He is probably best known as the author of what many consider to be the outstanding novel written in Irish Cré na Cille, but he was also well known during his lifetime as a republican and Irish language activist.

He was also appointed as Professor of Irish in Trinity College which one commentator remarked was unusual for the fact that it this was at a time when the university was viewed with disfavour by the Catholic Church. With no reference of course to the fact that Catholics had not been allowed to become fellows or Professors until 1873.

Ó Cadhain’s politics have also been somewhat distorted. He is often referred to as being a Marxist, but there is no evidence that he was. Some commentators are prone to either conflate any social radicalism among republicans with Marxism, or in Ó Cadhain’s case to assert a sympathy on his part with totalitarian socialism that he did not evince during his own lifetime.

This is evident for example in a lecture given by Proinsias Mac Aonghusa on Máirtín Ó Cadhain – Poblactach agus Sóisialaí in 1989. Mac Aonghusa relies heavily on the evidence of former Communist Party leader Michael O’Riordan who was interned in the Curragh at the same time as Ó Cadhain during the 1940s. A much better understanding of Ó Cadhain and his time in the Curragh is found in the recollections of republican comrades rather than communists in Uinseann Mac Eoin’s The IRA in the Twilight Years.

Mac Aonghusa no reference to the fact that Ó Cadhain sided with the Liam Leddy group of prisoners who split from another group led by Pearse Kelly which included Communists who Kelly – who was similarly a radical republican who rejected Marxism – later expelled when they attempted to stir up dissension even among left inclined internees most of whom rejected the Communist attempt to suborn IRA Volunteers based on support for the Soviet Union. Nor had Ó Cadhain sided with those who took the side of the pro Soviet Republican Congress after the expulsion of Communist infiltrators from the IRA in 1933.

Ó Cadhain in common with many of those interned due to current or past associations with the IRA did not support the ill-conceived bombing campaign in England during World War II and later fell out with Leddy over the continued relevance of the IRA as a military organisation. Ó Cadhain believed that republicans needed to be at the centre of a broader movement focused on the economic, social and cultural problems of the country. Which was where Clann na Poblacta came from.

Indeed, far from being attracted to Soviet communism, the army intelligence service G2 reported in February 1945 that Ó Cadhain who had been released in July 1944 had, as part of his belief that the IRA as it then was no longer served a function, had apparently urged that “all arms remaining in the possession of the IRA should be handed over to hAiseirige” (R.M Douglas, Architects of the Revolution, p167, n.64)

Ailtirí na hAiséirighe were a militant nationalist group, which in some ways presaged the emergence of Clann na Poblachta, who supported Catholic social teaching and a more militant policy on the revival of Irish as a spoken language. They would be regarded as fascists by those leftists now claiming Ó Cadhain for their side. The Aiséirighe newspaper published several of Ó Cadhain’s prose works.

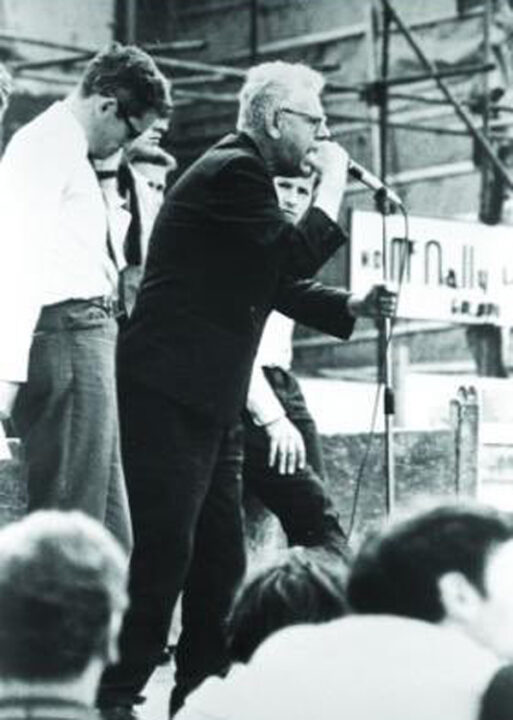

Ó Cadhain did not return to active work with the IRA following his release and apart from his rich literary output his later political activity focused on language rights, particularly within the Gaeltachts. Ó Cadhain had been involved in the 1930s with the first militant Gaeltacht movement, Muintir na Gaeltachta. The founding of Misneach in 1963 was a revival of that in the face of what Ó Cadhain and others considered to be the economic and social as well as the linguistic threats to the Gaeltachts.

Misneach’s best known public interventions took place in 1966 when members, supported by the Dublin Brigade of the IRA, disrupted meetings of the Language Freedom Movement in Jury’s Hotel and the Mansion House. The disruptors taunted the platform with Union Jacks and sang God Save the Queen in a not overly subtle inference as to the motivations of the organisers.

Part of the new militancy was to emphasise the need for a co-operative based autonomous political and economic basis to ensure that the Irish speaking regions were not completely destroyed by unemployment and emigration. That coincided with the revival of republican activism based on what later became the Éire Nua policy and attracted the support of other language activists including the late Desmond Fennell.

It is certainly true that Ó Cadhain was attracted by this aspect of a reinvigorated republican movement led by the IRA. However, while his initial sympathies following the 1969/1970 split would appear to have been with the Official side in that split, it is unlikely he would have followed them down the path of the ultra Stalinist antipathy to all aspects of Irish culture as epitomised by the Workers Party’s Irish Industrial Revolution and its influence within RTÉ and other media. The after-effects of which are even still evident.

Desmond Fennell encapsulated not only the contemporary reaction to the language movement in the Gaeltacht, but of the enduring attitudes among the elite when he wrote that:

A pluralist Ireland, that is to say an Ireland in which various communities shaped their lives as they saw fit, was anathema to the new liberals. What we called Gaeltacht self-government, they smeared as apartheid.

Little has altered other than that the bourgeois liberals have been joined by most of the left. It is invidious to claim the legacy of any dead person, but given that the legacy of Ó Cadhain has arguably been misappropriated it is not remiss to speculate that it is unlikely he would have found himself on the same side as the neo-liberals or of the statist left with their common refrain that Ireland is nothing more than a multi cultural melting pot provided for the interests of corporate capital or its ideological bed fellows on the left who espouse a nebulous internationalism.

The positive achievements of Ó Cadhain lie in his literary prose and his writings on the language, but also in the achievement of limited Gaeltacht autonomy through Údarás and the establishment of both Raidió na Gaeltachta and Teilfís na Gaeilige. His linking of the fate of the language as well as all other aspects of our culture to the social and economic well being of the people remain as valid now as 50 years ago.

|

| San Aerfort i mBleá Cliath |

Máirtín Ó Cadhain: Rí an Fhocail - The King of Words

No comments