It is a striking portrait of an Army officer in number two dress uniform sat on a rock by a tree stump with the college behind him.

He is wearing three pips on each of his shoulders to denote the rank of Army Captain. On his right knee rests a peaked cap, complete with Grenadier Guards cap-badge.

The Grenadiers motto is Honi soit qui mal y pense, translated from the French as “Shame on anyone who thinks evil of it”, generally meant to point towards the evil intentions of the enemy.

There are two medal ribbons on the officer’s chest.

One is the General Service Medal (Northern Ireland clasp) and another is the George Cross (GC), the UK’s highest award for acts of heroism or courage in circumstances of extreme danger, other than those performed in the face of the enemy. It ranks alongside the Victoria Cross, which is the highest military award for valour and devotion to duty in the face of the enemy.

Below the portrait is an accompanying image, depicting the Guards officer perched in a photographer’s studio wearing full dress uniform, with a distinctive red tunic and bearskin headdress. In the middle of the mounted frame are miniatures of the officer’s medals and on the right of that is the citation for the GC, which was posthumously conferred upon him on 13 February 1978.

The inscription for the GC details the circumstances that led to the award.

It recounts a heroic struggle by the officer as blows reigned down on him from up to seven men, some who were members of the Provisional IRA.

The officer was then abducted and taken away to be tortured.

Despite the ferocity of the attack on him he refused to reveal anything to his captors.

|

| The author beneath the portrait of Captain Robert Nairac GC © Aaron Edwards |

I have taken several visitors to see the painting since I joined the academic faculty at Sandhurst.

Many have heard of the mythology surrounding the officer, Captain Robert Nairac.

I have even lectured Officer Cadets beneath Captain Nairac’s portrait, telling them something of his life and military service, including the personal qualities he displayed on the night he disappeared on 14/15 May 1977.

The GC citation lists these traits as ‘exceptional courage,’ including ‘acts of the greatest heroism in circumstances of extreme peril,’ which ‘showed devotion to duty and personal courage second to none.’

|

| The London Gazette carrying an announcement of the posthumous award of the George Cross to Captain Robert Laurence Nairac (Army Number: 493007) |

Who was Robert Nairac?

Robert Laurence Nairac was born on 31 August 1948 in Mauritius, off the coast of East Africa, to parents Barbara and Maurice. The family returned to the UK when Robert turned one, where his father, a doctor, took up a post in Sunderland.

The young Nairac was educated at Ampleforth, a Catholic public school, and later ‘went up’ to Oxford where he read Medieval and Military History at Lincoln College. While at Oxford in the late 1960s, he joined the Grenadier Guards as a University Cadet/Second Lieutenant on probation.

Upon completion of his studies, Nairac attended the post-University course at Sandhurst in September 1972, subsequently commissioning into the Grenadier Guards as a Lieutenant with seniority.

|

| Second Lieutenant Robert Nairac, centre row second from the right, with other members of the Sandhurst 1st XVs rugby team, 1972 © Wishstream Journal, RMAS |

Nairac’s first operational deployment was with Number 1 Company of the 2nd Battalion, the Grenadier Guards, in Ardoyne, north Belfast, from July through to October 1973.

One officer who served with Nairac at the time told a regimental historian: ‘Robert was fantastic with the Irish youth’ in Ardoyne, visiting the sporting club and introducing his comrade to the club committee where he ‘sang rebel songs with them, knowing more about Irish history than all of them.’

It was clear his first operational tour had a profound effect on him - he became enthralled by the people, the culture and the history of the place.

After the battalion returned to England in late 1973, Nairac volunteered for ‘Special Duties’.

In the spring of 1974 he attended and passed selection for the newly formed Special Reconnaissance Unit (SRU), which operated under a variety of cover names, including the Northern Ireland Training and Assistance Team (NITAT), 14th Intelligence Company and “the Det”. Nairac deployed to Northern Ireland on 21 May 1974.

According to one source, Nairac’s first appointment with the Det was as a Military Intelligence Liaison Officer (MILO) attached to 3 (Infantry) Brigade, the major tactical formation responsible for all military operations in South Armagh.

Nairac also served as a double-hatted MILO in the 8 (Infantry) Brigade area, responsible for the north of the Province later that year.

He returned to the Grenadiers in April 1975 and in June-July ran a course for NCOs in Pirbright, before deploying on exercise with his battalion on Salisbury Plain from mid to late July 1975. Nairac went on leave on 31 May 1975, travelling north to Scotland by road accompanied by his friend, Captain David Sewell. He subsequently attended the Junior Command and Staff (JCSC) course in early 1976.

Upon completion of the course Nairac volunteered to return as a MILO for 3 Brigade.

“Bandit Country”

In 1976 BBC Panorama aired a documentary on South Armagh, calling it by the name soldiers serving there had given it: “Bandit Country.”

It ran an interview with Lieutenant Colonel Philip Davies, the Commanding Officer of the Royal Scots. “The people are not friendly,” he told the reporter. “They are very clearly republican sympathisers… It is a region ‘under siege’ but we do need the people to cooperate.”

The documentary came in the immediate aftermath of the Provisional IRA massacre of ten Protestant workers in Kingsmills, not far from Bessbrook. British Labour Prime Minister Harold Wilson responded to the escalating sectarian conflict by authorising the deployment of the SAS.

When pressed about the government’s decision, Colonel Davies said he couldn’t comment on the specifics but added that “a particular role of theirs is covert surveillance which they’re very expert at.”

The Royal Scots were replaced by the 3rd Battalion of the Parachute Regiment (3 Para). Their Commanding Officer, Lieutenant Colonel Peter Morton, later wrote of the IRA that they were ‘easily the most successful in the Province,’ especially given their proven ability to kill or seriously injure members of the security forces.

Under the Freedom of Information Act (2000), I have secured the release of a number of declassified Top Secret intelligence dossiers on this period. These documents suggest that the South Armagh PIRA posed a considerable threat to the security forces in the mid-1970s.

They had demonstrated their ability to perfect new ways of killing soldiers and police officers.

IRA volunteers were designing and testing innovative new weapon systems, including various versions of the home made mortar, at an incredible rate.

By early 1977 British military intelligence discovered that the IRA in South Armagh had developed a brand new ‘heavy bomb’, consisting of 35lbs of commercial explosive in a makeshift warhead. Intelligence Officers warned how such a weapon ‘would have a far better chance of penetrating our defensive screens.’ While a previous version of this home-made mortar had been fired at Newry UDR camp and Bessbrook Mill with minimal impact, the IRA were proving capable of quickly adapting their deadly ingenuity to yield more death and destruction.

This extract from a recently declassified report gives a flavour of the emerging threat:

|

| Extract from a Military Intelligence Report, dated April 1977 © The National Archives, London |

MILOs in the 3 Brigade area would likely have been tasked with collecting as much intelligence on these highly destructive weapons as they could lay their hands on.

With attacks in South Armagh occurring almost every day, it is not difficult to appreciate the enormous task facing those, like Captain Nairac, who had previously been deployed in the intelligence war against the IRA.

What was Robert Nairac doing when he went missing?

There has been much speculation about what exactly Captain Nairac was doing on the night he went missing.

We know from his GC citation that he was based at Headquarters 3 Brigade and that his task on the evening he disappeared was ‘connected to surveillance operations.’

It is worth delving into the detail of how he came to find himself in such a perilous situation.

On 14 May 1977 Captain Nairac signed out of Bessbrook, according to the Ops Officer, Captain David Alan Collett (formerly of the Parachute Regiment), at 2125hrs and was scheduled to return by 2330hrs.

Nairac’s journey from Bessbrook Mill to his destination, the Three Steps Inn at Drumintee, took approximately 30 minutes.

We know from a statement Captain Collett subsequently gave to the RUC that Nairac radioed the Ops Room en route to Drumintee at 2148hrs, 2152hrs, 2156hrs and lastly at 2158hrs. In his final call, Nairac said he ‘would be closing communications and he indicated he had reached his destination, the Three Steps Inn.’

To say the rationale for Nairac’s visit to the Three Steps that evening is contested is an understatement.

John Parker, author of Death of a Hero: Captain Robert Nairac, GC and the Undercover War in Northern Ireland (1999), wrote at length about the risks Nairac took in 1976-77. He interviewed several of those who served with the SAS squadrons rotating into Bessbrook at the time.

Ken Connor was one of those SAS troops who had already gone on record in his memoir Ghost Force (1998) to complain about Nairac’s overconfidence and specifically how he ‘appeared to have been allowed to get out of control’ while becoming ‘lax about checking in with his base.’

This chimes with what another former soldier I interviewed told me about the rumours still floating around months after Nairac’s disappearance.

‘Nairac was a battalion Int Officer who fancied himself as a spy,’ he said. ‘He was a classic case of somebody who should have stuck to collating reports in his office.’

In the course of my own investigation into the abduction, murder and disappearance of Captain Nairac, I interviewed a former RUC Special Branch officer who told me he worked closely with him.

It’s fair to say he saw Nairac as a ‘loose canon’ and was convinced his superiors ‘weren’t aware of everything he was up to.’

The former SB officer I spoke to did concede that the Army was very much in charge in the border region at the time and so he could not have known the full inner workings of the military’s intelligence capability.

This widely-held view of Nairac as a ‘loose canon’ has gained considerable traction over the past five decades.

One man who did much to spread the myth was Clive Fairweather, a self-professed former member of the SAS.

Fairweather gave John Parker many of his insights into military and special forces operations in the late 1970s. According to Parker, Fairweather served as the G2 (Int) at HQNI at the time Nairac went missing.

In a chance encounter with former Provisional IRA member Anthony McIntyre at a prisons conference in Scotland in 2006, Fairweather referred to Nairac as “a stupid cunt.”

At this point it is worth mentioning that one SAS veteran I spoke to told me Fairweather had a penchant for embellishing his role in SAS operations, while minimising the actions of others.

This is certainly reflected in McIntyre’s incisive pen portrait of the man himself.

Nevertheless, I would contend that such a flippant view of Nairac as a ‘maverick fool with a death wish’, repeated by someone with perceived authority, is enough to do lasting damage.

When considered in conjunction with the Provisional IRA narrative about Nairac - discussed in Part 2 of this article - it became toxic.

It would not be seriously challenged until biographer Alistair Kerr published his well-received Betrayal: The Murder of Robert Nairac GC (2017).

In line with Kerr’s more objective account of Robert Nairac, it could be argued that the young captain was operating according to the conventions of military doctrine (essentially the military’s written compilation of best practice) at the time.

After all, the same doctrine, known as Counter-Revolutionary Operations (1969; republished in 1977), was widely distributed across the officer corps.

It reminded those involved in clandestine activity how ‘good liaison is of extreme importance,’ especially between G2 (Intelligence) and G3 (Operations), as well as with the local police Special Branch.’

It was Nairac’s job to build and maintain these key relationships between the newly arrived Special Forces toops, the regular soldiers and those locally recruited members of the RUC and UDR.

And it was no mean feat.

According to The Sunday Times Insight Team, Nairac ‘rightly believed that the key to British success against the IRA was good intelligence and he also believed that he could provide it on his forays out into the community.’

|

| The former British military base at Bessbrook Mill © Aaron Edwards |

It is clear that some RUC SB officers found Nairac easy to work with and dedicated to tackling paramilitary violence from whatever quarter.

‘It was almost as if what he was doing was a forerunner for the FRU [Force Research Unit, the British Army’s clandestine source handling capability established in 1980]'',’ a former Branchman told me.

Part-time source handling

If we accept the British government’s public acknowledgement that Captain Nairac was on duty the night he disappeared and that he was employed on ‘surveillance operations,’ it stands to reason he was performing an official military task.

As an Army officer who had recently passed JCSC, he would have been aware of the need to align his activities with what was known as ‘the higher commander’s intent’. At the time this was summarised according to the three-pronged strategy of reassurance, deterrence and attrition.

Operating at the interface of security forces operations was second nature to Nairac, after all he had previously completed two tours as a Det Liaison Officer.

From a document unearthed at the National Archives in London and published by researcher Tom Griffin on PowerBase we know that:

The prime task of the SRU is to conduct covert surveillance of terrorists as a preliminary to an arrest carried out by security forces in uniform. The SRU may also be used to contact and handle agents or informers and for the surveillance and protection of persons or property under terrorist threat. The SRU works to a great extent on Special Branch information and the Special Branch have a high regard for it.

There was even detailed guidance available to those officers responsible for clandestine counter-insurgency missions in Counter-Revolutionary Operations:

Good agents and informers, controlled by trained handlers, can be among the best sources of information, but failure to control and co-ordinate them, and the growth of private networks, will lead to compromise, false information and double agents - MoD, Counter-Revolutionary Operations.

Thanks to a recent investigation by Belfast Telegraph journalist Sam McBride we now know Nairac had likely gone to Drumintee ‘in the hope of meeting an informant.’

This complements John Parker’s earlier findings, where some of his SAS interviewees spoke of Nairac’s ‘part-time source handling.’

New revelations

In my own investigation into the case, I have come into possession of eyewitness statements given to the RUC, which detail Captain Nairac’s last-known movements.

They contain shocking new revelations, including how one eyewitness saw Nairac arrive at the Three Steps in his red Triumph not at 2200hrs as previously reported but 15 minutes after that time. He described both ‘the car and the person who was driving it’ as ‘strangers to me.’

What is significant about this sighting is not that Nairac arrived later than billed but that he arrived hot on the heels of two ‘well-dressed’ males in their early 20s.

They were seen being dropped off at the pub by a metallic grey coloured Ford Escort, which had come from the Newry direction and then drove off towards Forkhill.

Crucially, these two individuals had never been seen in the bar before.

They were described by several eyewitnesses inside and outside the premises as ‘strangers’.

As one eyewitness watched Nairac get out of his car and enter the bar he became fixated on something ‘unusual about the number plates’; ‘some of the numbers were covered in cement.’

When he walked over to the car for a closer look, he ‘saw a number of cigarette packets lying in the back seat,’ as if they had been furiously smoked by one person (or, perhaps, two people) who had been sat in the car for a long time.

The man thought no more about it.

At around 2330hrs the eyewitness said he saw three people go ‘up towards the top of the car park.’

Although it was ‘pretty dark at the time,’ he was ‘fairly sure that the three men were the same strangers who I had seen arriving earlier.’

To be continued in Part Two.

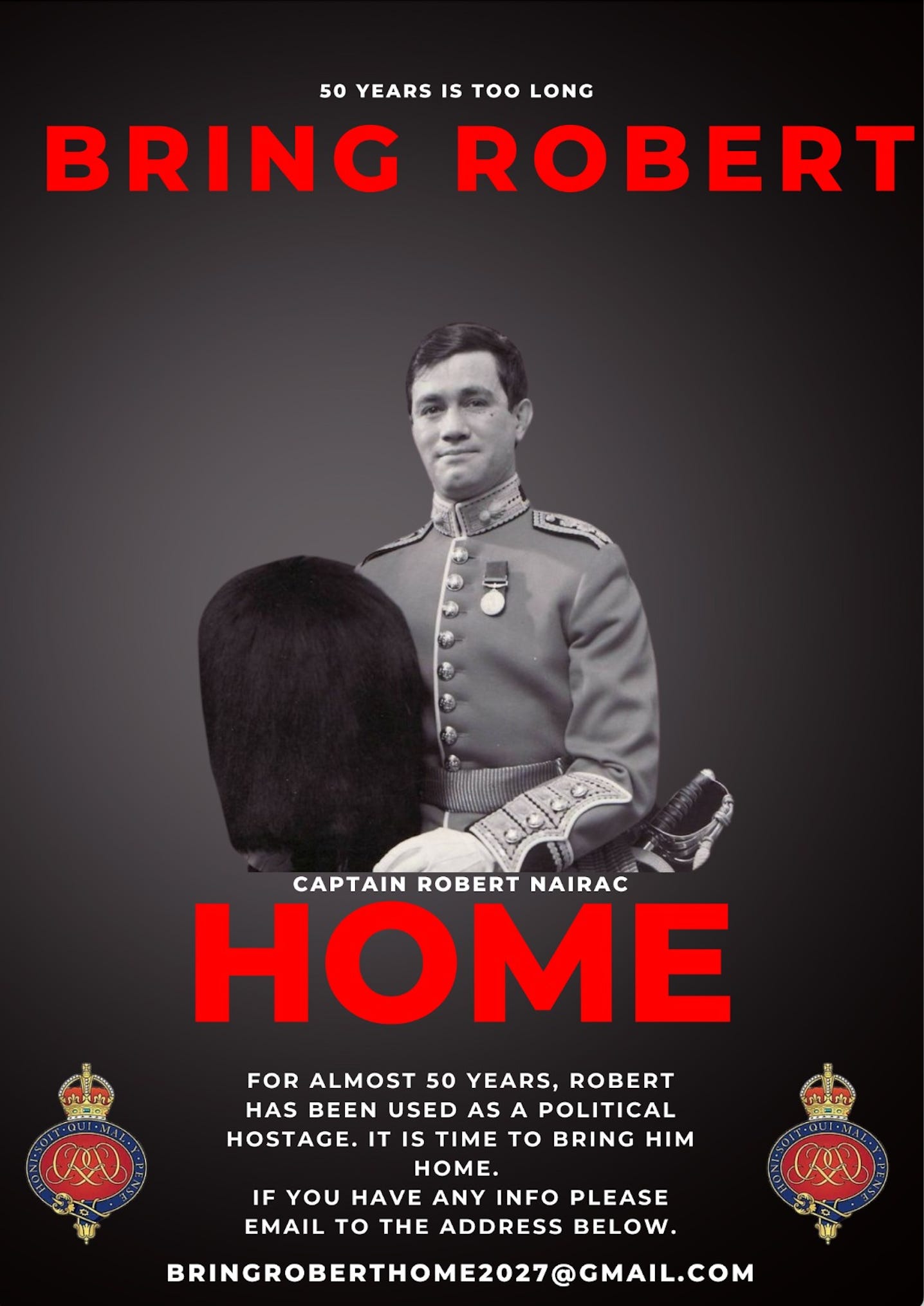

Appeal for Information

If anyone has any information about the abduction and murder of Captain Robert Nairac on 14-15 May 1977, please get in touch with the Bring Robert Home campaign via BringRobertHome2027@gmail.com. All correspondence will be treated with the utmost discretion.

The Bring Robert Home campaign is a loose network of veterans whose sole aim is to secure the return of Robert’s body to his family for a proper Christian burial, according to the customs of his Roman Catholic faith.

|

| © The Bring Robert Home Campaign |

⏩ Dr Aaron Edwards is an academic and Global Security expert.

Anyone from Belfast in particular and the North in general , will instantly pick someone trying to "put on" on our accent. It is impossible to imitate and fool a local. Let's call a spade a spade, his colossal arrogance cost him his life.

ReplyDelete