David Pearce’s GB84 is a good example of this. Gareth Mulvenna’s fictional short stories are fascinating snapshots into times and places of the Troubles. The Stray Bullets podcast on Spotify, created by E. S. Haggan contains textured, vivid accounts of actual events from a number of perspectives and narratives. Resurrection Men, by Eoin McNamee, portrays 1970s Belfast in all its claustrophobia. I had high hopes for McNamee’s book about the security forces in NI, The Ultras – hopes which were dashed. I found the book hard-going. Individual depictions of certain events grabbed the attention, but the overall arc of the novel drifted. This was not the case with the book I am reviewing. I actually read it in two days – one of those books you take for the journey somewhere, and end up sitting up engrossed until late into the night.

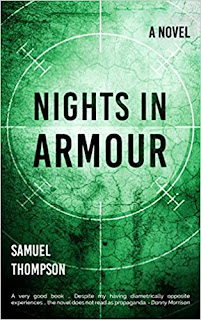

Samuel Thompson’s Nights in Armour is a good example of a novel that sits easily on a shelf with history books, and memoirs, covering the troubles. Thompson is an ex-RUC man, and his novel takes place in the early 1980s in Altnavellan; a fictional small town in Northern Ireland. Thompson’s skill as a writer created a vivid town that felt familiar.

I’ve decided to structure this review in themes – subjects that will interest readers of this blog, and students of the Troubles. That is not to say that the plot and the narrative are in any way lacking – they aren’t: but in a review of this size, I don’t want to give much of the story away, and think that one of the books strengths is the personal and often overlooked details it provides to an historic and much studied time in Irish history.

Life in Altnavellan RUC

The book opens with a vehicle check point (VCP), and an incident in which the RUC members get into a fire-fight with “terrorists”, resulting in casualties for the irregular forces (INLA). We are introduced to Sgt Brady, and constables Reid and Craig. The next part of the chapter describes a dream, in such a manner that the mind’s eye looks at the images and processes the additional information: The RUC in Derry in 1969 wore winter overcoats because the wool added a layer of protection against the stones raining down on them. Those images made sense now. This dream featuring the “ancient hatreds” of Ireland is ended by (RUC officer) Montgomery’s alarm clock going off. We find out two things about Montgomery: he likes a Bushmills in the morning, and he lives a mere four miles from where three INLA men were shot dead by the RUC. I found the use of a dream a meaningful device in setting the scene for this character’s psyche. It gave a sense of the weight of history and of personal experiences bearing down on this man. The somewhat pathetic nature of his protective clothing against the deluge of masonry raining down on him and his brother officers suggests a fragility and corresponding harmlessness.

Thompson uses sparse, effective details to give us an idea of what type of men, and RUC officers, the participants in the gunfight are. The hesitant Brady, the eager Reid. Their characters, and Montgomery’s, are developed throughout the book, Reid’s in particular taking some interesting twists and turns.

The aftermath of the shooting give us an insight into the RUC machinations following such an incident, and also of how concerns about “anti-Catholic” serving officers were dealt with. The section will allow detractors of the RUC ammunition to attack them for not taking it seriously enough, and supporters of the RUC with enough ammunition to say that not only did they take it seriously, they hampered their own officers. More neutral observers might see a bureaucracy with a culture that was trying to change, but was still an imperfect entity staffed with imperfect humans, drawn mostly from one side of a conflict wracked pocket of Europe.

We are introduced to Healy, a senior officer, keen to get the potentially problematic Reid transferred. Healy notes that Reid had caught the attention of An Phoblact, and raised the idea that this could compromise his safety. Reid is impatient, and has no time for the senior officer. And we find out he also has little respect for Montgomery who, is transpires, is not a uniformed officer like Reid, though he later finds himself in uniform.

Montgomery is regarded as “one of the old school” by younger officers, a member of an “old, almost forgotten force.” The book is peppered with insider knowledge of RUC life: parade time; the station plaque honouring the station’s dead; RUC officers drifting from their friendships outside the force; briefings about imminent but non-specific IRA attacks on the police and army, and the endemic tiredness and fear suffered by all. “If they want you, they’ll get you” was a common attitude at Altnavellen RUC station.

Republicans

After the introduction to Jim Reid, and the RUC, a sympathetic, well pitched and toned depiction is given of the brother of an IRA man and the republican estate that he lives in. Again, period detail is rich and engrossing, and evoked memories. The murals with “skeletal prisoners” - men on the blanket, the stray dogs, the rain. Eamon Lynch, who we are introduced to in this section, hates the police and the army, and is openly disdainful of them. The author, through Lynch, correctly notes that Scottish regiments were often more feared than English ones.

Whilst it is now obvious to me looking back, I had never realised that it was the army throwing paint over republican murals, as the author says. I had always assumed it was local, rather than military, vandals.

Non-political policing and life as normal

Whilst the backdrop to the novel is the conflict, the novel vividly describes aspects of police-work that are not for the fainthearted. Dealing with decomposing corpses, unruly livestock, and truculent farmers are described. The humanness of the characters is depicted through relatable relationship dynamics. “Normalisation” is seen through the book, in a non-political sense. Life really did go on. Restaurants opened in Belfast city centre. People lived and fell in love, and hit the drink, and argued with their wives. Class distinctions were alive and well, and snobbery lived alongside, and intersected, with sectarianism. And the difficulties of getting a drink on a Sunday was a burden experienced by all . . .

The Siege Mentality

The chapter “On the Beat” notes that the only Protestant estate Hilliside, is “north of the river.” A grand, Gothic cathedral is described, with military banners and flags festooned on the walls, bearing battle wounds from Waterloo. This reminded me of Eamon Collins observation, upon singing in a choir inside Protestant churches (so he could more effectively target RUC officers), that he was amazed at such military displays in Protestant places of worship. I realised upon reading Collins words that I had never noticed this. Afterwards, I noticed it every time I found myself in a Protestant church.

The constant threat RUC officers were under is illustrated by the hapless Montgomery, walking alongside Reid, and thus doubling the available targets. A special branch officer, Hoycroft, discusses the threat relayed to Reid – interestingly, Reid is given a different version of what Healy told him. Hoycroft also observes that republicans “don’t think like us” when considering revenge. Reid is told a uniform is their target, and that “any peeler would do.”

“It was him who started all this”

As the RUC patrol passes through Irish Street, we revisit Eamon Lynch and his friends. I have to admit I bristled at the depiction of directionless lives, cider consumption, and bitterness and frustration in a Catholic/Nationalist area. Having lived in one, arguably the most famous/infamous one in the whole of the North, the nihilistic youths depicted certainly did exist, but they seemed more numerous, to me anyway, on the Shankill, or on Sandy Row. But maybe I just noticed the industrious, mostly content, crafty but kind working men in pubs in and around the Falls. But we are given an RUC officer’s depiction of some lives in that area, and the discomfort I felt was partially tribalism, and partially recognising a degree of accuracy. The RUC officers, their vehicle attacked with bottles by Lynch and his friends, make arrests, fights break out, and, arguably, “minimum force” is ignored. Batons are drawn. Reid violently quashes aggression from one of the arrested men. And one of the RUC officers angrily thinks, about one of the arrested, “it was him who started all this.” That classic Irish tautology. The author is not unkind to Lynch and his friends. And he is not overly generous about the RUC actions, either.

Part Two to follow.

Samuel Thompson, 2019, Nights in Armour. Available @ Mercier Press. ISBN-10:178117699X

ISBN-13:978-1781176993

⏩ Brandon Sullivan is a middle aged, middle management, centre-left Belfast man. Would prefer people focused on the actual bad guys.

This looks one to read. The book obviously struck you Brandon given the amount of work you have put into reviewing it. Novel writing we hear a lot about former republican prisoners doing but not so much former RUC. And it sounds nothing like Morrison's West Belfast which was pretty poor. Although The Wrong Man by Morrison is well worth a read. I am not opposed to novelists anchoring their work in the conflict but I think Sam Millar broke the mould with his novels.

ReplyDeleteI liked The Wrong Man. Saw a theatre production of it once.

ReplyDeleteI haven't read Sam Millar's stuff - will have a look.

I've started The Slowworm's Song by Andrew Miller, which is good.