on demolishing the thesis of inevitability—a specious argument that no one, not even Sinn Féin, takes seriously—is becoming tiresome. On the other hand, critiques of inevitability do underline the important conclusion that demographic change on its own will not produce or prevent a united Ireland, a point powerfully made by Paul Morland and Paul Nolan, among others (Riley, 2023; Nolan, 2024).

Pro-union academics Colin Coulter and Peter Shirlow say that the civic nationalist group Ireland’s Future provides “little discernible logic” for “specifying 2030 as the ‘right time’ to hold a constitutional referendum.” They conclude that “the alchemists of constitutional change” seem to have selected that date for propaganda purposes, “to rally spirits at a time when opinion polls indicate that support for Irish unification has stalled” (Coulter & Shirlow, 2024). Coulter in particular is insistent that the main and perhaps only interpretation of recent opinion polls must be that more people support staying in the UK than support moving to a united Ireland. The “high levels of support for the status quo” must be the headline. For Coulter, any talk of increased support for Irish unity, even if the survey data appear to show it, is part of a “miserable monotone” that is “counter-intuitive” and “wrong-headed”(Coulter, 2024). His colleague Shirlow agrees, saying that “the commentary and political discourse [that] claims there is a trajectory towards Irish unification” are “wearied analyses of Northern Irish society” (Shirlow, 2025a). The implication is that advocates of Irish unity might consider stifling this kind of talk because pro-union academics find it so offensive.

There is, then, fairly broad agreement—except for obviously misguided, hopelessly obtuse and increasingly bothersome enthusiasts of Dublin rule—that a majority for Irish unity isn’t happening soon, and may not ever come about. Fair weather is ahead for supporters of continued union with Britain. But is that what the forecast unequivocally shows? I think not.

Poll of Polls

Philip McGuinness recently reviewed all the northern reunification polls since Brexit that are collated on Wikipedia. The website features polls from various sources, including the Northern Ireland Life and Times (NILT) surveys, LucidTalk, University of Liverpool, ARINS-Irish Times, Lord Ashcroft, and Ipsos Mori (Wikipedia, no date). McGuinness asked if the polls allowed a firm conclusion about the direction of constitutional travel: is continued union or Irish unity to be the north’s future. He answered that: “Opinion poll interpretation, like beauty, lies in the eyes of the beholder” (McGuinness, 2025).

The weather deniers suffer from a kind of statistical-political myopia that severely limits the poll results they are capable of beholding. In McGuinness’s study, all but one of the post-Brexit surveys show that the number of respondents favouring continued union exceeds the number backing Irish unity. This result is the only one the deniers observe. But there are other, equally legitimate, interpretations of the survey data. The preponderance of McGuinness’s evidence suggests that support for union is decreasing and support for unity increasing.[4] Of his 10 graphical presentations, six show that union’s lead over unity is narrowing, only three find the constitutional gap widening, and one shows no change. Some of his models that extrapolate from current trends in constitutional opinion predict that a united Ireland will gain over 50 percent support in the next year or two. To be sure, no one—including Philip McGuinness—really expects a majority for unity so soon (McGuinness, 2024). Current trends may prove difficult to sustain and can in fact be interrupted or overturned. Some of those trends, nevertheless, suggest that a majority for unity may eventually materialize. His analysis taken in the round reveals how wrong are the many commentators who so confidently claim that there is not any opinion poll data showing an emergent majority for Irish unity. McGuinness’s forecast is many-sided, contradictory and uncertain, but it does not unquestionably anticipate the maintenance of the union in perpetuity. The bold assertion of “no evidence for Irish unity” is empirically indefensible, however ideologically comforting some may find it.

Assembling results from assorted public opinion surveys is a popular way of forecasting the north’s constitutional future. This “poll-of-polls” approach is, however, not without problems. The many methodological differences among the various polls—all of which have an impact on estimates of constitutional preference—confound the easy and meaningful comparison of poll results.[5] This is not to say that comparing different polls is a pointless exercise. As I examined above, it’s useful to know if the findings of different polls converge to a common conclusion, and to understand if current trends in opinion favour union or unity. But it is to say that comparison of different polls must proceed with caution.

Northern Ireland Life and Times

Analyzing the results of a single survey over time is an alternative or complement to the poll-of-polls approach. For most of the remainder of the paper, I’ll examine data from a single source, the annual NILT surveys that I’ve used in many previous posts. This series uses a (mainly) constant methodology and is therefore not plagued by the many differences in survey design that so complicate comparison in the poll-of-polls approach. But the NILT is bound to its own methodological flaws, and analysts need to be cautious in interpreting its findings.[6] This survey also allows for a more detailed look at the data that goes beyond the poll-of-polls’ focus on just the overall estimates of the number of people supporting union and unity. With the NILT, we can, for instance, examine the diverse social bases of recent changes in the constitutional preferences of the northern electorate.

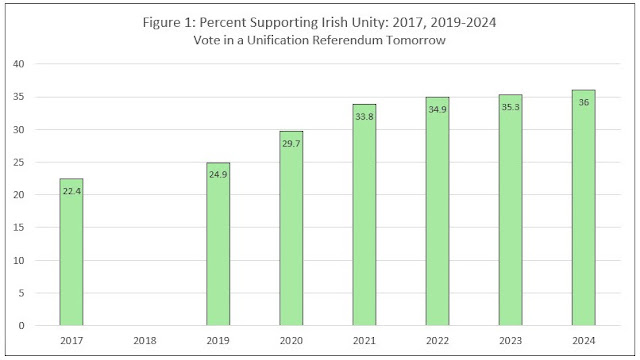

Figure 1 gives the percentage of respondents who say they would vote to unify with the rest of Ireland if a unification referendum were held tomorrow. The NILT started regularly to ask the unification referendum question in the post-Brexit period, although it was not part of the 2018 survey.[7] In calculating percentages, I use the full range of responses to the question including “don’t know”, but exclude those (very few) respondents who refuse to answer.

Alliance’s position on the imminence of Irish unity is typical of its avowed stance on all constitutional issues: neutrality and agnosticism.[3] Party leader Naomi Long says it’s difficult to know whether the north is any closer to a border poll now than it was at the time of the GFA in 1998, and calls for the Secretary of State to clarify the goalposts for ordering a unification vote. Long, then, does not so much deny prevailing weather patterns as disclaim any capacity to ascertain which way the wind is blowing. But she’s not too concerned about her incapacity: constitutional questions are not now and never have been a priority for her party (Young, 2025).

Unionist commentator Alex Kane argues that Irish unity “isn’t coming any time soon” (Kane, 2025a). He goes beyond Long’s know-nothingness to declare that “here we are, 27 years on [from the Good Friday Agreement], and unity seems no closer than it was in 1998.” And he suggests that nationalist are irritated because “the polling numbers ... have yet to provide demonstrable evidence of a comfortable majority in favour of uniting Ireland any time soon” (Kane, 2025b). Sam McBride agrees that “there is no immediate prospect of a majority for Irish unity”, and like Taoiseach Martin, says that the proposal to hold a border poll in 2030 “isn’t serious” (McBride, 2023 & 2024). In McBride’s latest articles, the improbability of a border poll becomes such an ingrained assumption that he relegates it to subordinate clauses and deems it unworthy of substantive comment (McBride, 2025b, 2025c & 2025d).

Many scholarly analyses also assert that a northern majority for a united Ireland is not inevitable, and is certainly not around the corner. On the one hand, the amount of ink spent on demolishing the thesis of inevitability—a specious argument that no one, not even Sinn Féin, takes seriously—is becoming tiresome. On the other hand, critiques of inevitability do underline the important conclusion that demographic change on its own will not produce or prevent a united Ireland, a point powerfully made by Paul Morland and Paul Nolan, among others (Riley, 2023; Nolan, 2024).

Pro-union academics Colin Coulter and Peter Shirlow say that the civic nationalist group Ireland’s Future provides “little discernible logic” for “specifying 2030 as the ‘right time’ to hold a constitutional referendum.” They conclude that “the alchemists of constitutional change” seem to have selected that date for propaganda purposes, “to rally spirits at a time when opinion polls indicate that support for Irish unification has stalled” (Coulter & Shirlow, 2024). Coulter in particular is insistent that the main and perhaps only interpretation of recent opinion polls must be that more people support staying in the UK than support moving to a united Ireland. The “high levels of support for the status quo” must be the headline. For Coulter, any talk of increased support for Irish unity, even if the survey data appear to show it, is part of a “miserable monotone” that is “counter-intuitive” and “wrong-headed”(Coulter, 2024). His colleague Shirlow agrees, saying that “the commentary and political discourse [that] claims there is a trajectory towards Irish unification” are “wearied analyses of Northern Irish society” (Shirlow, 2025a). The implication is that advocates of Irish unity might consider stifling this kind of talk because pro-union academics find it so offensive.

There is, then, fairly broad agreement—except for obviously misguided, hopelessly obtuse and increasingly bothersome enthusiasts of Dublin rule—that a majority for Irish unity isn’t happening soon, and may not ever come about. Fair weather is ahead for supporters of continued union with Britain. But is that what the forecast unequivocally shows? I think not.

The Forecast(s)

Philip McGuinness recently reviewed all the northern reunification polls since Brexit that are collated on Wikipedia. The website features polls from various sources, including the Northern Ireland Life and Times (NILT) surveys, LucidTalk, University of Liverpool, ARINS-Irish Times, Lord Ashcroft, and Ipsos Mori (Wikipedia, no date). McGuinness asked if the polls allowed a firm conclusion about the direction of constitutional travel: is continued union or Irish unity to be the north’s future. He answered that: “Opinion poll interpretation, like beauty, lies in the eyes of the beholder” (McGuinness, 2025).

The weather deniers suffer from a kind of statistical-political myopia that severely limits the poll results they are capable of beholding. In McGuinness’s study, all but one of the post-Brexit surveys show that the number of respondents favouring continued union exceeds the number backing Irish unity. This result is the only one the deniers observe. But there are other, equally legitimate, interpretations of the survey data. The preponderance of McGuinness’s evidence suggests that support for union is decreasing and support for unity increasing.[4] Of his 10 graphical presentations, six show that union’s lead over unity is narrowing, only three find the constitutional gap widening, and one shows no change. Some of his models that extrapolate from current trends in constitutional opinion predict that a united Ireland will gain over 50 percent support in the next year or two. To be sure, no one—including Philip McGuinness—really expects a majority for unity so soon (McGuinness, 2024). Current trends may prove difficult to sustain and can in fact be interrupted or overturned. Some of those trends, nevertheless, suggest that a majority for unity may eventually materialize. His analysis taken in the round reveals how wrong are the many commentators who so confidently claim that there is not any opinion poll data showing an emergent majority for Irish unity. McGuinness’s forecast is many-sided, contradictory and uncertain, but it does not unquestionably anticipate the maintenance of the union in perpetuity. The bold assertion of “no evidence for Irish unity” is empirically indefensible, however ideologically comforting some may find it.

Assembling results from assorted public opinion surveys is a popular way of forecasting the north’s constitutional future. This “poll-of-polls” approach is, however, not without problems. The many methodological differences among the various polls—all of which have an impact on estimates of constitutional preference—confound the easy and meaningful comparison of poll results.[5] This is not to say that comparing different polls is a pointless exercise. As I examined above, it’s useful to know if the findings of different polls converge to a common conclusion, and to understand if current trends in opinion favour union or unity. But it is to say that comparison of different polls must proceed with caution.

Northern Ireland Life and Times

Analyzing the results of a single survey over time is an alternative or complement to the poll-of-polls approach. For most of the remainder of the paper, I’ll examine data from a single source, the annual NILT surveys that I’ve used in many previous posts. This series uses a (mainly) constant methodology and is therefore not plagued by the many differences in survey design that so complicate comparison in the poll-of-polls approach. But the NILT is bound to its own methodological flaws, and analysts need to be cautious in interpreting its findings.[6] This survey also allows for a more detailed look at the data that goes beyond the poll-of-polls’ focus on just the overall estimates of the number of people supporting union and unity. With the NILT, we can, for instance, examine the diverse social bases of recent changes in the constitutional preferences of the northern electorate.

Figure 1 gives the percentage of respondents who say they would vote to unify with the rest of Ireland if a unification referendum were held tomorrow. The NILT started regularly to ask the unification referendum question in the post-Brexit period, although it was not part of the 2018 survey.[7] In calculating percentages, I use the full range of responses to the question including “don’t know”, but exclude those (very few) respondents who refuse to answer.

Figure 1 shows that support for Irish unity is trending upwards, with the number of respondents favouring a united Ireland growing each year. Many of the year-to-year increases are within the surveys’ margins of error (approximately ±2.8 percent) and are therefore not statistically significant. But the level of support for Irish unity since 2021, in the mid-30 percent range, is significantly higher than it was in 2017 and 2019, when support was between 22 and 25 percent. Over the entire period, the numbers backing unity grow by 13.6 percentage points. The 36 percent favouring a united Ireland in 2024 is the highest the NILT has ever recorded.

Figure 2 shows corresponding data for the percentages supporting continued union with Britain. The numbers favouring union are trending downwards, with support since 2021 significantly lower than it was in the earlier post-Brexit period. Across all the years in the figure, support for union declines by 12.2 percentage points. The proportion of respondents backing union in 2024, at just 42.5 percent, is an historic low in the NILT series, and it is less than the level of support recorded in any of the polls on Wikipedia that McGuinness analyzes.

Figure 3 presents support for both unity and union in a single chart, and uses a different format to facilitate uncovering certain patterns in constitutional opinion. Four such patterns appear. First, union always receives more support than does unity: in each year the circular orange data points are above the green squares. Second, the steepest drop in support for union and steepest rise in support for unity occur in the early post-Brexit years, from 2017 to 2021. Third, from 2022 to 2024, union’s decline and unity’s ascent are more gradual. Fourth, levels of public support for union and unity are converging: the orange circles and green squares get closer together over time. In 2017, for example, support for union stands at 54.7 percent, for unity at 22.4 percent, which gives a net preference for union of 32.3 percentage points. By 2024, the gap between the two constitutional options shrinks to just 6.5 points, 42.5 percent for union and 36 percent for unity. Significant change is, however, not confined to comparisons between the immediate post-Brexit period and the here and now. Examining the two most recent surveys in 2023 and 2024 shows that union’s advantage over union is cut almost in half in a single year. Convergence continues.

All these trends for the variable “vote in a unification referendum tomorrow” are confirmed by an analysis of the variable “long-term constitutional preference”, which asks respondents what they think the long-term policy for Northern Ireland should be. Long-term constitutional preference is an especially useful variable because the NILT measures it in every survey since the series began in 1998. Standing back to take an extended view of trends in constitutional opinion clarifies what’s happened since Brexit.

Figure 4 tracks support for union and unity since 1998. To facilitate comparison, it has lines connecting the data points of each constitutional option. Prior to 2007, the NILT asks respondents to choose between two long-term options: to remain part of the UK or to reunify with the rest of Ireland. From 1998 to 2006, then, the figure has two lines tracking support for union (orange) and unity (green). Starting in 2007, the NILT uses a revised question that splits the union option into two separate response categories: “remain part of the UK with direct rule” or “remain part of the UK with devolved government”. I’ll say more about this question later on; for now, let me continue with the format of Figure 4. The revised question means that, from 2007 to 2024, the figure has four separate lines representing (1) support for union with devolution in red; (2) support for union with direct rule in blue; (3) total support for union in orange, which simply sums the percentages for devolution and direct rule; and (4) support for unity in green.

There’s a lot going on in Figure 4. Let me concentrate on just a few aspects. The measure of long-term constitutional preference shows—as did the measure of vote in a unification referendum tomorrow—that union (orange) is always a more popular choice than is unity (green); that, since 2016, union is trending steadily downwards and unity upwards; and that the gap in popular support between these alternative northern futures is narrowing. The figure also demonstrates the historic nature of recent changes, and confirms Brexit as a watershed event that helped fundamentally to restructure the distribution of constitutional beliefs in the north. Support for unity is currently at its highest level ever in the NILT series that stretches back to 1998, and support for union is at an all-time low. Finally, Figure 4 shows that by 2024, there is little to choose between the 34.1 percent of respondents favouring union with devolution (red) and the 31.7 percent backing Irish unity (green). In fact, this small difference is within the surveys’ margin of error, so the proper and precise conclusion is that there is no statistically significant difference in support for these two constitutional options. All the 2024 difference between total support for union (orange) and support for unity (green) is due to the rump of respondents who favour union with direct rule from Westminster (blue). These respondents consistently represent just over 10 percent of the northern electorate, are disproportionately Protestant and unionist, and are completely out of touch with the power-sharing arrangements that have structured governance initiatives in the north for over 50 years. Plurality support for maintenance of the union is in extremely unrepresentative hands.

Let’s return to the variable “vote in a unification referendum tomorrow”, and to the main question of the constitutional forecast for the north in the post-Brexit period. Figure 5 provides the information needed to predict the north’s future based on current trends in constitutional opinion. It reproduces the data points of Figure 3 showing support for union and unity since 2017, but adds linear trend lines for each constitutional alternative. The trend lines summarize the pattern in the data points. More precisely, they measure the linear relationship between time (on the horizontal axis) and constitutional opinion (on the vertical axis). Further analysis shows that the lines are a very good “fit” for the data: the orange data points cluster closely around the line for union, as do the green data points around the line for unity.[8] Figure 5 confirms our earlier (and more casual) observations about constitutional trajectories. The orange line has a negative slope, indicating that support for union is trending downwards over time. The green line has a positive slope, showing that support for unity is trending upwards over the period. The slope of the unity line is a little steeper than is the slope for union, meaning that on average support for unity is rising faster each year than support for union is falling.

The usefulness of the green trend line is that we can project it into the future to predict when a constitutional majority for Irish unity might emerge by noting at what point the line crosses the threshold of 50 percent support. This kind of projection assumes, of course, that the current linear trend will persist. Extending the green line into the future reveals that a 51 percent majority for a united Ireland will appear by February 2030.

Figure 6 reveals that, once again, the measure of long-term constitutional preference confirms the trend just observed for the measure of vote in a unification referendum tomorrow. Note that the estimates of support for Irish unity using long-term preference are always lower than are the estimates for vote tomorrow. This pattern is to be expected as the long-term preference question is probably biased in a way that systematically underestimates support for reunification (Burke, 2021).[9] In any event, the trend line for long-term preference forecasts the same constitutional outcome. Extrapolating into the future from the black line for long-term preference suggests that a 51 percent majority for unity will surface by January 2033. The appearance of a majority is a little delayed, when compared to vote tomorrow, because the overall estimates for unity are lower and because support for unity is growing at a slightly lower average yearly rate.

Intense debate about the north’s constitutional future erupted most recently with the publication of the latest ARINS-Irish Times survey showing a 7 percent increase over just two years in the number of people who would vote for Irish unity in a unification referendum. Support for a united Ireland grows from 27 percent in 2022 to 34 percent in 2024. Coulter argues that a large part of the increase represents not real change in constitutional preference but methodological inconsistencies in the survey design. The principal investigators (PI) of the ARINS-Irish Times surveys—John Garry, Brendan O’Leary, Jamie Pow and Dawn Walsh—contest Coulter’s conclusions. Both sides in the debate produce revised estimates of support for union and unity based on different methodological assumptions.[10] From the perspective of forecasting the north’s constitutional future, these various revisions make only marginal difference to the calendar predicting a majority for Irish unity.

Table 1 pulls together the various ARINS-Irish Times forecasts and puts them alongside the NILT projections. I generated the ARINS-Irish Times predictions using the same linear trend model described above. The forecasts show a 51 percent majority for Irish unity emerging as early as November 2028 or as late as January 2033. Whatever timetable we use, majority support for a united Ireland appears to be on the horizon. There is, then, empirical substance to the pro-unity trajectory that unionists dismiss as a “tired lie” or “cosplay”. And it’s social science rather than alchemy that fuels the contemporary upsurge in advocacy of a united Ireland that pro-union academics delegitimize as a “miserable monotone” or “wearied” analysis.

The type of forecasting summarized in Table 1 comes with a number of important caveats. As McGuinness notes, it takes a “brave person” to forecast the future from the results of just one or two polls (McGuinness, 2025). Garry et al. caution that the three data points from the ARINS-Irish Times surveys in 2022, 2023 and 2024 are not a sturdy basis for confident prediction (Garry et al., 2025a). The same kind of caution applies to the NILT forecasts, even though I use seven and eight data points, depending on whether I’m predicting from the referendum tomorrow variable (seven) or the long-term preference measure (eight). The need to be careful stems from the truism that any forecast is only as good as the next data point: the prediction of a sunny day is overturned by the arrival of rain. For the various forecasts in Table 1 to remain accurate, popular support for Irish unity would have to increase by an average of 2 to 3.5 percentage points per year. Maintaining this annual rate of growth will prove daunting. The next few results from the annual NILT surveys may completely upend the trends on which my forecasts are based. They may show that a linear trend no longer holds, or that an upward or downward trajectory flatlines or reverses.

Even with these caveats in mind, I’ve copied Table 1 to my smartphone to show to anyone repeating the nonsense that there is “no evidence” that a pro-unity majority is coming. Current trends in opinion are, after all, still among the best information available on which to base forecasts about the north’s constitutional future. And analysts have long been using them for just that purpose, as in John Coakley’s 2007 projection that “it is extremely unlikely, on the basis of present trends, that a majority in Northern Ireland will ever vote for Irish unity” (Coakley, 2007, p. 592). Trends have changed, and so too must the forecast.

The Social Content of Changing Constitutional Preference

In this section, I use the NILT surveys to demonstrate the social robustness behind the forecasts of a trajectory towards a united Ireland. The recent momentum benefitting Irish unity over continued union cuts across diverse social categories. The once stark asymmetry distinguishing almost unanimous Protestant support for union from middling levels of Catholic support for unity has abated considerably. And the portrait of “Neithers”—those who say they think of themselves as neither unionist nor nationalist—as firmly in the union camp is seriously out of date.

Table 2 shows group changes in support for unity and union between 2017 and 2024. It examines groups defined by religion, political identity, national identity, party support, sex, age and occupational status. The last row reminds us that, for all respondents, support for unity increases by 13.6 percentage points over the period, and the number backing union declines by 12.2 points, as we initially saw in Figures 1 and 2. This overall pattern of change is reproduced at group level. Support for unity grows in all 27 groups arrayed in the table; support for union falls in 26 of them, with Northern Irish being the sole exception. The percentages for those identifying as Irish, British or Northern Irish are in parentheses because they track changes between only 2017 and 2023. No comparable measure of national identity is available in the 2024 NILT survey.[11]

The resounding message of Table 2 is that the trend favouring unity over union is not confined to a few select groups, but is socially ubiquitous. It is, nevertheless, useful to highlight certain shifts in constitutional opinion. First, some groups exhibit considerable change favouring a united Ireland. Catholic support for unity rises from 49.3 percent in 2017 to 68.5 percent in 2024, an increase of 19.2 percentage points. Respondents with an Irish identity (+20.7) and those aged 18 to 24 (+17.8) also move especially strongly towards Irish unity over the relevant period. Changes in the constitutional opinion of young people are particularly noteworthy. In 2024, fully 47.5 percent of the youngest cohort

favours a united Ireland, the highest level of youth support ever recorded on the unification referendum question, and much higher than the cohort’s support for union, which sits at just 29.5 percent. On the measure of long-term constitutional preference, 2024 marks the first time since the NILT series started in 1998 that more young people opt for unity (35.7%) over union (31.7%). This structure of change in the north’s youngest voters must be especially disheartening for supporters of the union. Table 2 also demonstrates that some groups move significantly away from the constitutional status quo. Support for continued British rule among SDLP voters is cut in half, from 34.7 percent in 2017 to 16.5 percent in 2024, a decline of 18.2 points. Similarly, the group in intermediate occupations (-24) and small employers and own-account workers (-26.5) show much higher than average movement away from voting for union in a referendum.

Let me also say a few words about “middle-ground” groups. Many commentators note that the middle ground will play a crucial role in the outcome of any border poll. I’ve argued elsewhere that the conventional understanding of the middle ground in the north is highly problematic, but it’s nevertheless accurate to say such groups will prove influential in a constitutional vote. Nationalists and unionists by themselves cannot win the day; they will need help to swing the result their way. Table 2 reveals that, for all supposedly middle-ground groups except the Northern Irish, the magnitude and direction of recent changes unequivocally favour a united Ireland. Many more people in the middle ground support unity now than did in 2017, and many fewer favour continued union. The change statistics tell the story: Alliance supporters are +16.5 points for unity and -20.7 points for union, the no religion group is +22.7 and -10.6, and Neithers are +11.6 and -12.9. Even though each of these groups continues to favour union over unity in 2024, the gap between the two constitutional options is rapidly closing. The change data for the Northern Irish—showing slight movement towards both union (+4) and unity (+2.3)—are distinct from those of other middle-ground groups. This peculiarity is not surprising: the Northern Irish are not part of the middle ground, however understood, because their social profile is increasingly Protestant and unionist (Burke, 2024).

The constitutional views of Catholics, Protestants and Neithers warrant further analysis because they continue to feature prominently in conversations about the north’s future. Coakley often comments on the asymmetry of northern Protestant and Catholic opinions on the constitution: the proportion of Protestants backing union is much higher than is the proportion of Catholics favouring unity (Coakley, 2007, 2015 & 2020). This asymmetry partly explains both his 2007 prediction, quoted earlier, that a northern majority for Irish unity is “extremely unlikely” to materialize, and his more recent conclusion that “[t]here is little in these data ... to suggest that Northern Ireland is on the verge of a pro-unity majority” (Coakley, 2020, p. 5). In the recent controversy over the ARINS-Irish Times surveys, Coulter deploys the asymmetrical argument, claiming that constitutional change is implausible partly because the large discrepancy between Protestant near-unanimity on union and Catholic disagreement on unity has not changed (Coulter, 2025a). Shirlow looks at the obverse side of asymmetry, noting: “Survey after survey shows more Catholics wish NI to remain in the UK than Protestants want a united Ireland” (Carroll, 2024).

Figure 7 demonstrates that Protestant/Catholic constitutional asymmetry changes markedly in just seven years. In 2017, 85.3 percent of Protestants say they would vote for union in a referendum while 49.3 percent of Catholics would back unity. This gap of 36 points falls each year, reaching a low of just 5.3 points in 2024. The gap closes both because of a drop in Protestant support for union and a rise in Catholic support for unity, with the latter factor doing most of the work. Coulter, then, is simply wrong to say that Protestant and Catholic constitutional asymmetry has congealed in its heavy pro-union disposition. Figure 7 shows steady movement towards convergence, not continued discrepancy.[12] Looking at the other side of asymmetry reveals that the pattern Shirlow identifies no longer holds. NILT data from 2024, which are not part of the figure, show that the number of Catholics supporting union (9.8%) and the number of Protestants supporting unity (9.9%) are identical. The constitutional preferences of Protestants and Catholics are no longer asymmetrical but balanced.

To appreciate the enormity of changes taking place in recent years, we can look back to Coakley’s summary of the social, political and constitutional landscape between 1968 and 2012:

Protestants tend to identify overwhelmingly as unionist (or as neither unionist nor nationalist; but never as nationalist), as British (or as Ulster or Northern Irish; but rarely as Irish) ... and they overwhelmingly support the union (with only a tiny portion endorsing Irish unity). These attitudes are not reciprocated on the Catholic side. Catholics identify as nationalists, but not as strongly as Protestants do as unionists; they see themselves predominantly as Irish, but a sizeable proportion opt for British identity... But their attitudes towards the constitutional question show the starkest contrast between the solidity of the two sides: in recent surveys, pro-union Catholics have outnumbered those favouring Irish unity (Coakley, 2015, p. 48).

These social correlates of constitutional opinion have been completely upended, to the advantage of Irish unity. Now, Catholics identify as nationalists (68.5% in 2024) as strongly as Protestants identify as unionists (65.7%); they still see themselves predominantly as Irish (68.6% in 2023), but only 3.2 percent opt for British identity; and pro-unity Catholics (68.5% in 2024) heavily outnumber those backing maintenance of the union (9.8%).[13] The weather is changing.

Finally, let me examine the Neithers, who describe themselves as neither unionist nor nationalist. I’ve already mentioned this group briefly as one important component of the north’s “middle ground”. But they deserve special consideration because the constitutional inclination of Neithers often arose in the heated dispute over the estimates of support for union and unity in the ARINS-Irish Times surveys. That debate cited the studies of Katy Hayward and Cathal McManus (2019) and Jon Tonge and Thomas Loughran (2024) as the definitive word on what Neithers think about the north’s constitutional future. These two influential studies are not definitive, but are an unfortunate combination of being wrong, instantly outdated and anomalous—all of which gives a misleading portrait of the recent constitutional journey of Neithers.

Hayward and McManus make an egregious error in describing the evolution of constitutional opinion among Neithers. Looking at the NILT’s measure of long-term constitutional preference between 1998 and 2017, the authors say: “There has not been any dramatic change since 1998 in the spread of support among Neithers for the various options on the constitutional question” (2019, p. 149). This statement is simply wrong. Neithers’ constitutional beliefs changed dramatically between 2005 and 2007. Their preference for Irish unity almost doubled from 2005 to 2006, rising from 16.5 percent to 28.1 percent. Just a year later, in 2007, that support declined by 9.9 points to 18.2 percent, their backing of union increased by 18.7 points to 65.5 percent, and their “don’t know” responses fell by almost two-thirds to 7.1 percent. These years witness great volatility not stability in the constitutional opinions of Neithers. I’ve suggested above and shown elsewhere that such big changes in 2007 are probably the result of systematic measurement error in the survey’s revised question measuring long-term preference. Hayward and McManus are not compelled to offer any explanation of what happened to the constitutional beliefs of Neithers because they write as if such rapid and drastic changes did not occur.

The authors are also a bit unlucky. Their portrait of Neithers is undergoing substantial transformation as they write. On Neithers’ steady and strong constitutional preference between 2007 and 2017, Hayward and McManus conclude: “Devolution within the United Kingdom is consistently the favoured outcome – generally three times more so than Irish unification” (2019, p. 149). This ratio in favour of union starts to change the moment they identify it in their 2019 article. In 2020, Neithers’ preference for union with devolution weakens and their backing of unity soars. By 2024, Neithers’ support for the two constitutional options converges, with devolution preferred to unity by only 28.6 percent to 24.8 percent. These figures are far removed from the three-to-one advantage in favour of devolution within the UK that Hayward and McManus find in the 2017 survey. In fact, from the time the authors wrote in 2019, Neithers’ net preference for union over unity plummets spectacularly. In 2019, a total of 63.6 percent of Neithers prefer union, either with devolution (41.3%) or with direct rule (22.3%), compared to just 14.1 percent in favour of Irish unity, a difference of 49.5 percentage points. By 2024, this net preference for union plunges to just 12.7 percentage points. The gap narrows because Neithers’ support for both forms of union—with devolution and with direct rule—falls while their support for a united Ireland rises.

Hayward and McManus are of course responsible for any errors they make in characterizing the constitutional beliefs of Neithers. But they shouldn’t be held accountable for bad luck. Rather, those commentators who continue to use Hayward and McManus’s obviously outdated data to say that, today, Neithers still heavily back union over unity—when this is patently untrue—should be called out for their partial and partisan approach to the survey evidence.

Likewise, current debates about the constitutional status of the north make very questionable use of Tonge and Loughran’s analysis of Neithers. In an exceptionally large survey conducted in 2022, the authors find that Neithers overwhelmingly prefer union to unity: a majority wish to remain part of the UK over the long term and less than one-fifth want to reunify with the rest of Ireland (Tonge & Loughran, 2024). Coulter and Shirlow constantly privilege this distribution of Neithers’ constitutional opinion, and enlist it as evidence supporting their conclusion that there is probably not any meaningful movement towards Irish unity (Coulter & Shirlow, 2024; Coulter, 2025b; Shirlow, 2025b). I disagree with their privileging and their conclusion.

Figure 8 shows the constitutional preferences of Neithers taken from various surveys in the two years before and after Tonge and Loughran’s 2022 study. Noticeable immediately is that the authors’ estimate of the number of Neithers backing union is by a considerable amount the highest of all the surveys, and their estimate of Neithers’ support for unity the lowest. The solid orange line shows that the Tonge-Loughran finding of 53.9 percent of Neithers favouring union is far above the surveys’ average of 43.8 percent. The dashed green line indicates that the authors’ estimate of 19.6 percent of Neithers backing unity is below the overall average of 24.4 percent. That is, the Tonge-Loughran findings seem anomalous, even though Coulter and Shirlow cite them as representative, if not archetypical.[14]

The other point to note about Figure 8 is that Neithers’ support for union falls and their support for unity grows in the two years after Tonge and Loughran’s result. The contrast between Tonge-Loughran in 2022 and the 2024 Northern Ireland General Election Study is especially interesting because Tonge is principal investigator on both surveys. The 2024 survey puts Neithers’ support for union at just 39.2 percent, almost 15 points below the estimate from Tonge-Loughran in 2022. And the same surveys show that support for unity among Neithers rises significantly by 5.6 points over the period.[15] In fact, the two surveys on which Tonge is principal investigator give fundamentally different views of the constitutional profile of Neithers and the state of the union. In 2022, the gap between Neithers’ support for union and their support for unity is fully 34.3 percentage points. By 2024, the gap in favour of union among Neithers is cut by almost two-thirds, to 14 points. If, as many suggest, the fate of the union is in the hands of the “middle ground”, the union is much less safe in 2024 than it was in 2022, and the Neithers’ direction of travel must be very troubling to supporters of the constitutional status quo.

This analysis suggests two reasons to avoid a heavy reliance on Tonge and Loughran’s findings: they seem to be an aberration and they cannot take into account how much Neithers’ constitutional opinions have changed since 2022. Participants in constitutional exchanges who foreground Tonge’s 2022 survey while they disregard his 2024 findings and other like results might justifiably be asked why they are ignoring the facts.

Conclusion: Do Constitutional Opinions Matter?

The survey results I’ve examined allow for different interpretations and different emphases, but only up to a point. Some views are way off the mark. Commentators who say there is no evidence of a trajectory towards Irish unity are clearly wrong. Naomi Long is mistaken to claim that we don’t know if the north is any closer to unity now than it was in 1998, as is Alex Kane to make the stronger assertion that the north is seemingly no closer. Coulter and Shirlow err in insisting that the only two allowable interpretations of recent constitutional opinion are the high support for continued union with Britain and the flatlining of the numbers backing Irish unity. These kinds of accounts no doubt reassure supporters of the union. And some analysts use them to belittle advocates of a united Ireland. Discarding the inclination to comfort unionists or mock nationalists unlocks alternative interpretations of the polling data that offer a more accurate and complete representation of the state of constitutional play.

In the entire NILT series of annual surveys from 1998 to 2024, the numbers backing union always exceed those favouring unity. All recent opinion polls but one show more popular support for remaining in the UK than for reunifying with Ireland. In this one sense, Coulter and Shirlow are correct. But there is more to the constitutional story than the authors’ constant reiteration of the high levels of support for the status quo. Those “high levels” are at the same time so low that they locate the north at the boundary of democratic illegitimacy (Burke, 2023). The Good Friday Agreement specifies that the democratic legitimacy of the north’s status as part of the UK “reflects and relies upon” the wish of a majority of its people (Constitutional Issues, sec. 1(iii)). The majority wish for union is evaporating. Only four of the 23 polls since 2021 put support for union at or above 50 percent. The 2024 NILT survey indicates that just 42.5 percent of respondents would vote to remain in the UK if a constitutional referendum were held tomorrow, which is a number well below the majority threshold the GFA identifies.

Current trends in public opinion are another part of the constitutional story, and they augur well for Irish unity. Support for a united Ireland is climbing and support for continued union dwindling. If those trends hold—and as I said that’s a mighty big “if”—unity does appear to be in the forecast. Even if we acknowledge that the biggest changes in constitutional preferences occur in the early post-Brexit years, we should understand Brexit as a profound interruption that helps cause a sea-change in opinions. The competition between alternative constitutional futures is much closer after Brexit than it was before, and is incrementally getting more competitive.

It’s important to step back from the contest between union and unity for majority public support to ask if the constitutional opinions of the northern electorate are of any significance at all. Many debates about what the polls indicate for the north’s constitutional future assume that changing popular preferences in favour of Irish unity will trigger the holding of a unification referendum. This assumption is unwarranted. The constitutional beliefs of citizens in the north don’t count, at least not directly. Majority support for Irish unity in opinion polls or election outcomes will not automatically culminate in a border poll.

The recent muddle over Fleur Anderson’s comments has ironically produced a “clarity” of sorts about the process of constitutional change. The Parliamentary Under-Secretary at the NIO suggested that the Secretary of State’s decision to call a unification referendum “would be based on opinion polls” (agendaNI, 2025). The DUP protested loudly that her remarks were “ill-considered” and “ill-judged”. The NIO immediately distanced itself from her statement (Cochrane, 2025). The ensuing debate was confusing and ill-informed. Participants noted that the GFA and Northern Ireland Act require the Secretary to call a border poll if he believes a majority in the north would support a united Ireland. Everyone, except Westminster and some unionists, took this legal obligation to mean that solid evidence of an emerging pro-unity majority—in social surveys or electoral outcomes—would compel the Secretary to act. Everyone, except Westminster and some unionists, is wrong. The Secretary has no mandatory legal duty to call a poll if a pro-unity majority exists.

The NIO, for good reason, continues to waffle, dissemble, evade and prevaricate. It’s understandably reluctant to articulate clearly its position on calling a border poll because that position is democratically untenable. But, between Hilary Benn’s response to Fleur Anderson’s comments and the NIO’s statement issued in clarification, an official position emerges: the Secretary of State will make “a political judgment” about whether there is majority consent to constitutional change (Campbell, 2025). And that determination is quintessentially political: the courts have ruled that it is not an empirical assessment based simply on pro-unity majorities in current opinion polls or recent election results (Burke, 2025). The Secretary of State will call a border poll when he is politically so moved, whatever that means. Unfortunately, the “clarity” emanating from the debate comes with an abundance of obscurity.

In essence, the one criterion for ordering a border poll is a remnant of imperialist arrogance. The British government, supported by British courts, has decided that a British Secretary of State will tell people in the north what they really think about the need for constitutional change. If the Secretary divines that the people want Irish unity, he’ll order a poll. If not, not. But he has the right to practise his constitutional sorcery quite independently of what people actually want. This criterion is a clear violation of a plain, ordinary and rational reading of the GFA. But that breach doesn’t matter. The British state decides what the GFA means for all its signatories, both British and Irish, from the north or south (McManus, 2025).

The current constitutional position, however idiotic, is that public opinion in the north might not play any direct role in determining the Secretary’s belief that there exists a majority for Irish unity. But the electorate’s preferences can nevertheless have an important indirect impact on constitutional developments. If the Secretary of State ignores repeated evidence of a pro-unity majority—which he is legally empowered to do—there will surely be a backlash. Many in the north and south will feel justifiably aggrieved, and this sense of grievance should help to mobilize a grassroots campaign to pressure the British government to order a border poll. The imperium does not often respond to polite requests based on democratic appeals to fairness or equality. It might respond to a determined political campaign with widespread popular and institutional backing.

Notes

[1] A Northern Ireland Office statement in February 2020 said:

It remains the Secretary of State's view that a majority of the people of Northern Ireland continue to support Northern Ireland's place in the United Kingdom and that this is unlikely to change for at least the foreseeable future. The circumstances set out in the Belfast Agreement that require the Secretary of State to hold a referendum on Irish unification are therefore not satisfied - (Kenwood, 2020).

[2] All direct quotations for which I do not cite a page or paragraph number are from internet documents that do not use a numbering system. Otherwise, I indicate the page or paragraph number of direct quotations.

[3] Alliance was a pro-union party from its inception in 1970 until 1999, when it changed party policy to become neutral on the constitution, in support of the GFA’s principle of consent (Tonge et al., 2024). I contend that, in practice, the party’s stated position of neutrality actually works to support maintenance of the union (Burke, 2024).

[4] FactCheckNI and Tonge have recently used the poll-of-polls approach and reached different projections. I prefer McGuinness’s study because it is both the most recent and the most statistically sophisticated. FactCheckNI looked at surveys from November 2017 to December 2022 and found that “polling over this period does not indicate a general increase or decrease in support for Irish Unity” (FactCheckNI, 2023). Tonge concluded that “A border poll, let alone a united Ireland, is not imminent based upon current polling evidence. There has been a moderately comfortable lead for supporters of the continuing union of Great Britain and Northern Ireland over those in favour of a united Ireland in every opinion poll conducted in 2021 and 2022” (Tonge, 2022, p. 19). Tonge also found that only four of 30 polls conducted between 2016 and 2022 show more support for Irish unity than for continued union, with one indicating majority support (52%) for a united Ireland (p. 18). As mentioned in the text of the paper, McGuinness found just a single poll showing plurality support for unity. McGuinness’s findings are more reliable than are those of Tonge. Three of Tonge’s polls depart significantly from the standard (but not identical) questions used to measure constitutional preference. Each of these polls mentions in the question a particular condition that likely affects how people respond. Two reference Brexit and one the NHS. The results from these atypical questions are not comparable to those from a more standard form of question. Likewise, a recent Amárach Research poll commissioned by European Movement Ireland found that 67 percent of people in the north would “support a united Ireland in the EU” (European Movement Ireland, 2025, p. 9). Again, this unusually high level of support for unity is no doubt influenced heavily by the nature of the question, and it should not be compared directly to other polls using more conventional measures of constitutional preference. Lord Ashcroft’s poll in fall 2019, cited by both Tonge and McGuinness, shows a slight but not statistically significant lead for unity over union, 46 percent to 45 percent. This survey uses a standard form of the border poll question and is therefore comparable to other surveys using the conventional format.

[5] Different surveys use different interviewing techniques, employ different sampling procedures, and compile their findings in different ways. Each kind of methodology influences the poll results (Doyle, 2022; Tonge & Loughran, 2024). Online surveys, for instance, tend to elicit fewer “don’t know” responses than do face-to-face surveys. Such methodological differences greatly complicate the interpretation of poll findings. When various surveys yield different estimates of the number of people supporting Irish unity, for instance, we need to ask how much of that difference represents real change in the public’s constitutional opinions, and how much reflects methodological variations in the design of the surveys. The unfortunate answer is that we often lack the information to differentiate “real change” from “methodological artefact.” By looking at many different polls, we multiply the number of methodological explanations that can serve as plausible alternatives to the explanation of real change. The “poll-of-polls” approach is largely oblivious to the confounding effects of methodological contamination. Its working assumption appears to be that all change is real change. This is clearly not the case. Taking into account the sampling error in the survey design further complicates the easy comparison of polls. Many of the differences in constitutional preferences that we see in the poll-of-polls approach are statistically insignificant. That is, they are differences that could reasonably occur by chance and do not necessarily represent real change in constitutional opinion.

[6] The NILT has over the years made some notable changes to its methodology. In 2007, it introduced a new measure of long-term constitutional preference, which I examine in this posting. In 2019, it changed its measure of vote intention in a unification referendum (see endnote 7). Occasionally, it makes changes to the series of questions measuring party support. In 2020, because of the pandemic, it altered its mode of interviewing from face-to-face to remote (online and video calls). This remote technique remains in place today (NILT, 2020).

John Doyle (2022) says that because NILT surveys consistently underestimate the number of Sinn Féin voters and overestimate Alliance voters, they should be used with extreme caution or not used at all for examining the constitutional preferences of the northern electorate. Not using NILT surveys is an extreme proposal that few analysts follow. But the surveys should be used with caution, for the reasons Doyle suggests and for other reasons I’ve mentioned in this and previous posts. See also the cautions regularly issued by Hayward and her co-authors, cited below. I think Doyle simplifies the explanation of why the surveys might not provide accurate representations of some parties’ voters, but that’s a discussion for another time perhaps.

The NILT political party variable asked in every survey since 1998 (but with slight variations in format) should not be understood as a simple measure of which party the respondent voted for in a recent election. It’s a more generic measure of political partisanship that attempts to gauge which party the respondent generally supports or feels closest to, which may be different from the respondent’s recent vote choice. That being said, estimates of party support derived from the NILT’s measure of generic partisanship do depart significantly from the number of votes that some parties received in recent elections. Using this comparison shows that recent NILT surveys continue the unrepresentative patterns that Doyle notes, but they also significantly underestimate DUP voters. In addition, the NILT does sporadically measure respondents’ vote in a recent election, and these measures reveal clear patterns of over- and under-representation of party voters in NILT surveys (Hayward & Rosher, 2020, 2021 & 2023; Hayward, Komarova & Rosher, 2022). Precisely how these inaccuracies affect estimates of constitutional preference, if at all, is not as obvious as Doyle seems to think.

[7] In 2017, the NILT question is: “If there was a referendum tomorrow about whether Northern Ireland should leave the UK and unite with the Republic of Ireland, how do you think you would vote? I would vote for Northern Ireland to remain part of the UK; I would vote for Northern Ireland to unite with the Republic of Ireland; I wouldn’t vote; or I don’t know” (NILT, 2017, p. M27). Since 2019, the reformatted question is: “Suppose there was a referendum tomorrow on the future of Northern Ireland and you were being asked to vote on whether Northern Ireland should unify with the Republic of Ireland. Would you vote ‘yes’ to unify with the Republic or ‘no’? Yes, should unify with the Republic; No, should not unify with the Republic; I would not vote; I am not eligible to vote; Other answer (please write in); I don't know; or Prefer not to say” (NILT, 2024, p. 76).

[8] R-squared is a statistic measuring goodness of fit. Generally speaking, the closer the line is to the data points, the better the fit. If every data point lies exactly on the line, the linear fit is perfect, and R-squared reaches its maximum value of 1.0 For the union line, R-squared=0.86; for unity, R-squared=0.91. That is, these are very strong linear trends.

[9] Given that the two variables measure different aspects of constitutional opinion—vote intention in a unification referendum tomorrow as opposed to long-term policy preference—we would expect the results to differ. But the precise way they differ lends credence to the hypothesis that the long-term preference question may be biased.

[10] Garry et al. (2025a) give the original ARINS-Irish Times estimates. In response to Coulter, the authors produce revised estimates based on “identical four-factor weighting” (Garry et al., 2025b). See Coulter (2024 & 2025a) for his first and second revisions of the ARINS-Irish Times estimates.

[11] In 2024, the NILT fundamentally changed the format of the question on national identity, making the new measure incompatible with the measure used from 1998 to 2023.

[12] The pattern in Figure 7 holds under different conditions, both if we use an alternative measure of Protestant and Catholic that is based on community background rather than religion, or if we use an alternative measure of constitutional preference based on what respondents think is the best long-term policy for the north rather than their vote intention in a referendum tomorrow. Coakley (2007) discusses the religious and community background/cultural measures of Catholic and Protestant.

[13] The percentages supporting unity and union are based on the measure of vote intention in a unification referendum. Coakley uses a different measure, long-term constitutional preference. Using the same measure as Coakley still shows that there are now many more pro-unity Catholics (60.3% in 2024) than there are Catholics favouring union (17.3%).

[14] Tonge’s 2019 Assembly election survey, which shows 52.9% of Neithers supporting union, closely aligns with his 2022 estimate. The NILT surveys in 2018 and 2019 (and before) are also more in line with Tonge’s 2022 result in that they show Neithers’ support for union is very high, at 59.8 percent and 63.6 percent, respectively. But the 2020 NILT poll goes on to document the beginning of a steep drop (to 45.3 percent) in the number of Neithers backing union, to which Tonge-Loughran is impervious. As Figure 8 shows, all the polls except Tonge-Loughran continue to record Neithers’ support for union in the mid-40 percent range until 2024, when it falls to just 37.5 percent. No matter how you look at the different surveys, the Tonge-Loughran 2022 result seems to be an anomaly.

[15] The margin of error for the 2024 Northern Ireland General Election survey is ± 3.1 percent. Assuming the same margin of error for Tonge-Loughran in 2022, we can say that the differences in support for both union and unity in the two surveys are statistically significant.

References

agendaNI. (2025). “Fleur Anderson MP: Calling border poll ‘would be based on opinion polls’” agendaNI 123 (April). Retrieved from.

Bain, M. (2023). “Border poll is not even on the horizon, says Starmer ahead of conference” Belfast Telegraph. 6 October. Retrieved from the Factiva (Dow Jones) electronic database of news articles [cited below as Factiva].

BBC. (2024). “Labour Party not prioritising border poll- NI minister.” 25 September. Retrieved from.

Breen, S. (2025). “Dublin can't keep ducking big decisions on Irish unity.” Sunday Life. 13 April. Retrieved from Factiva.

Burke, M. (2021). “Up with Union, Down with Unity: Measuring Constitutional Preference.” The Pensive Quill. 29 May. Retrieved from.

Burke, M. (2023). “The Crisis of Democratic Legitimacy in the North.” The Pensive Quill. 18 July. Retrieved from.

Burke, M. (2024). “The Inhabitants Of Middle Earth: Exploring The ‘Centre Ground’ In Northern Politics.” The Pensive Quill. 17 April. Retrieved from.

Burke, M. (2025). “Beguiling Constitutional Narratives 2: What Border Poll Criteria?” The Pensive Quill. 12 February. Retrieved from.

Campbell, N. (2025). “Referendum 'long way off' says Benn as unity poll row rumbles on.” Belfast Telegraph. 25 April. Retrieved from Factiva.

Carroll, R. (2024). “Prospect of Irish unification referendum remains remote despite Sinn Féin gains.” Guardian. 16 July. Retrieved from.

Coakley, J. (2007). “National identity in Northern Ireland: stability or change?” Nations and Nationalism 13:4 (October): 573–597.

Coakley, J. (2015). “Does Ulster still say ‘no’? Public opinion and the future of Northern Ireland.” In The Act of Voting: Identities, Institutions and Locale. ed. J.A. Elkink and D.M. Farrell, 25-55. London: Routledge.

Coakley, J. (2020). “Public Opinion and Irish Unity: Some Comparative Data.” PublicPolicy.IE: Evidence for Policy. 9 December. 6 pp. Retrieved from.

Cochrane, A. (2025). “DUP slams ‘disgraceful’ comments by NIO Minister who hinted Irish unity referendum decision would be ‘based on opinion polls’”. Belfast Telegraph. 22 April. Retrieved from.

Coulter, C. (2024). “The ARINS survey has some serious weight issues.” Slugger O’Toole. 8 November. Retrieved from .

Coulter, C. (2025a). “We need to talk about the ARINS survey on Ireland’s constitutional futures (PartOne)…” Slugger O’Toole. 11 March. Retrieved from.

Coulter, C. (2025b). “There’s still something not quite right about the ARINS survey: Part Two (Surveys & Elections).” Slugger O’Toole. 12 March. Retrieved from.

Coulter, C., and P. Shirlow. (2024). “Why facts (should) matter when it comes to discussing our political future…” Slugger O’Toole. 21 June. Retrieved from.

Crisp, J. (2023). “DUP leader: a united Ireland couldn't take my Britishness.” Sunday Telegraph. 22 October. Retrieved from Factiva.

Doyle, J. (2022). “Explaining the different results in opinion polls on Irish unity.” Royal Irish Academy. 12 July. Retrieved from.

European Movement Ireland. (2025). EU POLL 2025: Ireland and Northern Ireland. 8 May. Retrieved from.

FactCheckNI. (2023). “Is there no growth in public support for a United Ireland? Is support shrinking instead?” 30 March. Retrieved from.

Garry, J., B. O'Leary, J. Pow and D. Walsh. (2025a). “Trends show rise in support for Irish unity among Northern voters: Northern Protestants remain overwhelmingly against unity but show growing losers' consent.” Irish Times. 7 February. Retrieved from.

Garry, J., B. O'Leary, J. Pow and D. Walsh. (2025b). “Why the Critics of the ARINS•Irish Times Surveys are Wrong: A response to Professor Coulter.” Slugger O’Toole. 25 March. Retrieved from

Gordon, G. (2020). “Arlene Foster: I won't see a border poll in my lifetime.” BBC. 27 February. Retrieved from.

Hayward, K., M. Komarova and B. Rosher. (2022). “Political Attitudes in Northern Ireland after Brexit and under the Protocol.” ARK Research Update 147 (May). Retrieved from.

Hayward, K., and C. McManus. (2019). “Neither/Nor: The rejection of Unionist and Nationalist identities in post-Agreement Northern Ireland.” Capital & Class 43:1 (March): 139-155.

Hayward, K., and B. Rosher. (2020). “Political attitudes at a time of flux.” ARK Research Update 133 (June). Retrieved from.

Hayward, K., and B. Rosher. (2021). “Political Attitudes in Northern Ireland in a Period of Transition.” ARK Research Update 142 (June). Retrieved from.

Hayward, K., and B. Rosher. (2023). “Political Attitudes in Northern Ireland 25 Years after the Agreement.” ARK Research Update 151 (April). Retrieved from.

Kane, A. (2025a). “It’s going to be softly, softly, catchy monkey for Irish unity.” Irish News. 14 February. Retrieved from.

Kane, A. (2025b). “It’s Martin’s cannier approach to Irish unity that worries me.” Irish News. 18 April. Retrieved from.

Kenwood, M. (2020). “Requirements for vote on Irish unity have not been satisfied, city council told.” Belfast Telegraph. 22 February. Retrieved from Factiva.

McBride, S. (2023). “Viewed in the long arc of history, the scale of unionist decline is dramatic.” Belfast Telegraph. 22 May. Retrieved from Factiva.

McBride, S. (2024). “Where exactly are we going in the future? Northern Ireland politics in 2030 could look very different to how things are today.” Belfast Telegraph. 19 October. Retrieved from Factiva.

McBride, S. (2025a). “Dismissing a 2030 border poll, Taoiseach says uniting Ireland constitutionally is less important than building relationships.” Belfast Telegraph. 12 April. Retrieved from Factiva.

McBride, S. (2025b). ““How DUP has reacted to the death of Pope Francis is another sign of profound shift in NI life since Paisley era.” Belfast Telegraph. 26 April. Retrieved from Factiva.

McBride, S. (2025c). “SF gesture politics only tolerated so long as bigger picture of unity remains in sight: Republicans tiring of O'Neill's concessions, especially now as hopes of border poll fade.” Sunday Life. 27 April. Retrieved from Factiva.

McBride, S. (2025d). “Nationalists serious about unity should be cheering Nigel Farage's rise - he's their most likely route to a border poll.” Belfast Telegraph. 3 May. Retrieved from Factiva.

McGuinness, P. (2024). “Northern Ireland has a nationalist majority, but that doesn’t mean reunification will happen soon.” Irish Times. 28 August. Retrieved from.

McGuinness, P. (2025). “Can we see a direction of travel from polling on Remaining or Reunifying?” Slugger O’Toole. 24 February. Retrieved from.

McManus, S. (2025). “Reconciliation must not be used as a pretext for doing nothing.” Irish News. Letter to Editor. 28 May. Retrieved from.

NILT. (2017). Northern Ireland Life and Times Survey 2017: Main Questionnaire. Retrieved from.

NILT. (2020). Northern Ireland Life and Times Survey 2020: Technical Notes. 30 October. Retrieved from.

NILT. (2024). Northern Ireland Life and Times Survey 2024 Questionnaire (online). Retrieved from.

Nolan, P. (2024). “The Imprint of Finality? Partition and Census Enumeration.” Irish Studies in International Affairs. 35:2, pp. 23-55. Retrieved from

Paun, A., J. Sargeant and M. Fright. (2024). “Irish reunification: What is a border poll? What would happen if Northern Ireland and the Republic of Ireland voted in favour of reunification?” Institute for Government. 9 February. Retrieved from.

Reynolds, L. (2025). “One year on, what Gavin Robinson must do to take the DUP forward.” Irish News. 8 Apr. Retrieved from.

Rice, J. (2025). “Unity inevitable claim a 'tired lie', says Robinson.” Belfast Telegraph. 3 March. Retrieved from Factiva.

Riley, S. (2023). “'The demographics' in Northern Ireland will not deliver a united Ireland.” Belfast Telegraph. 5 July. Retrieved from Factiva.

Shirlow, P. (2025a). “ARINS: Is there a trajectory towards Irish unity? Probably not and that’s a good thing.” 9 April. Royal Irish Academy. Retrieved from .

Shirlow, P. (2025b). “Facts do not cease to exist because they are ignored. ― Aldous Huxley.” PowerPoint Presentation. Royal Irish Academy. 9 April. Copy of presentation received in a personal communication with the Royal Irish Academy.

Tonge. J. (2022). “How Close is a Border Poll or a United Ireland?” Political Insight 13:4 (December): 16-19

Tonge, J., and T. Loughran. (2024). “Beyond unionism and nationalism: do the ‘neithers’ want a border poll and a United Ireland?” Irish Political Studies 39:4, 594-616.

Tonge, J., M. Braniff, T. Hennesey, J.W. McAuley, C. Rice and S.A. Whiting. (2024). The Alliance Party of Northern Ireland: Beyond Unionism and Nationalism. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Wikipedia. (no date). “Opinion polling on a United Ireland.” Retrieved from

Young, D. (2025). “Alliance not taking position in border poll campaign may ‘make sense’, says Naomi Long.” Irish News. 27 February. Retrieved from

⏩ Mike Burke has lectured in Politics and Public Administration in Canada for over 30 years.

I don't give much credibility to these polls. Asking someone if they are in favour of a united Ireland, without having some idea of what a united Ireland might look like, and how much it will cost, seems fairly pointless to me. It's a bit like asking a resident on Falls Road, "Would you like a bigger house?" The answer will usually be "Yes I would!". Our resident will then ask, "Where is it?". If the answer is "Sandy Row", our resident might think again.

ReplyDeleteI think that's true about opinion polls but they work like that either way. If the question was to elaborate in terms of remaining in the UK with the effects of Brexit etc, the reluctance to stay might grow. Either way, there is no need to complicate a referendum - it is a simply question of stay or leave the UK. After it we an say 'the people have voted, the bastards.'

DeleteMike does great work on this type of stuff - very much a specialist subject with him. It is a very valuable resource to people interested in what is going on in relation to a border poll.

My own view is that there will not be one anytime soon - which is why it is a safe rallying call for SF to continue making. And with the behaviour of loyalism in Ballymena and during the hate fires, makes the SF demand attractive.