Even Alok Sharma – Boris Johnson loyalist, former Tory cabinet minister, now president of the COP 26 UN climate summit in Glasgow in November – says he recognises it: the planet is in the last-chance saloon. Indeed, the scientists on the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) warn, the clock – to borrow George Orwell’s opening to 1984 – has already struck thirteen. “Human activity,” reported The Guardian, “is changing the Earth’s climate in ways unprecedented in … hundreds of thousands of years”: some potentially disastrous consequences are “inevitable and ‘irreversible’”.

Only the worst effects can now be alleviated, and that only by decisive action drastically to reduce greenhouse gas emissions. Without a serious move to end reliance on fossil fuels, human society as we know it faces extinction. And, argues this book, Britain is a nation the modern existence of which has been shaped by oil. What hope is there for the future?

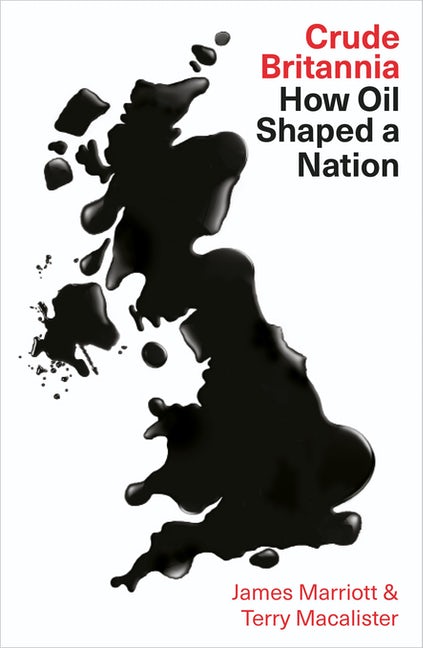

The publication of Crude Britannia: How Oil Shaped a Nation is timely indeed. That James Marriott and Terry Macalister had fun researching it resonates in their writing, but it must have been hard work too. It took them about three years longer than planned, when the instability that afflicted Britain in the years following the 2007-09 financial crash prompted their project. The effects of austerity; the near-miss 2014 Scottish independence referendum that raised the now immanent possibility that the 314-year-old union with England could end, and with it the fragile constitutional underpinnings of the United Kingdom; “Brexit”; growing fears of climate catastrophe … it all made the nation look unprecedentedly insecure.

Only the worst effects can now be alleviated, and that only by decisive action drastically to reduce greenhouse gas emissions. Without a serious move to end reliance on fossil fuels, human society as we know it faces extinction. And, argues this book, Britain is a nation the modern existence of which has been shaped by oil. What hope is there for the future?

The publication of Crude Britannia: How Oil Shaped a Nation is timely indeed. That James Marriott and Terry Macalister had fun researching it resonates in their writing, but it must have been hard work too. It took them about three years longer than planned, when the instability that afflicted Britain in the years following the 2007-09 financial crash prompted their project. The effects of austerity; the near-miss 2014 Scottish independence referendum that raised the now immanent possibility that the 314-year-old union with England could end, and with it the fragile constitutional underpinnings of the United Kingdom; “Brexit”; growing fears of climate catastrophe … it all made the nation look unprecedentedly insecure.

|

| A protest against new oil field development in Scotland. Photo by Craig Maclean |

Experts in their different ways in the central socio-economic role of oil in the modern world, Marriott and Macalister decided to investigate the part it had played in holding the Britain of recent decades together – and is now playing in tearing it apart. They would travel the country, researching its post-World-War-II relationship with the industry. Then, as they were reaching their journey’s end, the Covid-19 pandemic dealt the final blow to what to them – children, as they introduce themselves, of the years in which oil replaced coal in the engine-room of British prosperity and sustained the underlying certainties of the country’s political economy and social life – had seemed an “era of optimism”. They “had spent [their] lives writing on the oil and gas industry and its impacts around the world”, and now wanted to understand “what was its role … in Britain’s turbulence?”

Marriott and Macalister make an ideal pair to ask the question, and they have devised an entertaining, instructive and original way of starting serious debate about answering it. The delay in their publication plans, moreover, means that their book has arrived at an opportune moment. The protest movement is gathering momentum, notably in London against the Science Museum’s acceptance of Shell’s “greenwashing” sponsorship for its “Future of the Planet” exhibition and, in Scotland, against further North Sea oil exploitation, in the first place of the Cambo field, west of Shetland. And planning is well underway for major demonstrations at the COP 26 summit that the smooth and well-travelled (although never-quarantined) Sharma is scheduled to chair in Glasgow in November – described by Kevin McKenna in The Herald (Glasgow) recently as an exercise in entrusting “our climate recovery … to the sector chiefly responsible for creating it … the planet’s chief pollutant: global capitalism.”

Macalister, now Senior Research Fellow at Wolfson College, Cambridge and a freelance journalist, was for some years Energy Editor at The Guardian – a position in which he clearly formed working relationships with key figures in the oil industry, access to whom adds important insights to Crude Britannia. Interviewees include senior politicians such as Michael Heseltine and “Green Deal” Corbynite, Rebecca Long-Bailey; and chief executives such as Royal Dutch Shell’s Bernardus (or “Ben”) van Beurden, and John, Baron Browne of Madingley. Browne was British Petroleum’s chief executive from 1995 until 2007, and his shape-shiftingly image-conscious, but never less than ruthless, career punctuates the story at key moments. His 41 years with BP ended following the revelation that he had lied about his personal life in a sworn court deposition. Now a cross-bench peer, he emerges as one of the key business figures in the “new Labour” years. His ultimately unsuccessful attempts to rebrand BP as “Beyond Petroleum” with a sun-god logo, dovetailed well with premier Tony Blair’s short-lived “third way”, capitalism-with-a-human-face ideology.

Marriott’s complementary qualifications include having co-authored in 2012 (with Mika Minio-Paluello) an innovative travel book, The Oil Road: Journeys from the Caspian Sea to the City of London. It follows an itinerary from the oilfields of the Caucasus to the controlling web of the metropolitan financial and corporate institutions of London. It has more exotic locations and anthropologically intriguing human-interest tales than Crude Britannia, for which it provided a methodological template. Marriott, moreover, is a campaigner who works with Platform, a group that brings together artistic, educational and research initiatives with activism focused on social and ecological justice. The group last year contributed to the “just transition” campaign, by surveying North Sea workers – men and women seldom consulted by political campaigners, far less policymakers – and showing that more than 80% of them would consider leaving their oil and gas jobs if a credible alternative were on offer. (A not dissimilar conclusion came from a more recent Canadian survey, when a parallel question was asked of oil workers there.)

In addition to their abiding interest in energy and the climate crisis, the journalist-scholar and the artist-activist share a love of contemporary music. At an online launch event in May, Macalister said the project had focused on “the key places where [the industry and its offshoots] had solidly placed its footprint”; in research centres, refineries, plants and pipelines.They were bent on “soaking up the atmosphere in the Thames Estuary, South Wales, Merseyside and North East Scotland”, and talking to people on the ground, as well as in the power-centres of London and The Hague. But they have enhanced the account of their zig-zagging, back-and-forth journey around the UK with illuminating snatches from lyrics – from The Beatles’ Baby, You Can Drive My Car (1965), via Orchestral Manoeuvres in the Dark’s Stanlow (1980) (“the only British pop song written about an oil installation”) to Slovo vocalist Barbarella’s Deliver Us (2020). You can listen to the playlist of 16 tracks referred to while you read. It all makes for a stimulating firework display of a book, as chronological narrative criss-crosses, sometimes repetitively, with thematic and topographical contexts.

Oil history

Within three principal sections, spanning respectively 1940-1979, 1979-2008 and 2008-2020, Crude Britannia skilfully brings together stories told by people from a wide variety of backgrounds and occupations: secretive (but to Marriott and Macalister surprisingly open) oil traders; technicians; refinery workers; trade unionists; climate-change activists; community leaders; film-makers and musicians. Their stories form the building blocks of the book, adding something new to a literature that, in the last few years, has begun at last to challenge the conventional “there [was] no alternative”, quasi-Thatcherite version of contemporary British history – which, intellectually and politically, dominated the early years of this century.

From that point of view, Crude Britannia deserves to be taken seriously as a contribution to historical scholarship. But Marriott and Macalister, concerned to address a wide audience, banish their academic credentials to the back: there are 710 endnotes which, with the bibliography, take up about one fifth of the book’s 430 pages, and often contain information that could have been in the main text, had the authors not been bent on ensuring that their work is not mistaken for, as Macalister put it, “an academic tome”.

The unifying idea behind Crude Britannia is well expressed by Helen Thompson, a professor of political economy at Cambridge University, whom the authors quote, saying that she herself had planned to write about the fallout of the financial crisis, with one focus on energy. But when she tried to bring “oil into things [she already] knew about”, she concluded that it was not a question of “introducing oil into the other stories [because] oil is the story” [emphasis added]. To her, the puzzle is that this is rarely discussed. Oil, she thinks, is “so big” that it permeates everything from daily living to foreign policy decisions to climate change. It is something that, at many different levels of discourse, “people don’t really want to think about”.

Marriott and Macalister make an ideal pair to ask the question, and they have devised an entertaining, instructive and original way of starting serious debate about answering it. The delay in their publication plans, moreover, means that their book has arrived at an opportune moment. The protest movement is gathering momentum, notably in London against the Science Museum’s acceptance of Shell’s “greenwashing” sponsorship for its “Future of the Planet” exhibition and, in Scotland, against further North Sea oil exploitation, in the first place of the Cambo field, west of Shetland. And planning is well underway for major demonstrations at the COP 26 summit that the smooth and well-travelled (although never-quarantined) Sharma is scheduled to chair in Glasgow in November – described by Kevin McKenna in The Herald (Glasgow) recently as an exercise in entrusting “our climate recovery … to the sector chiefly responsible for creating it … the planet’s chief pollutant: global capitalism.”

Macalister, now Senior Research Fellow at Wolfson College, Cambridge and a freelance journalist, was for some years Energy Editor at The Guardian – a position in which he clearly formed working relationships with key figures in the oil industry, access to whom adds important insights to Crude Britannia. Interviewees include senior politicians such as Michael Heseltine and “Green Deal” Corbynite, Rebecca Long-Bailey; and chief executives such as Royal Dutch Shell’s Bernardus (or “Ben”) van Beurden, and John, Baron Browne of Madingley. Browne was British Petroleum’s chief executive from 1995 until 2007, and his shape-shiftingly image-conscious, but never less than ruthless, career punctuates the story at key moments. His 41 years with BP ended following the revelation that he had lied about his personal life in a sworn court deposition. Now a cross-bench peer, he emerges as one of the key business figures in the “new Labour” years. His ultimately unsuccessful attempts to rebrand BP as “Beyond Petroleum” with a sun-god logo, dovetailed well with premier Tony Blair’s short-lived “third way”, capitalism-with-a-human-face ideology.

Marriott’s complementary qualifications include having co-authored in 2012 (with Mika Minio-Paluello) an innovative travel book, The Oil Road: Journeys from the Caspian Sea to the City of London. It follows an itinerary from the oilfields of the Caucasus to the controlling web of the metropolitan financial and corporate institutions of London. It has more exotic locations and anthropologically intriguing human-interest tales than Crude Britannia, for which it provided a methodological template. Marriott, moreover, is a campaigner who works with Platform, a group that brings together artistic, educational and research initiatives with activism focused on social and ecological justice. The group last year contributed to the “just transition” campaign, by surveying North Sea workers – men and women seldom consulted by political campaigners, far less policymakers – and showing that more than 80% of them would consider leaving their oil and gas jobs if a credible alternative were on offer. (A not dissimilar conclusion came from a more recent Canadian survey, when a parallel question was asked of oil workers there.)

In addition to their abiding interest in energy and the climate crisis, the journalist-scholar and the artist-activist share a love of contemporary music. At an online launch event in May, Macalister said the project had focused on “the key places where [the industry and its offshoots] had solidly placed its footprint”; in research centres, refineries, plants and pipelines.They were bent on “soaking up the atmosphere in the Thames Estuary, South Wales, Merseyside and North East Scotland”, and talking to people on the ground, as well as in the power-centres of London and The Hague. But they have enhanced the account of their zig-zagging, back-and-forth journey around the UK with illuminating snatches from lyrics – from The Beatles’ Baby, You Can Drive My Car (1965), via Orchestral Manoeuvres in the Dark’s Stanlow (1980) (“the only British pop song written about an oil installation”) to Slovo vocalist Barbarella’s Deliver Us (2020). You can listen to the playlist of 16 tracks referred to while you read. It all makes for a stimulating firework display of a book, as chronological narrative criss-crosses, sometimes repetitively, with thematic and topographical contexts.

Oil history

Within three principal sections, spanning respectively 1940-1979, 1979-2008 and 2008-2020, Crude Britannia skilfully brings together stories told by people from a wide variety of backgrounds and occupations: secretive (but to Marriott and Macalister surprisingly open) oil traders; technicians; refinery workers; trade unionists; climate-change activists; community leaders; film-makers and musicians. Their stories form the building blocks of the book, adding something new to a literature that, in the last few years, has begun at last to challenge the conventional “there [was] no alternative”, quasi-Thatcherite version of contemporary British history – which, intellectually and politically, dominated the early years of this century.

From that point of view, Crude Britannia deserves to be taken seriously as a contribution to historical scholarship. But Marriott and Macalister, concerned to address a wide audience, banish their academic credentials to the back: there are 710 endnotes which, with the bibliography, take up about one fifth of the book’s 430 pages, and often contain information that could have been in the main text, had the authors not been bent on ensuring that their work is not mistaken for, as Macalister put it, “an academic tome”.

The unifying idea behind Crude Britannia is well expressed by Helen Thompson, a professor of political economy at Cambridge University, whom the authors quote, saying that she herself had planned to write about the fallout of the financial crisis, with one focus on energy. But when she tried to bring “oil into things [she already] knew about”, she concluded that it was not a question of “introducing oil into the other stories [because] oil is the story” [emphasis added]. To her, the puzzle is that this is rarely discussed. Oil, she thinks, is “so big” that it permeates everything from daily living to foreign policy decisions to climate change. It is something that, at many different levels of discourse, “people don’t really want to think about”.

|

| From Pluto Press in paperback |

But of course more and more people, especially young people, do want it thought – and talked – about. And they want to see action that challenges the economic and political elites, who are desperate to keep discussions about the future of oil within careful limits. Crude Britannia provides a narrative the authors describe as the “hidden” or “submarine” history of how, as the book’s subtitle has it, oil has “shaped a nation” – the post-imperial UK. It encourages us to understand better that overcoming the economic and political power of the oil industry can not be achieved without radically transforming that nation, and, indeed, the world of globalised capital of which it is a much-diminished, but still significant, part.

Crude Britannia begins with the role of oil in World War II, during which Shell had been “effectively split into an Allied corporation and an Axis corporation”. The latter, Rhenania-Ossag, flew the Swastika at its HQ in The Hague and helped fuel the Nazi state. In the Battle of Britain, “a dogfight over the Channel between a Messerschmitt and a Spitfire could have seen both planes fuelled by Shell”.

We learn that, in 1941, Macalister’s father was in the North African desert with the RAF, when lack of diesel thwarted the Axis powers’ drive for easy access to Iranian oil fields, and aviation fuel kept British fighters in the air. Marriott’s family lived in rural Yorkshire, in a cottage heated with coal and connected to cities by steam train. But, the authors imply, it was being born at this “moment of global oil wars”, when “Britain took a pivotal switch away from coal” that led their lives on an ultimately convergent course. They were “travel[ing] in cars before [they] were born … [and then] suckl[ing] on rubber teats and dummies that were the outputs of petrochemical plants.” Oil was fundamental to their generation’s upbringing. “Plastic toothpaste tubes, holidays abroad, nylon clothes, food packaging, detergents, collecting oil company stickers and garage giveaways” were all made possible by “the abundance of cheap oil that fuelled the optimism of the era”.

From that engagingly personal beginning, Crude Britannia takes readers through the UK’s post-war years of industrial recovery. It’s a story of increasingly all-pervasive petrochemicals; of the oil imperialism that made Britain a pariah-power in Iran, Nigeria and elsewhere; of the growth of civilian air travel; of the discovery of recoverable energy resources in the North Sea; and of the Middle East oil crises of the late 1960s and early 1970s. Then come the Thatcher governments, with their determination to destroy trade-union power and use the Americanised, offshore North Sea oil and gas industry as the model for the privatisation policy that would give the UK a new “shape”; or rather would reshape the social-democratic nation and recreate it as a beacon for global, “neoliberal” capital.

As the UK shifted from being a coal-fired to an oil-fired nation, so the situation in which the major corporations – and BP remained majority-state-owned into the 1980s – had to at least adapt themselves to government-determined, welfare-state, social priorities, shifted decisively to one in which governments, whatever their declared politics, became the tool of the corporations.

Crude Britannia’s second section takes us into a period when the “crucible of British political direction lay in the struggle between its financial sector and its industrial areas”: the “oil companies played a pivotal role … not only in the City’s battle over the development of the North Sea but in the manufacturing heartlands such as South Wales”. These were the years of the “pushback against union power, and [against] Labour’s drive to nationalise assets”; though just how serious that drive was, especially from the mid 1970s on, can be questioned.

Not the least of Crude Britannia’s virtues is that it debunks the myths that still surround Tony Benn, and had their part to play in the delusions of Corbynism – based in the great populist’s own accounts of how, when he was Energy Secretary, he stood up to the oil companies and sent them packing in the name of “democracy”. As Marriott and Macalister point out, when the BP chairman at that time, David Steel, died in 2004, one obituary headline referred to him as the executive “who triumphed over Tony Benn”; but when Benn died ten years later, his “departure was accompanied by acres of newsprint and yet there was little mention of the … struggle which had taken place in [the BP headquarters at] Britannic Towers”.

|

| The protest against oil field development at Cambo, west of Shetland. Photo by Craig Maclean |

Any effective action against the social effects of the financialisation of British capital – and there are several stories illustrative of this in Crude Britannia – came not from the “Labour movement” leadership, but from rank-and-file trade-union and community activists; and, important and still inspiring though its successes were, they were inevitably limited.

At the launch event, Macalister described Crude Britannia as “a social history [and] a travelogue”, that is “also a climate action handbook” to help campaigners in their struggle – against the vested interests of governments and the now retreating and less confident, but still powerful and profit-driven, corporations – for a post-fossil-fuel world. In the book’s third section, covering the years since 2008, this last element comes to the fore.

The concluding chapters are presented as dated diary entries – at first chronological, then organised around particular themes – that take readers through a number of key events with implications for the future of the “oil-shaped” nation and some important moments in the authors’ research journey:

- 18 December 2008: news of the Lehmann Brothers collapse;

- 21 April 2010: the explosion of the BP Deepwater Horizon oil-rig in the Gulf of Mexico (“reviving memories of the Piper Alpha disaster 22 years previously”);

- 28 June 2010, when the eventually successful campaign to “liberate” the Tate Gallery from BP sponsorship began;

- 21 May 2013: a Shell AGM at which organisations like Greenpeace, Platform, Share Action, and Resisting Environmental Destruction on Indigenous Lands challenged the company’s destructive activities in the Arctic;

- December 2015: the Paris Climate Summit;

- 14 April 2016: a BP AGM Marriott and Macalister take as a moment, with CEO Bob Dudley on the back-foot, from which to survey some of the often-courageous, and by then increasingly effective, campaigns to influence public opinion about the disastrous environmental impacts of the industry;

- 11 December 2017: the leak in Aberdeenshire from the INEOS pipeline that cut off much North Sea crude for weeks.

This last event led Marriott and Macalister to BP Integrated Supply and Training at Canary Wharf, to examine the world of oil trading, which – increasingly the determining force in the industry – depends not on production, but on exploiting the financial opportunities offered by the share-price volatility that follows such events.

The authors’ return to north east Scotland brings us back to North Sea oil. Crude Britannia is primarily about Shell and BP and the impact of their worldwide history on Britain and on the climate crisis. North Sea oil, and the way it fuelled the rise of the Scottish National Party in the 1970s, features – but less centrally than it would have done had the prospect of the UK breaking up been a more central theme. Had that been the case, Marriott and Macalister might have consulted the extensive Lives in the Oil Industry oral history archive (LOI), a resource they appear to have overlooked. (It is accessible at Aberdeen University and the British Library, and, when delays caused by the pandemic have been overcome, will be on line. More detail in an article in Northern Scotland here.)

Engagement with these interviews would have changed neither their central narrative nor their campaigning purpose, but it might have led to the 1988 Occidental Oil Piper Alpha disaster, and the offshore workers’ safety-regime-focused, trade union actions in its aftermath, receiving greater attention. Crude Britannia has a short account of the authors’ visit to Sue Jane Taylor’s intensely moving – if somewhat monumental – memorial, all too easily missed by visitors to Aberdeen in the city’s suburban Hazlehead Park; and one of the most striking items on the book’s playlist is the classical composer James Macmillan’s lament for the victims, Tuireadh (also the title of Chapter 7). But somehow, despite a number of references, the full historical impact of Piper Alpha is missing.

|

The Piper Alpha memorial in Hazlehead Park, Aberdeen. Photo by Lizzie / Creative Commons |

In the LOI archive you can, for example, listen to Tim Halford, PR man for Occidental owner Armand Hammer, recounting how his boss, sensing the threatening tremors from below on the platform’s surface, laughed them off as the welcome rumbling of “those dollars flowing underneath”. You can live for an hour or two with the late Bob Ballantyne, giving a survivor’s account of his narrow escape, his rescue from the freezing North Sea, the pain of the loss of his closest mates, and the experience of giving evidence to the subsequent Cullen Enquiry.

Such witness statements – exemplifying not only the industry’s subordination of life to profit, but also the complaisant priorities of the political regime that legitimised and encouraged its activities – should help to put the Piper Alpha story at the centre of any critical history of UK North Sea oil. History, as Marriott and Macalister assuredly recognise, matters, particular the history that lies just beyond the memory reach of most of the young campaigners they surely hope will read their book.

From Ballantyne – and from other offshore workers interviewed for the LOI archive – there is much to learn, too, from the post-Piper Alpha campaign for a human-life-centred North Sea safety regime; and from the experience of the Offshore Industry Liaison Committee trade-union (which gets only one brief reference in Crude Britannia) and its fight for this goal – often against the “official” unions’ reluctance to commit unequivocally to it.

An important source for the continued relevance of these stories is the account by another LOI participant, former offshore worker and now Extinction Rebellion activist, Neil Rothnie, of his more recent work attempting to draw the attention of journalists, fellow trade unionists and climate activists to the lessons of the 2012 near-miss catastrophe on the Elgin platform, when there was a major gas leak, not far from where Piper Alpha had exploded a quarter of a century earlier. The Elgin disaster-that-only-just-didn’t-happen, Rothnie has said recently, was, for him – because of its even more catastrophic potential, and the way it demonstrates the potentially fatal limits of the safety regime changes made since 1988 – more historic even than the Piper Alpha tragedy itself. But that is a story that, unless Rothnie’s writing about it receives wider public exposure, is unlikely to enter historical memory at all.

What we do get from Marriott’s and Macalister’s most recent visits to north east Scotland (in 2018 and 2019) are interviews with Jake Molloy, himself a veteran of the OILC experience, now a Rail, Maritime and Transport (RMT) union official, and with North Sea oil’s “official” historian, Aberdeen University professor Alex Kemp.

Molloy belongs to a generation of trade unionists who cut their militant teeth in the years of the “post-war boom” during which unions were recognised as, in Winston Churchill’s phrase, an “estate of the realm” – a period that ended decisively with Thatcher’s mobilisation of the full force of the state to defeat her “enemy within”, the National Union of Mineworkers, in 1984-85. Faced with the very different situation today, he talks not only about the impossibility of serious negotiations with the oil companies, but also about his fears that this dismissive culture is being replicated in the renewables industry.

Kemp is described as “a tiny man with a serious demeanour,” hidden “like an Elfin King” in an office made “almost completely inaccessible due to a mountain of research papers”. He offers the complacent opinion – a warning perhaps about the implications of much “official” thinking – that North Sea oil will last at least till 2045, even if increasingly without the direct involvement in production of the major international companies. The authors withhold comment, contenting themselves with securing professorial confirmation for the view that “oil played a major role in helping the Thatcher government defeat the miners”.

Looking forward: the meaning of hope

The final chapters of the book – “Nexus of Change”, “Heading for Extinction” and an epilogue, “The Commonwealth of Wind” – are, as these titles suggest, where the oil industry’s past is brought most directly into confrontation with the struggle over its future. Elite business and political views continue to be reported, but with increasing scepticism. And it is ideas such as those informing the “electrifying speech” made in Parliament Square on 23 April 2019, when Extinction Rebellion mounted its attempt to blockade London, by Elsie Luna – “the ten-year old … who went on to found XR Kids” – that provide momentum to Crude Britannia’s concluding pages.

Luna is given Crude Britannia’s parting comments, expressing her frustration “with oil companies, governments and even Extinction Rebellion”. Insofar as “civil society [is] changing Britain and the oil companies”, she thinks, it is doing so far too slowly; and “XR is wrong to prioritise climate over justice”, because “neither is more important than the other”. The companies “are continuing to exploit land and indigenous peoples just to make themselves rich … [their] talk of decarbonisation is just greenwash” and “current [governmental] systems” are incapable of taking the “decisions needed”. But she is “definitely not” giving up. The work that’s needed, which she says she intends to participate in, must aim “to change the politics” and that “starts … with local communities.” Luna’s youthful resilience sets up Marriott and Macalister’s final aphorism. “In the ruins of an oil world,” they conclude “the new is being built.”

This hopeful phrase – and the way in which it is attached to implicit faith in the capacity for effective struggle of a new generation – arguably encapsulates the essence, and the limits, of the forward thinking that informs the book. It was latched on to by Green MP, Caroline Lucas, whose stress, when she chaired the Crude Britannia launch, was on the opportunities for change offered by the perceived seriousness of the crisis; and on the, in reality relatively small-scale, steps being taken in some places to address it.

Participants, along with the chair and the authors, were Gail Bradbrook, coalminer’s daughter, biophysicist, campaigner for disabled people’s web access and cofounder of Extinction Rebellion; Suzanne Dhaliwal, cofounder of the Tar Sands Network that has challenged Shell and BP on their destructive activities in Canada, and a lecturer in environmental justice and decolonisation strategies; Dave Randall, the guitarist who founded the band Slovo, also a writer and political activist; and the RMT’s Jake Molloy.

As a group – a radical politician, journalists, campaigners, a musician and a trade unionist – they represent key elements in the coalition of activists that the book aspires to inform, as the political pressure grows for what, as Luna’s comments tentatively suggest, has to be systemic change, going far beyond simply gaining governmental and industry commitments to environmental targets.

Such witness statements – exemplifying not only the industry’s subordination of life to profit, but also the complaisant priorities of the political regime that legitimised and encouraged its activities – should help to put the Piper Alpha story at the centre of any critical history of UK North Sea oil. History, as Marriott and Macalister assuredly recognise, matters, particular the history that lies just beyond the memory reach of most of the young campaigners they surely hope will read their book.

From Ballantyne – and from other offshore workers interviewed for the LOI archive – there is much to learn, too, from the post-Piper Alpha campaign for a human-life-centred North Sea safety regime; and from the experience of the Offshore Industry Liaison Committee trade-union (which gets only one brief reference in Crude Britannia) and its fight for this goal – often against the “official” unions’ reluctance to commit unequivocally to it.

An important source for the continued relevance of these stories is the account by another LOI participant, former offshore worker and now Extinction Rebellion activist, Neil Rothnie, of his more recent work attempting to draw the attention of journalists, fellow trade unionists and climate activists to the lessons of the 2012 near-miss catastrophe on the Elgin platform, when there was a major gas leak, not far from where Piper Alpha had exploded a quarter of a century earlier. The Elgin disaster-that-only-just-didn’t-happen, Rothnie has said recently, was, for him – because of its even more catastrophic potential, and the way it demonstrates the potentially fatal limits of the safety regime changes made since 1988 – more historic even than the Piper Alpha tragedy itself. But that is a story that, unless Rothnie’s writing about it receives wider public exposure, is unlikely to enter historical memory at all.

What we do get from Marriott’s and Macalister’s most recent visits to north east Scotland (in 2018 and 2019) are interviews with Jake Molloy, himself a veteran of the OILC experience, now a Rail, Maritime and Transport (RMT) union official, and with North Sea oil’s “official” historian, Aberdeen University professor Alex Kemp.

Molloy belongs to a generation of trade unionists who cut their militant teeth in the years of the “post-war boom” during which unions were recognised as, in Winston Churchill’s phrase, an “estate of the realm” – a period that ended decisively with Thatcher’s mobilisation of the full force of the state to defeat her “enemy within”, the National Union of Mineworkers, in 1984-85. Faced with the very different situation today, he talks not only about the impossibility of serious negotiations with the oil companies, but also about his fears that this dismissive culture is being replicated in the renewables industry.

Kemp is described as “a tiny man with a serious demeanour,” hidden “like an Elfin King” in an office made “almost completely inaccessible due to a mountain of research papers”. He offers the complacent opinion – a warning perhaps about the implications of much “official” thinking – that North Sea oil will last at least till 2045, even if increasingly without the direct involvement in production of the major international companies. The authors withhold comment, contenting themselves with securing professorial confirmation for the view that “oil played a major role in helping the Thatcher government defeat the miners”.

Looking forward: the meaning of hope

The final chapters of the book – “Nexus of Change”, “Heading for Extinction” and an epilogue, “The Commonwealth of Wind” – are, as these titles suggest, where the oil industry’s past is brought most directly into confrontation with the struggle over its future. Elite business and political views continue to be reported, but with increasing scepticism. And it is ideas such as those informing the “electrifying speech” made in Parliament Square on 23 April 2019, when Extinction Rebellion mounted its attempt to blockade London, by Elsie Luna – “the ten-year old … who went on to found XR Kids” – that provide momentum to Crude Britannia’s concluding pages.

Luna is given Crude Britannia’s parting comments, expressing her frustration “with oil companies, governments and even Extinction Rebellion”. Insofar as “civil society [is] changing Britain and the oil companies”, she thinks, it is doing so far too slowly; and “XR is wrong to prioritise climate over justice”, because “neither is more important than the other”. The companies “are continuing to exploit land and indigenous peoples just to make themselves rich … [their] talk of decarbonisation is just greenwash” and “current [governmental] systems” are incapable of taking the “decisions needed”. But she is “definitely not” giving up. The work that’s needed, which she says she intends to participate in, must aim “to change the politics” and that “starts … with local communities.” Luna’s youthful resilience sets up Marriott and Macalister’s final aphorism. “In the ruins of an oil world,” they conclude “the new is being built.”

This hopeful phrase – and the way in which it is attached to implicit faith in the capacity for effective struggle of a new generation – arguably encapsulates the essence, and the limits, of the forward thinking that informs the book. It was latched on to by Green MP, Caroline Lucas, whose stress, when she chaired the Crude Britannia launch, was on the opportunities for change offered by the perceived seriousness of the crisis; and on the, in reality relatively small-scale, steps being taken in some places to address it.

Participants, along with the chair and the authors, were Gail Bradbrook, coalminer’s daughter, biophysicist, campaigner for disabled people’s web access and cofounder of Extinction Rebellion; Suzanne Dhaliwal, cofounder of the Tar Sands Network that has challenged Shell and BP on their destructive activities in Canada, and a lecturer in environmental justice and decolonisation strategies; Dave Randall, the guitarist who founded the band Slovo, also a writer and political activist; and the RMT’s Jake Molloy.

As a group – a radical politician, journalists, campaigners, a musician and a trade unionist – they represent key elements in the coalition of activists that the book aspires to inform, as the political pressure grows for what, as Luna’s comments tentatively suggest, has to be systemic change, going far beyond simply gaining governmental and industry commitments to environmental targets.

|

| Slovo. Photo from the band’s web site |

You can not, as the youthful campaigner told Marriott and Macalister, “prioritise climate over justice” … to which Dhaliwal, the contributor at the launch who came closest to tempering her enthusiasm with creative critique, added that the environmental movement has to examine itself before it can seriously confront the oil companies. She appealed for an approach that challenges “the white supremacy” within the movement, and recovers the history of those who historically have been on the receiving end of the colonial system of which the oil industry has been a key part.

UK campaigns, she clearly feels, are too parochial, alienating many people from such backgrounds and are insufficiently attentive not only to this history but to some of the most powerful social movements today, such as that of the Indian farmers against the new laws they think will ruin their livelihoods. To this listener at least, Dhaliwal’s contribution came over as an urgent plea for critical thinking, that might lead some environmental campaigners beyond Bradbrook’s cheerful call to “keep going out on the streets” and doing what they enjoy “because we’re in this for the long haul”.

Molloy of the RMT spoke frankly to the launch about his dilemmas as a concerned trade unionist confronting what is now a systemic crisis of human society itself, very different from the sort of cyclical socio-economic crises in which unions were for long able to secure important gains for their members. Dave Randall called for more utopian and visionary thinking to offset the dystopian jeremiads the climate crisis has generated – and which are likely to be redoubled when the practical outputs from whatever agreements are reached by the capitalist powers in Glasgow in November begin to be seriously analysed.

Two important appeals can perhaps be heard in, or at least derived from, these contributions. The first concerns the recognition that class agency remains critical if radical transition – “just”, not only in employment terms, but in transition to a humanity-centred social metabolism – is to be accomplished. But in the so-called “advanced world” of the 21st century, it has to be recognised, class agency can no longer be equated simply with the struggles of the national, industrial working classes that many of us, in the second half of the twentieth century (and others long before then) thought – if only they were led by revolutionaries – held the future in their grasp.

The category that Karl Marx defined as the “structural antagonist” of capital, and therefore the only force that can bring about radical societal change to a “truly human future” was not the industrial working class he began to see emerging in the Europe of his own time as such, but “labour”. And that category has today to be fundamentally rethought as embracing much more diverse, and rapidly changing, forms of human activity than simply factory-work.

Prioritising the urgency of the climate crisis is no substitute for confronting such issues, since – whatever may be the impact of more immediate actions to delay the threat of planetary extinction – it is only by moving towards radical transition beyond the hegemony of capital, that humanity can secure its own, and the planet’s, long-term future.

The second implicit appeal that, to my ear, was just audible at the Crude Britannia launch was for activism to be informed with new thinking, by renewed attention to theory that interacts with, and guides, action. However much it is sustained by the unprejudiced enthusiasm of youth, activism which does not strive to generate and renew its own theoretical guidance, can – in the face of the ruthlessly destructive force of capital – only end in disillusion and defeat.

For this reason, it is important to pursue Randall’s comment on utopianism. Discouraging visionary and utopian thinking has always been a key weapon in the armoury of capital, whose ideologues promote a sense of impossibility and hopelessness. The most that women and men who understand the systemic nature of the injustices of existing society can be allowed by those ideologues to hope, and to fight, for, is piecemeal reform – what the Fabians Sidney and Beatrice Webb called “the inevitability of gradualness”.

Such limited aspiration has resulted in the hegemony of capital being prolonged far beyond its systemic compatibility with human need – to the point indeed at which the threat of extinction has become all too real. To have visions of a better future, and for those who can to sing about the hope they sustain, is, indeed, an important element in the response needed. But utopianism – which Marx and his comrade Friedrich Engels in the 1840s critiqued – and went beyond, in the forms in which it existed then – but did not reject, has to become part of more general theoretical renewal.

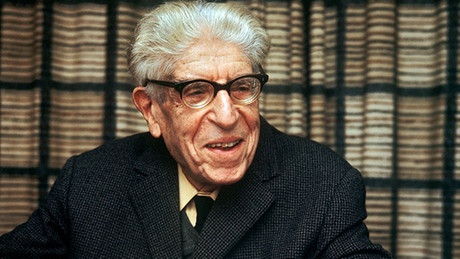

In East Germany in the 1950s, the philosopher Ernst Bloch – a long-standing student of utopian thinking, by then increasingly in conflict with the authoritarian Stalinist regime and its anti-humanist perversions of Marxism (he was soon effectively forced to leave his university chair, and the country) – called his most important book The Principle of Hope. Bloch’s work has recently found a new following amongst philosophy students, notably in Poland, but, in part no doubt because of its formidable length and eclectic form, it is seldom cited by theoretically-minded political campaigners in the West.

|

| Ernst Bloch. Photo from Notes towards an International Libertarian Eco-Socialism |

For the protest movements of today, to which Crude Britannia offers important encouragement to become something more than a loosely formulated urge to find a bright side amidst the encroaching gloom, Bloch offers a way of thinking about the relationship between past, present and future. This could create an intergenerational discourse between mid- to late-20th-century activists, licking their Marxist wounds in the aftermath of the now-decades-long, apparent triumph of “neoliberalism”, and the fresh forces drawn into struggle by today’s infinitely more profound crisis, within which lurks the threat of extinction.

Hope is an essential condition for such discourse, for it to be meaningful, and for it to have a positive outcome for humanity. But – in the face of the Himalayan nature of the challenge to end the long hegemony of capital, to prevent planetary catastrophe, and to find ways in which humanity can live in harmony with itself and with the natural world (and of course not only in the “oil-shaped” United Kingdom) – it must be hope based on serious intellectual and theoretical foundations. It is an achievement of Crude Britannia that it demonstrates that, even in the midst of the pressures of practical struggle against the threat of extinction, historical understanding matters. More important still, the book has the potential to begin a discussion about how the hope revived by a new generation of protestors could create the conditions for the rediscovery and renewal of those foundations.

There is much work to be done. / 23 August 2021

Download this review as a PDF here

■ Buy Crude Britannia here

■ Watch the Crude Britannia book launch

■ Just transition on the North Sea: let’s talk about public ownership – People & Nature, December 2020

⏭ Keep up with People And Nature. Follow People & Nature on twitter or instagram or telegram or whatsapp. Or email peoplenature@yahoo.com, and you will be sent updates.

No comments