Many commentators propose to raise this threshold in a manner that will block or indefinitely delay Irish reunification. I examine three such proposals, which together encompass the vast majority of attempts to “fix” the majority consent formula.[1]

Brendan O’Leary recently explored plausible demographic and political futures that point out the many problems with proposals to alter the GFA’s formula for constitutional change (O’Leary, 2021). Here, I use survey data over the past 23 years to show that the lived constitutional experiences of northern nationalists and republicans also point to the exceptionally problematic nature of the proposals.

The Proposals

The three proposals to change the Agreement’s simple majority formula have a number of major elements in common. First, they are contemptuously dismissive of the 50 percent + 1 rule, referring to it variously as old, ugly, undesirable, sectarian, crude and tribal (Burke, 2017). Second, their suggested replacement formulas increase unionist control over the constitutional status of the north by inserting a form of unionist veto over Irish unity. Third, the proposals fail to grant nationalists a reciprocal veto over maintaining the union. And fourth, they cavalierly reverse the democratic ratification of the Agreement in the referendums in May 1998. Since the GFA was endorsed by voters north and south, any fundamental change to its terms must also be popularly approved. All the proposals fail to recognize this basic democratic imperative. They would amend a very cornerstone of the GFA — its constitutional provisions — over the heads of voters, thereby estranging the people from the Agreement.

The principal aim of this paper is to analyze the second and third elements dealing with the lack of reciprocity in the proposals’ grant of a preferential constitutional veto. The analysis demonstrates the fundamental divisiveness and deep unfairness of these efforts to dismantle the GFA’s majority consent formula. The proposals privilege the constitutional and voting rights of unionists at the same time as they subordinate the corresponding rights of nationalists.

The first proposal to amend the Agreement says that a simple majority in favour of a united Ireland is insufficient. It demands instead that Irish unity be supported by a supermajority in the north. The proposal sees a supermajority as a roundabout or indirect way of ensuring some unionist consent for constitutional change. It expects that the more stringent threshold — something considerably beyond 50 percent + 1 — can be reached only with an acceptable level of unionist support. Former First Minister David Trimble and commentator Andy Pollak justify a supermajority in these terms (Hansard, 1998; Pollak, 2021). Similarly, Irish political scientist Michael Gallagher supports a supermajority in order to prevent the nationalist community from pushing through constitutional change on its own (Gallagher, 2020).

While everyone recognizes that a supermajority is “bigger” than a simple majority, not everyone is sure just how much bigger it should be. Pollak, for instance, does not specify what a supermajority might mean as a percentage in a border poll. O’Leary finds that, generally, qualified majorities (supermajorities) are usually set at 60 or 66 percent (O’Leary, 2021). In the period leading up to the Agreement, Democratic Dialogue called for an overall supermajority of 70 percent to guarantee majority support in both Protestant and Catholic communities (Democratic Dialogue, 1997). Its figure of 70 percent is based on older demographic weights showing a greater Protestant-Catholic dominance than exists today.[2]

Defining a supermajority as 60 percent of all voters would probably be acceptable to most commentators who propose this kind of change. Trimble sets the level at 60 percent because it resonates with the GFA’s provision for a “weighted majority” in key Assembly decisions requiring cross-community support. Gallagher too mentions that “perhaps 60 per cent” might suffice as a workable definition of a supermajority (Gallagher, 2020).

The second proposal addresses the question of unionist support more directly than does the roundabout method of supermajority. It declares explicitly that a majority of unionists must consent to a united Ireland. This proposal is based on Seamus Mallon’s call for amending the border-poll provisions of the GFA.[3] Mallon, much like Trimble before him, invokes the Agreement’s consociational provisions for cross-community support. He asks:

Parallel consent in the Assembly requires majority support among both nationalist and unionist MLAs. In applying this Assembly condition to the arena of constitutional change, Mallon seems to be saying that a majority of unionist voters must support the unity option in a border poll. Brendan O’Leary interprets Mallon’s position in exactly this way (O’Leary, 2021).

The third proposal, like the second, is a direct approach to community approval. It sets significant unionist support, not necessarily majority unionist support, as the threshold of constitutional change. This proposal emerges from an interpretation of Mallon’s work that differs from the one O’Leary uses. Mallon isn’t tied to the requirement of majority unionist consent. He allows a looser threshold. He says that Irish unity “would ... require a majority — or at least 40 per cent support — within the unionist community” (Mallon, 2019, loc. 3867, my emphasis). There is no need to conflate Mallon’s two thresholds, which are a source of confusion in his work.[5] Majority unionist consent is not the same as substantial but minority unionist support. If we allow Mallon’s requirement of majority consent among unionists to define the second proposal, let’s also accept his threshold of at least 40 percent unionist approval to distinguish the third.

Many other prominent figures in Irish political life would alter the GFA in ways consistent with the three proposals outlined above. Former Taoiseach Bertie Ahern implies a supermajority when he says a united Ireland should come about only if it is supported by “a sizeable amount of people on the island of Ireland, North and South” (White, 2008). But he also invokes the need for explicit cross-community consent:

In summary, the three proposals establish different but related conditions for determining if the Irish unity option wins a border poll in the north. All the conditions rupture the Agreement’s formula of majority consent for constitutional change. The core of each proposal can be represented as follows:

Proposal 1: unity must be supported by a supermajority of at least 60 percent of all voters;

Proposal 2: unity must be supported by a majority of at least 50 percent + 1 of unionist voters;

Proposal 3: unity must be supported by a substantial number of at least 40 percent of unionist voters.

I’ll focus on these core conditions, but the proposals have ancillary characteristics too. Proposals 2 and 3 generally assume that unity is also supported by a majority of all voters. These two proposals face the considerable difficulty of working out how to identify unionist voters in a border poll so that their votes can be separately counted against the threshold of community consent.[8] Proposal 1’s indirect route of ensuring some unionist support through a supermajority circumvents this problem of registering the community identity of voters. Each proposal takes for granted that the level of unionist support is at least matched by the level of nationalist support. And the proposals are not independent of each other. All the proposals could overlap in the sense that a single referendum outcome could meet every specified condition.

The reciprocal Test On The Constitutional Status Quo

Justice Humphreys believes that the 50 percent + 1 rule for constitutional change, so maligned by many of the critics proposing to alter it, is actually part of “the genius of the Agreement” (Humphreys, 2018, p. 92). He shows that the simple majority formula is rooted in the equal treatment of both main constitutional communities and underpinned by the GFA’s ethos of parity of esteem. Any deviation from the Agreement’s formula will necessarily result in the unequal treatment of one community and the weakening of parity of esteem.

Humphreys develops “a reciprocal test” that I’ll use to expose the undemocratic and inegalitarian implications of the three proposals to alter the Agreement’s majority consent formula. The reciprocal test is straightforward:

The reciprocal test is especially insightful because it highlights the close procedural interconnection between changing and maintaining the constitutional status quo. It insists that the fairness of any rule for changing the north’s constitutional status to “part of a united Ireland” must be assessed against how that same rule would perform for maintaining the north’s constitutional status as “part of the United Kingdom.” The reciprocal test demands that, under circumstances of both constitutional change and constitutional stability, the rule treat unionists and nationalists equally (Burke, 2017).

Let’s ask the three proposals to sit down and take the reciprocal test on the constitutional status quo. We need to adjust the proposals to have them describe rules or conditions for maintaining the north’s current status as part of the UK. If, as the proposals suggest, moving to a united Ireland should require a supermajority of all voters or majority unionist consent or significant unionist support, then staying with British sovereignty should require the same levels of support among all voters and nationalists.

The three proposals, adjusted to fit the constitutional status quo, become:

Proposal 1: union must be supported by a supermajority of at least 60 percent of all voters;

Proposal 2: union must be supported by a majority of at least 50 percent + 1 of nationalist voters;

Proposal 3: union must be supported by a substantial number of at least 40 percent of nationalist voters.[9]

Let’s examine the levels of public support for the union since the Agreement was signed in 1998 to see if they meet any of the conditions set out in the adjusted proposals.

Data Analysis

I draw all the data for this analysis from the Northern Ireland Life and Times (NILT) Survey, which has been conducted each year since 1998 except for 2011, when insufficient funding prevented fieldwork from taking place (ARK-NILT, 1998-2020). Set up by Queen’s University Belfast and Ulster University, the NILT is an influential survey that records the political, constitutional and social attitudes of people in the north. The size of the NILT samples varies, from about 1800 respondents in the period 1998 to 2004 to approximately 1200 respondents in subsequent years.

NILT surveys have two features that make them an easy test for finding consent for the union. First, they consistently underrepresent the number of Sinn Féin supporters. In Assembly, Westminster, local and European elections over the past 18 years, Sinn Féin typically wins 24 to 28 percent of the vote.[10] But Sinn Féin supporters make up only 9 to 15 percent of NILT samples in this period. As Sinn Féin partisans have, in almost every survey year, the lowest levels of support for the union compared to other major social and political groups, their underrepresentation in NILT samples will falsely inflate estimates of pro-union sentiment. Second, from 2007 onward, the NILT uses a biased measure of constitutional preference that likely overestimates support for the union. I say more about this issue below. We need to keep in mind these two problematic characteristics of NILT surveys as we assess the extent of public support for the union.

Proposal 1: Is There A Supermajority For Union?

The adjusted version of Proposal 1 demands that a supermajority of at least 60 percent of voters support the union. Figure 1 displays the survey data relevant to the question of supermajorities. It shows, for the years 1998 to 2020, the percentage of all respondents who say that the long-term policy for the north should be for it to remain part of the UK. The calculation of percentages in Figure 1, and in all other figures, includes the full range of responses to the question on long-term constitutional preference. In 1998, for example, 56.6 percent of respondents support the union, 21.9 percent support Irish reunification, 8.8 percent prefer some other constitutional arrangement, and 12.8 percent say they “don’t know.”[11] For the year 1998, the figure records only the 56.6 percent saying that they support maintaining the union. The same holds for all other years.

Let’s examine the occurrence of supermajorities of at least 60 percent in favour of maintaining the union. Figure 1 shows that, from 1998 to 2006, there are no such supermajorities, although the 59.6 percent of all respondents who support the union in 2000 comes very close. The average level of support for the union in these years is 56 percent, a majority to be sure but no supermajority. In 2007, we see a big jump in pro-union support, yielding the first supermajority of 66.3 percent. From then through 2019, there are supermajorities every year, averaging 66 percent. In 2020, support for the union falls to 55 percent.

The sudden appearance and proliferation of supermajorities starting in 2007 need to be interpreted cautiously. In that same year, the NILT changes the question measuring long-term constitutional preference. Prior to 2007, the NILT asks respondents to make a simple choice between two constitutional options: “Do you think the long-term policy for Northern Ireland should be for it to remain part of the United Kingdom or, to reunify with the rest of Ireland?” From 2007 on, it asks respondents to choose one of three options: remaining part of the UK with direct rule, remaining part of the UK with devolved government, or reunifying with Ireland.[12] The revised wording introduces a new imbalance in the question: it gives survey respondents two opportunities to express support for the union—with direct rule or with devolution—but only one opportunity to support Irish unity. The 2007 version of the question very likely creates a response bias in favour of the union. More survey respondents will express support for the union simply because the new question gives them two options to do so (Burke, 2021).

We should keep this bias in mind because, throughout the analysis, long-term support for the union after 2006 is a combination of the two pro-union percentages. In Figure 1, for instance, the 66.3 percent of all respondents who say they favour the union in 2007 is the sum of the 11 percent who support union with direct rule and the 55.3 percent who support it with devolved government. The summed percentage is used in all subsequent years.

Figure 2 gives a quick estimate of how the biased question might affect the appearance of supermajorities favouring the union. The NILT surveys in 2017, 2019 and 2020 include additional questions measuring constitutional preference. Those questions ask respondents how they would vote if a constitutional referendum were held tomorrow.[13] Most importantly, the questions are unbiased in that they give one response option for union and one for unity. Figure 2 shows the percentage of all respondents supporting the union on the unbiased “vote tomorrow” questions and on the biased “long-term preference” question. Vote tomorrow is represented by the grey line, long-term preference by the black.

The size of the gap between the black and grey lines in Figure 2 is a measure of how much the biased question on long-term preference overestimates support for the union compared to the unbiased questions on vote tomorrow. That gap is considerable in 2017 and 2019, reaching almost 10 percentage points in the latter year. The gap narrows in 2020. The most relevant finding in Figure 2 is that the two supermajorities on the biased black line in 2017 and 2019 are reduced to ordinary majorities on the unbiased grey line. Supermajorities seem to be tied to the pro-union bias in the question on long-term constitutional preference.

Together, Figures 1 and 2 indicate that there is only fragile evidence for Proposal 1’s adjusted requirement of supermajorities of at least 60 percent in favour of the union. There are no supermajorities between 1998 and 2006. The supermajorities since 2007 may be largely an artefact of a biased measure that artificially increases support for the union. The unbiased estimates on the grey line in Figure 2 reveal that support for the union is currently hovering close to a simple majority, in the mid to low 50 percent range. A host of other public opinion polls confirms the absence of supermajorities and places recent support for the union around 50 percent (White, 2020; Donaghy, 2020).

Proposals 2 and 3: Is There Nationalist Consent For Union?

Proposal 2 (adjusted) stipulates majority nationalist consent for union, Proposal 3 (adjusted) demands substantial nationalist support of at least 40 percent. Recall that both proposals are confronted by the political and practical problem of ascertaining how to register the community identity of voters in a border poll. Fortunately, the equivalent problem is less challenging, though still a concern, for survey research.[14] Analysts using the NILT datasets can readily distinguish those respondents who are nationalists.

Figure 3 tracks nationalist support for the union since 1998. Nationalists are measured in two ways. First, survey respondents may identify themselves as “nationalist” in answer to the NILT question: “Generally speaking, do you think of yourself as a unionist, a nationalist or neither?” In the analysis below, I refer to this group as those with a nationalist identity or, more simply, as nationalist identifiers. Second, I classify respondents as “nationalist” if they feel closer to or generally support nationalist political parties, in this case Sinn Féin or the SDLP. I label these respondents as nationalist party supporters.[15]

The black line in Figure 3 shows the percentage of nationalist identifiers who prefer the union; the grey line gives the corresponding percentage for nationalist party supporters. The two lines move in unison over the entire period: levelling off, rising and falling together. Overall, nationalist support for the union is very low in the first nine years of the Agreement, rises thereafter, but starts to fall precipitously in 2013-2014. The figure also reveals a difference between the two types of nationalists. The grey line is always above the black line, even if the gap between lines is usually small. In other words, support for the union is uniformly but, in most years, marginally higher among nationalist party supporters than it is among nationalist identifiers. Not surprisingly, there is a strong but not perfect relationship between the constitutional preferences of these two intersecting sets of nationalists. Finally, there is an important internal difference among nationalist party supporters, which is not captured in the figure. In each year, pro-union sentiment is much lower among Sinn Féin voters than it is among SDLP supporters.

To return to the main research question, Figure 3 gives an initial test of Proposals 2 and 3. Proposal 2 (adjusted) requires that 50 percent + 1 of nationalists support the union. This level is reached only once, by nationalist party supporters in 2014. The adjusted version of Proposal 3 specifies that at least 40 percent of nationalists support the north’s current status as part of the UK. Nationalist party supporters show this level of support eight times in the 22 years displayed in the figure. Nationalist identifiers reach the 40 percent figure four times. Both sets of nationalists achieve the required thresholds in the years from 2007 on, during the period in which the NILT asks a biased question on long-term constitutional preference that likely magnifies pro-union opinion. Relatedly, Figure 3 shows a spectacular increase in nationalist support for the union starting in 2007, again when the biased question is in use. For those with a nationalist identity, support for the union grows from 11.4 percent in 2006 to 26.7 percent in 2007 and continues to rise almost every year through 2013, reaching a peak of 45.7 percent in that year. The corresponding increase for nationalist party supporters is from 16.4 percent to 39 percent, with a peak of 51.9 percent support for the union reached in 2014.

There are a number of possible explanations for the higher levels of nationalist support for the union in the 2007-2014 period. But it’s hard to escape the conclusion that this substantial nationalist support is largely manufactured by the pro-union bias in the measure of long-term constitutional preference (Burke, 2021). Before I take up this matter below, I wish to say a little more about another important trend evident in the data.

Figure 3 indicates a stunning collapse of nationalist support for the union from 2013-2014. For nationalist identifiers, support for the union falls from its peak of 45.7 percent in 2013 to just 12.9 percent in 2020, a decrease of almost 33 percentage points. For nationalist party voters, support for the union is more than halved, from 51.9 percent in 2014 to 22.6 percent in 2020. The year 2020 shows the lowest levels of nationalist support for the union in 15 years. We might speculate that the steep decline in support for the union over this period is related to ongoing Brexit crises, the build-up of popular mobilization campaigns calling for a united Ireland and, perhaps, Stormont’s chronic dysfunction and Westminster’s increasingly obvious disarray.[16]

As mentioned above, all the percentages after 2006 in Figure 3 probably overestimate the level of pro-union sentiment because of the biased measure of constitutional preference. Support for the union would be consistently lower — through all the post-2006 ups and downs in the figure — if an unbiased or less biased measure were in use. This realization makes the recent disintegration in nationalist support for the union all the more striking.

Figure 4 points to the impact of question bias on the level of support for the union. It repeats, for nationalist identifiers, the kind of analysis we conducted in Figure 2 for all respondents. Figure 4 compares the level of nationalist support for the union using a biased and unbiased (less biased) measure of constitutional preference. In each of the three years in which both measures are available, the biased measure on the black line shows much higher levels of support for the union than does the unbiased measure on the grey line. In 2019 and 2020, the grey line indicates that support for the union among nationalist identifiers has all but evaporated, decreasing to single digits.

To recapitulate, the last two figures examine directly the adjusted forms of Proposals 2 and 3. Proposal 2 demands majority nationalist consent for union, Proposal 3 significant nationalist support of at least 40 percent. Three major conclusions emerge from the analysis of NILT surveys: (1) there is neither majority nationalist consent nor significant nationalist support for union in the first nine years of the Agreement; (2) the required levels of nationalist support are reached occasionally, but only after the survey begins using a biased measure of constitutional preference that overestimates support for the union; and (3) nationalist support for the union plummets in the last 8 to 10 years, well below the thresholds set by Proposals 2 and 3.

Proposals 2 and 3 fail the reciprocal test even more miserably than does Proposal 1. Since there is no nationalist consent for union, there is correspondingly no democratic or egalitarian justification for the proposals to require unionist consent for unity. If the union can persist without nationalist consent, why must Irish unity await unionist consent?

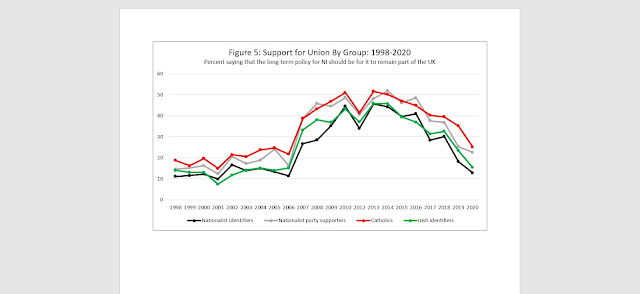

No matter how we define the communities—as nationalist, Catholic or Irish—Proposals 2 and 3 still fail the reciprocal test.

Conclusion: The Ethos of Partition

That northern nationalists do not consent to partition is hardly a new finding. The absence of consent dates from 1921, not from 1998 when my study begins.[18] Generally, the purpose of my analysis is to track empirically the state of public opinion on support for the union since the signing of the Agreement. In particular, it is to use survey data on constitutional preference to assess the political implications of three major proposals to alter the GFA’s simple majority rule for constitutional change.

The essence of the three proposals is to insert a unionist veto over constitutional change. The proposals lack reciprocity in that they fail to provide for an equivalent nationalist veto over maintaining current constitutional arrangements. Their direct and intended effect is to delay or stifle Irish unity without disturbing the union.[19] In fact, the hulking form of the constitutional status quo unmasks a fatal flaw in the proposals’ attempts to alter the rules for establishing a united Ireland.

The data analysis demonstrates that each of the proposals fails the reciprocal test on the constitutional status quo. The data showing that there is no supermajority for union reveal the hollowness of Proposal 1’s demand that there must be a supermajority for unity. The analysis demonstrating that there is no nationalist consent for union uncovers the hypocrisy of Proposal 2’s and Proposal 3’s requirement of unionist consent for unity.

The proposals treat the two constitutional communities unequally and unfairly, privileging unionists and subordinating nationalists. They withhold from nationalists the very rights and powers over constitutional status that they grant to unionists. The proposals place added value on unionist votes while they discount the value of nationalist votes.

These superior-subordinate relations — part of the very structure of the three proposals — are reminiscent of the ethos of partition. Every supporter of the proposals is in effect telling northern nationalists, as the architects of partition told them in 1921, to accept their inferior rank on the constitutional question. The proposals can succeed in their aim of quashing Irish unity only by further normalizing and extending the communal injustice inherent in partition.

Nationalists and republicans might consider posing some tough questions to commentators who continue blithely to peddle the glaring inequality in the three proposals. One question is: why should nationalists be expected to continue living with the same set of constitutional circumstances that unionists should not even have to contemplate?

Notes

[1] I’ve explored these proposals in a different context in Burke (2017 & 2020).

[2] In the 1998 NILT survey, Protestants and Catholics made up 90.8 of the sample; in 2020, they made up only 72 percent. Over the years of the survey, the “no religion” group has tripled in size, from 9.3 percent in 1998 to 28 percent in 2020. These figures are taken from the RELIGCAT variable.

[3] In the years before the Agreement, there were numerous calls to establish unionist majority consent as a precondition of Irish unity (Crick, 1986; Cadogan Group, 1992; Opsahl Inquiry, 1993; Guelke, 1997). These calls can be seen as direct precursors of Mallon’s position.

[4] I’m quoting from the Kindle edition of Mallon’s book A Shared Home Place, which uses location numbers instead of page numbers. Hereafter, I’ll use the abbreviations “loc.” and “locs.”

[5] See Burke (2020) for a detailed critique of Mallon’s proposal.

[6] Ahern’s views here on a supermajority and dual community consent are notably different from his position in 2003, when he praised the constitutional provisions of the GFA: “For the first time, a precise mechanism for achieving a united Ireland, which is possible only with the consent of the Irish people, has been defined and accepted by all sides” (Ahern, 2003, p. 28). Ahern is now suggesting that, in practice, the Agreement’s vaunted “precise mechanism” should be ignored.

[7] The quotation is from Pollak (2017). Pollak’s advocacy of significant or substantial unionist support for Irish reunification has recently evolved. In 2019, he articulates his position in the context of Mallon’s notion of parallel consent (Pollak, 2019). In 2021, he suggests that parallel consent is not a plausible threshold because a majority of unionists will never support Irish unity. He instead requires support from “a significant minority of unionists” as measured by a supermajority in a border poll (Pollak, 2021, p. 12).

[8] Others have pointed to this difficulty (Democratic Dialogue, 1997; SDLP 2020; O’Leary 2021). Mallon acknowledges that the communal registration of voters poses a challenge to his proposal for parallel consent to constitutional change; but he does not squarely face the matter (Mallon, 2019, loc. 4092).

[9] O’Leary applies the reasoning of the reciprocal test to the supermajority threshold (Proposal 1): “A change to require a qualified majority [supermajority] vote for the north to reunify with Ireland should logically require that a qualified majority vote be required to sustain the status quo” (O’Leary, 2021, p. 9). Humphreys applies such reasoning in examining the case for unionist consent to constitutional change (Proposals 2 and 3): “... the really fundamental reason ... why a minority or a dual consent requirement could never act to prevent the reunification of the island of Ireland if a majority so wished, is that there is no corresponding provision at present permitting the nationalist and republican ‘minority’ to prevent Northern Ireland from remaining part of the United Kingdom” (Humphreys, 2009, p. xxi). That is, both authors employ the same logic that I use in adjusting the three proposals.

[10] These figures refer to valid votes in Westminster elections and to first preference votes in Assembly, local and European elections.

[11] The 1998 percentages do not sum exactly to 100 percent because of rounding error. In some surveys after 2006, there are a small number of respondents who do not answer or refuse to answer the question on long-term constitutional preference. The NILT datasets define these responses as “missing data” and they are not included in the calculation of percentages in the figures. There are so few respondents in this category, averaging only 8 people (0.7%) across the relevant NILT samples, that their exclusion from the analysis does not materially alter the percentages shown in the figures or the substance of the conclusions drawn from those figures.

[12] For those familiar with the NILT data or who might examine the data tables published on the NILT website, the change of question in 2007 is associated with a change in the name of the variable. NIRELAND is the name of the variable measuring long-term constitutional preference from 1998 to 2006. The new variable NIRELND2 appears in 2007 to reflect the new response options.

[13] The names of the “vote tomorrow” variables in Figure 2 are BORDPOLL (2017) and REFUNIFY (2019 and 2020). BORDPOLL is based on the question: “If there was a referendum tomorrow about whether Northern Ireland should leave the UK and unite with the Republic of Ireland, how do you think you would vote? I would vote for Northern Ireland to remain part of the UK; I would vote for Northern Ireland to unite with the Republic of Ireland; I wouldn’t vote; I don’t know.” REFUNIFY is from the question: “Suppose there was a referendum tomorrow on the future of Northern Ireland and you were

being asked to vote on whether Northern Ireland should unify with the Republic of Ireland. Would you vote ‘yes’ to unify with the Republic or ‘no’? Yes, should unify with the Republic; No, should not unify with the Republic.”

[14] Survey researchers need to be aware of the validity and reliability of their measures. Figure 3 uses standard measures of nationalism whose validity and reliability should not be a problem.

[15] Nationalist identity is the variable UNINATID. NILT designers have constructed three comparable measures of party support that are used in different years: NIPARTY (1998-2006), POLPARTY (2007 and 2008), and POLPART2 (2009-2020). As mentioned in the text, nationalist party supporters are defined as those who support Sinn Féin or the SDLP.

[16] Garry et al. find that concern about a hard Brexit is one major factor decreasing Catholics’ support for the union and increasing their support for Irish unity (Garry et al., 2020). The Working Group on Unification Referendums on the Island of Ireland also finds that Brexit is a principal driver of opinion on constitutional preference (Working Group, 2021).

[17] The NILT measures this form of identity with the following question: “Which of these best describes the way you think of yourself? British, Irish, Ulster, Northern Irish, Other.” The name of this variable in the NILT datasets is NINATID. Religion is measured with the variable RELIGCAT (see note 2).

[18] Richard Rose’s 1968 loyalty survey finds that 33 percent of Catholics support the union. The Northern Ireland Social Attitudes surveys, conducted from the late 1980s through the mid-1990s, also record roughly one-third support among Catholics (Rose, 1971, p. 477; ARK-SOL, 1989-1996). This level of support for the union is higher than that for the first nine years of the Agreement (Figure 5) but still well below the thresholds specified by Proposals 2 and 3. John Coakley has constructed a new measure of constitutional preference from Rose’s data that puts Catholic support for the union at 42 percent in 1968, just above Proposal 3’s threshold (Coakley, 2021). Eamon Phoenix examines the historical lack of northern nationalist consent for the union, pointing to “the trauma of the partition of Ireland for the nationalist minority, now marooned against their will in a Unionist-dominated state” (Phoenix, 1994, p. xvii).

[19] Some commentators who apply reciprocal logic to the constitutional here and now point out that the absence of a pro-union supermajority or the lack of nationalist consent for the union could imply moving to joint British-Irish sovereignty or creating a new bespoke constitutional status for the north (O’Leary, 2021; Democratic Dialogue, 1997). The main champions of the proposals, however, are not interested in pursuing this route because they seem equally motivated both by blocking change and preserving the status quo. For them, the existing constitutional regime must remain intact, no matter what nationalists think or fairness demands.

References

Ahern, B. (2003): “In Search of Peace: The Fate and Legacy of the Good Friday Agreement.” Harvard International Review 24:4 (Winter): 26-31.

ARK-NILT. (1998-2020). Northern Ireland Life and Times Survey. Retrieved from: www.ark.ac.uk/nilt.

ARK-SOL (1989-1996). Surveys Online, Northern Ireland Social Attitudes Survey. Retrieved from https://www.ark.ac.uk/sol/nisa.html.

Burke, M. (2017). “Deepening the Unionist Veto,” The Pensive Quill. 1 November. Retrieved from http://thepensivequill.am/2017/11/deepening-unionist-veto.html

Burke, M. (2020). “Stealing Irish Unity: The Repertoire of Thieves.” The Pensive Quill. [This piece is posted in five parts on September 5, 12, 19, 26 and October 3. All five parts can be retrieved from https://www.thepensivequill.com].

Burke, M. (2021). “Up with Union, Down with Unity: Measuring Constitutional Preference.” The Pensive Quill. 29 May. Retrieved from https://www.thepensivequill.com/2021/05/up-with-union-down-with-unity-measuring.html

Cadogan Group (1992). “Northern Limits: The Boundaries of the Attainable in Northern Ireland Politics.” November. Retrieved from https://thecadogangroup.webs.com/northernlimits.htm

Coakley, J. (2021). Personal communication. 20 August.

Corcoran, J. (2017a). “Sinn Féin’s push for border poll ‘alarming’, says Varadkar.” Irish Independent. 2 April. Retrieved from https://www.independent.ie/irish-news/politics/sinn-feins-push-for-border-poll-alarming-says-varadkar-35585809.html

Corcoran, J. (2017b). “Brian Hayes says ‘fascist IRA’ lost to Sean O’Callaghan; Flanagan warns ‘premature’ United Ireland talks is ‘dangerous’.” Irish Independent. 27 August. Retrieved from https://www.independent.ie/irish-news/politics/brian-hayes-says-fascist-ira-lost-to-sean-ocallaghan-36072650.html

Crick, B. (1986). “Northern Ireland and the Concept of Consent.” In Public Law and Politics. ed. C. Harlow, 39-56. London: Sweet & Maxwell.

Democratic Dialogue. (1997). “Making 'consent' mutual - A discussion paper from Democratic Dialogue.” October. Retrieved from https://cain.ulster.ac.uk/dd/papers/consent.htm

De Rossa, P. (2021). “Debate on unity is divisive and distracting.” Irish Times, Letter to the Editor. 12 August. Retrieved from the Factiva (Dow Jones) electronic database of new articles [cited below as Factiva].

Donaghy, P. (2020). “The mystery of the ‘shy nationalists’—online and face-to-face polling on Irish unity continues to give different results.” Slugger O’Toole. 19 February. Retrieved from https://sluggerotoole.com/2020/02/19/the-mystery-of-the-shy-nationalists-online-and-face-to-face-polling-on-irish-unity-continues-to-give-different-results/

Donlon. S. (2017). “Sinn Féin missing a lifetime opportunity to set the agenda.” Irish Times. 1 August. Retrieved from https://www.irishtimes.com/opinion/sinn-f%C3%A9in-missing-a-lifetime-opportunity-to-set-the-agenda-1.3172566

Foster, J.W. (2018). “Until the silenced centre, unionist and nationalist alike, can have a conversation about what sort of future they want, a border poll will remain the ultimate polarising catastrophe.” Belfast Telegraph. 17 September. Retrieved from Factiva.

Gallagher, M. (2020). “Submission to Working Group on Unification Referendums on the Island of Ireland.” January. Retrieved from https://www.ucl.ac.uk/constitution-unit/research/elections-and-referendums/working-group-unification-referendums-island-ireland/evidence

Garry, J., B. O’Leary, K. McNicholl and J. Pow. (2020). “The future of Northern Ireland: border anxieties and support for Irish reunification under varieties of UKexit.” Regional Studies. Early view. DOI: 10.1080/00343404.2020.1759796

Guelke, A. (1997). "Consenting to Agreement," Fortnight 366 (November): 12-13.

Hadden, T. (2020). “Plus ça change ... or do we really need to decide now?” Fortnight 479 (September): 8-11. Retrieved from https://fortnightmagazine.org/issues/

Hansard. (1998). House of Commons Debates vol 316 cols 1188-223. 22 July. Retrieved from https://api.parliament.uk/historic-hansard/commons/1998/jul/22/status-of-northern-ireland

Humphreys, R. (2009). Countdown to Unity: Debating Irish Reunification. Dublin and Portland: Irish Academic Press.

Humphreys, R. (2018). Beyond the Border: The Good Friday Agreement and Irish Unity after Brexit. Newbridge, Co. Kildare: Merrion Press.

Kelly, T. (2017). “Opinion – Minority coalition better than DUP and Tories in charge.” Irish News. 4 September. Retrieved from Factiva.

Mallon, S. (2019). With A. Pollak. A Shared Home Place. Kindle ed. Dublin: Lilliput Press.

Millar, F. (2002). “NI accord – back to drawing board?” Irish Times. 25 October. Retrieved from Factiva.

O’Leary, B. (2021). “Getting Ready: The Need to Prepare for a Referendum on Reunification.” Irish Studies in International Affairs 32:2, 1-38. Retrieved from https://www.jstor.org/stable/10.3318/irisstudinteaffa.32.issue-2

Opsahl Inquiry. (1993). A Citizens’ Inquiry: The Opsahl Report on Northern Ireland. ed. A. Pollak. Dublin: Lilliput Press for Initiative ’92.

O’Toole, F. (2017). “EU backing for Irish unity after Brexit is a big deal—but it’s not a solution.” Guardian. 4 May. Retrieved from https://www.theguardian.com/commentisfree/2017/may/04/eu-irish-unity-brexit-europe-northern-ireland

Phoenix, E. (1994). Northern Nationalism: Nationalist Politics, Partition and the Catholic Minority in Northern Ireland, 1890-1940. Belfast: Ulster Historical Foundation.

Pollak, A. (2017). “Nationalism by numbers.” Irish Times, Letter to the Editor. 9 June. Retrieved from https://www.irishtimes.com/opinion/letters/nationalism-by-numbers-1.3112636

Pollak, A. (2019). “Introduction.” In A Shared Home Place by S. Mallon with A. Pollak. Kindle ed. Dublin: Lilliput Press.

Pollak, A. (2021). “Why I don’t believe in Border Polls.” Fortnight 481 (April): 11-13. Retrieved from https://fortnightmagazine.org/issues/

Rose, R. (1971). Governing Without Consensus: An Irish Perspective. London: Faber and Faber Limited.

RTÉ. (2017). “Brexit challenge difficult but not insurmountable – Ahern.” 6 April. Retrieved from https://www.rte.ie/news/brexit/2017/0406/865735-brexit/#

SDLP. (2020). “Submission to the Working Group on Unification Referendums on the Island of Ireland.” September. Retrieved from https://www.ucl.ac.uk/constitution-unit/research/elections-and-referendums/working-group-unification-referendums-island-ireland/evidence

White, B. (2020). “Poll variations on unity are not that surprising.” Irish News. 28 April. Retrieved from Factiva.

White, L. (2008). “Unity needs more than 51% majority: Ahern.” Belfast Telegraph. 20 November. Retrieved from Factiva.

Working Group. (2021). Final Report. Working Group on Unification Referendums on the Island of Ireland. The Constitution Unit, School of Public Policy, University College London. May. Retrieved from https://www.ucl.ac.uk/constitution-unit/working-group-unification-referendums-island-ireland

Brendan O’Leary recently explored plausible demographic and political futures that point out the many problems with proposals to alter the GFA’s formula for constitutional change (O’Leary, 2021). Here, I use survey data over the past 23 years to show that the lived constitutional experiences of northern nationalists and republicans also point to the exceptionally problematic nature of the proposals.

The Proposals

The three proposals to change the Agreement’s simple majority formula have a number of major elements in common. First, they are contemptuously dismissive of the 50 percent + 1 rule, referring to it variously as old, ugly, undesirable, sectarian, crude and tribal (Burke, 2017). Second, their suggested replacement formulas increase unionist control over the constitutional status of the north by inserting a form of unionist veto over Irish unity. Third, the proposals fail to grant nationalists a reciprocal veto over maintaining the union. And fourth, they cavalierly reverse the democratic ratification of the Agreement in the referendums in May 1998. Since the GFA was endorsed by voters north and south, any fundamental change to its terms must also be popularly approved. All the proposals fail to recognize this basic democratic imperative. They would amend a very cornerstone of the GFA — its constitutional provisions — over the heads of voters, thereby estranging the people from the Agreement.

The principal aim of this paper is to analyze the second and third elements dealing with the lack of reciprocity in the proposals’ grant of a preferential constitutional veto. The analysis demonstrates the fundamental divisiveness and deep unfairness of these efforts to dismantle the GFA’s majority consent formula. The proposals privilege the constitutional and voting rights of unionists at the same time as they subordinate the corresponding rights of nationalists.

The first proposal to amend the Agreement says that a simple majority in favour of a united Ireland is insufficient. It demands instead that Irish unity be supported by a supermajority in the north. The proposal sees a supermajority as a roundabout or indirect way of ensuring some unionist consent for constitutional change. It expects that the more stringent threshold — something considerably beyond 50 percent + 1 — can be reached only with an acceptable level of unionist support. Former First Minister David Trimble and commentator Andy Pollak justify a supermajority in these terms (Hansard, 1998; Pollak, 2021). Similarly, Irish political scientist Michael Gallagher supports a supermajority in order to prevent the nationalist community from pushing through constitutional change on its own (Gallagher, 2020).

While everyone recognizes that a supermajority is “bigger” than a simple majority, not everyone is sure just how much bigger it should be. Pollak, for instance, does not specify what a supermajority might mean as a percentage in a border poll. O’Leary finds that, generally, qualified majorities (supermajorities) are usually set at 60 or 66 percent (O’Leary, 2021). In the period leading up to the Agreement, Democratic Dialogue called for an overall supermajority of 70 percent to guarantee majority support in both Protestant and Catholic communities (Democratic Dialogue, 1997). Its figure of 70 percent is based on older demographic weights showing a greater Protestant-Catholic dominance than exists today.[2]

Defining a supermajority as 60 percent of all voters would probably be acceptable to most commentators who propose this kind of change. Trimble sets the level at 60 percent because it resonates with the GFA’s provision for a “weighted majority” in key Assembly decisions requiring cross-community support. Gallagher too mentions that “perhaps 60 per cent” might suffice as a workable definition of a supermajority (Gallagher, 2020).

The second proposal addresses the question of unionist support more directly than does the roundabout method of supermajority. It declares explicitly that a majority of unionists must consent to a united Ireland. This proposal is based on Seamus Mallon’s call for amending the border-poll provisions of the GFA.[3] Mallon, much like Trimble before him, invokes the Agreement’s consociational provisions for cross-community support. He asks:

whether this clause of the Good Friday Agreement, Parallel Consent in the Northern Ireland Assembly, could be extended across into the constitutional space and thus be used to protect unionists if a future Border Poll were to result in a narrow overall majority for a united Ireland, but without the consent of both traditions in the North. (Mallon, 2019, location 3488).[4]

Parallel consent in the Assembly requires majority support among both nationalist and unionist MLAs. In applying this Assembly condition to the arena of constitutional change, Mallon seems to be saying that a majority of unionist voters must support the unity option in a border poll. Brendan O’Leary interprets Mallon’s position in exactly this way (O’Leary, 2021).

The third proposal, like the second, is a direct approach to community approval. It sets significant unionist support, not necessarily majority unionist support, as the threshold of constitutional change. This proposal emerges from an interpretation of Mallon’s work that differs from the one O’Leary uses. Mallon isn’t tied to the requirement of majority unionist consent. He allows a looser threshold. He says that Irish unity “would ... require a majority — or at least 40 per cent support — within the unionist community” (Mallon, 2019, loc. 3867, my emphasis). There is no need to conflate Mallon’s two thresholds, which are a source of confusion in his work.[5] Majority unionist consent is not the same as substantial but minority unionist support. If we allow Mallon’s requirement of majority consent among unionists to define the second proposal, let’s also accept his threshold of at least 40 percent unionist approval to distinguish the third.

Many other prominent figures in Irish political life would alter the GFA in ways consistent with the three proposals outlined above. Former Taoiseach Bertie Ahern implies a supermajority when he says a united Ireland should come about only if it is supported by “a sizeable amount of people on the island of Ireland, North and South” (White, 2008). But he also invokes the need for explicit cross-community consent:

The only time in my view ... we should have a border poll is when the nationalists and republicans, and a respectable sizeable amount of unionists and loyalists are in favour and on the basis of consent” (RTÉ, 2017).[6]

Tánaiste Leo Varadkar espouses similar sentiments. While running for the leadership of Fine Gael, he called for “unity among people” as a prerequisite of territorial unity, and warned against “bouncing Ulster Protestants into a unitary Irish state against their will.” He emphasized that: “Real lasting workable unity can only come about with a decent measure of support from both communities” (Corcoran, 2017a).

Similar proposals abound. Frank Millar, former northern editor of the Irish Times, says Irish unity should be supported by a majority of unionists (Millar, 2002). Fortnight editor and long-time analyst Tom Hadden advises that a border poll be delayed and that the constitutional status quo stay in place “until there is clear [majority] support for a change in sovereignty in the unionist community” (Hadden, 2020, p. 9). Andy Pollak continues repeatedly to call for “some significant element of unionist consent” to a united Ireland (Pollak, 2017, 2019 & 2021).[7] Former Foreign Affairs minister Charlie Flanagan and journalist Tom Kelly suggest that unity is dependent on winning over the “hearts and minds” of the unionist community (Corcoran, 2017b; Kelly, 2017). Likewise, columnist Fintan O’Toole wants a united Ireland to wait until the consent of “a million unionists” is secured (O’Toole, 2017). Sean Donlon, former Secretary General of the Department of Foreign Affairs, says there is no attraction for “unity by numbers” without unionist consent (Donlon, 2017). Academic JW Foster and former TD and MEP Proinsias De Rossa are representative of many voices urging that constitutional change proceed by “broad consensus” (Foster, 2018; De Rossa, 2021).

The three proposals are a fair depiction of these myriad calls to abandon the GFA’s majority consent rule. My rendering of the proposals forces some precision on what are often inexact formulations. But precision is necessary to make sense of the proposals. Vague descriptions such as “sizeable amount,” “decent measure,” “significant element,” “winning hearts and minds” and “broad consensus” are no help in interpreting the outcome of a referendum on constitutional change. In a border poll, voters need to know the exact percentage separating success from failure.

Similar proposals abound. Frank Millar, former northern editor of the Irish Times, says Irish unity should be supported by a majority of unionists (Millar, 2002). Fortnight editor and long-time analyst Tom Hadden advises that a border poll be delayed and that the constitutional status quo stay in place “until there is clear [majority] support for a change in sovereignty in the unionist community” (Hadden, 2020, p. 9). Andy Pollak continues repeatedly to call for “some significant element of unionist consent” to a united Ireland (Pollak, 2017, 2019 & 2021).[7] Former Foreign Affairs minister Charlie Flanagan and journalist Tom Kelly suggest that unity is dependent on winning over the “hearts and minds” of the unionist community (Corcoran, 2017b; Kelly, 2017). Likewise, columnist Fintan O’Toole wants a united Ireland to wait until the consent of “a million unionists” is secured (O’Toole, 2017). Sean Donlon, former Secretary General of the Department of Foreign Affairs, says there is no attraction for “unity by numbers” without unionist consent (Donlon, 2017). Academic JW Foster and former TD and MEP Proinsias De Rossa are representative of many voices urging that constitutional change proceed by “broad consensus” (Foster, 2018; De Rossa, 2021).

The three proposals are a fair depiction of these myriad calls to abandon the GFA’s majority consent rule. My rendering of the proposals forces some precision on what are often inexact formulations. But precision is necessary to make sense of the proposals. Vague descriptions such as “sizeable amount,” “decent measure,” “significant element,” “winning hearts and minds” and “broad consensus” are no help in interpreting the outcome of a referendum on constitutional change. In a border poll, voters need to know the exact percentage separating success from failure.

In summary, the three proposals establish different but related conditions for determining if the Irish unity option wins a border poll in the north. All the conditions rupture the Agreement’s formula of majority consent for constitutional change. The core of each proposal can be represented as follows:

Proposal 1: unity must be supported by a supermajority of at least 60 percent of all voters;

Proposal 2: unity must be supported by a majority of at least 50 percent + 1 of unionist voters;

Proposal 3: unity must be supported by a substantial number of at least 40 percent of unionist voters.

I’ll focus on these core conditions, but the proposals have ancillary characteristics too. Proposals 2 and 3 generally assume that unity is also supported by a majority of all voters. These two proposals face the considerable difficulty of working out how to identify unionist voters in a border poll so that their votes can be separately counted against the threshold of community consent.[8] Proposal 1’s indirect route of ensuring some unionist support through a supermajority circumvents this problem of registering the community identity of voters. Each proposal takes for granted that the level of unionist support is at least matched by the level of nationalist support. And the proposals are not independent of each other. All the proposals could overlap in the sense that a single referendum outcome could meet every specified condition.

The reciprocal Test On The Constitutional Status Quo

Justice Humphreys believes that the 50 percent + 1 rule for constitutional change, so maligned by many of the critics proposing to alter it, is actually part of “the genius of the Agreement” (Humphreys, 2018, p. 92). He shows that the simple majority formula is rooted in the equal treatment of both main constitutional communities and underpinned by the GFA’s ethos of parity of esteem. Any deviation from the Agreement’s formula will necessarily result in the unequal treatment of one community and the weakening of parity of esteem.

Humphreys develops “a reciprocal test” that I’ll use to expose the undemocratic and inegalitarian implications of the three proposals to alter the Agreement’s majority consent formula. The reciprocal test is straightforward:

… the test for a united Ireland must correspond to that required for a United Kingdom, subject to the rider that agreement is also required in a referendum in the South.

The test for a United Kingdom is the support of ‘a majority’—in a democracy that is 50 per cent + 1 of those present and validly voting. That consent will remain effective even if it is a bare majority of one. On the principle of equal and reciprocal respect, the test for a united Ireland cannot be any more difficult. 50 per cent + 1 of those present and validly voting in referenda North and South is legally sufficient to trigger Irish unity. Generally, people who say that one cannot coerce hundreds of thousands of unionists into a united Ireland have no real problem with coercing hundreds of thousands of nationalists into a United Kingdom. If one takes equal respect seriously, one has to accept the consequences of a reciprocal test (Humphreys, 2018, pp. 84 & 85).

Let’s ask the three proposals to sit down and take the reciprocal test on the constitutional status quo. We need to adjust the proposals to have them describe rules or conditions for maintaining the north’s current status as part of the UK. If, as the proposals suggest, moving to a united Ireland should require a supermajority of all voters or majority unionist consent or significant unionist support, then staying with British sovereignty should require the same levels of support among all voters and nationalists.

The three proposals, adjusted to fit the constitutional status quo, become:

Proposal 1: union must be supported by a supermajority of at least 60 percent of all voters;

Proposal 2: union must be supported by a majority of at least 50 percent + 1 of nationalist voters;

Proposal 3: union must be supported by a substantial number of at least 40 percent of nationalist voters.[9]

Let’s examine the levels of public support for the union since the Agreement was signed in 1998 to see if they meet any of the conditions set out in the adjusted proposals.

Data Analysis

I draw all the data for this analysis from the Northern Ireland Life and Times (NILT) Survey, which has been conducted each year since 1998 except for 2011, when insufficient funding prevented fieldwork from taking place (ARK-NILT, 1998-2020). Set up by Queen’s University Belfast and Ulster University, the NILT is an influential survey that records the political, constitutional and social attitudes of people in the north. The size of the NILT samples varies, from about 1800 respondents in the period 1998 to 2004 to approximately 1200 respondents in subsequent years.

NILT surveys have two features that make them an easy test for finding consent for the union. First, they consistently underrepresent the number of Sinn Féin supporters. In Assembly, Westminster, local and European elections over the past 18 years, Sinn Féin typically wins 24 to 28 percent of the vote.[10] But Sinn Féin supporters make up only 9 to 15 percent of NILT samples in this period. As Sinn Féin partisans have, in almost every survey year, the lowest levels of support for the union compared to other major social and political groups, their underrepresentation in NILT samples will falsely inflate estimates of pro-union sentiment. Second, from 2007 onward, the NILT uses a biased measure of constitutional preference that likely overestimates support for the union. I say more about this issue below. We need to keep in mind these two problematic characteristics of NILT surveys as we assess the extent of public support for the union.

Proposal 1: Is There A Supermajority For Union?

The adjusted version of Proposal 1 demands that a supermajority of at least 60 percent of voters support the union. Figure 1 displays the survey data relevant to the question of supermajorities. It shows, for the years 1998 to 2020, the percentage of all respondents who say that the long-term policy for the north should be for it to remain part of the UK. The calculation of percentages in Figure 1, and in all other figures, includes the full range of responses to the question on long-term constitutional preference. In 1998, for example, 56.6 percent of respondents support the union, 21.9 percent support Irish reunification, 8.8 percent prefer some other constitutional arrangement, and 12.8 percent say they “don’t know.”[11] For the year 1998, the figure records only the 56.6 percent saying that they support maintaining the union. The same holds for all other years.

Let’s examine the occurrence of supermajorities of at least 60 percent in favour of maintaining the union. Figure 1 shows that, from 1998 to 2006, there are no such supermajorities, although the 59.6 percent of all respondents who support the union in 2000 comes very close. The average level of support for the union in these years is 56 percent, a majority to be sure but no supermajority. In 2007, we see a big jump in pro-union support, yielding the first supermajority of 66.3 percent. From then through 2019, there are supermajorities every year, averaging 66 percent. In 2020, support for the union falls to 55 percent.

The sudden appearance and proliferation of supermajorities starting in 2007 need to be interpreted cautiously. In that same year, the NILT changes the question measuring long-term constitutional preference. Prior to 2007, the NILT asks respondents to make a simple choice between two constitutional options: “Do you think the long-term policy for Northern Ireland should be for it to remain part of the United Kingdom or, to reunify with the rest of Ireland?” From 2007 on, it asks respondents to choose one of three options: remaining part of the UK with direct rule, remaining part of the UK with devolved government, or reunifying with Ireland.[12] The revised wording introduces a new imbalance in the question: it gives survey respondents two opportunities to express support for the union—with direct rule or with devolution—but only one opportunity to support Irish unity. The 2007 version of the question very likely creates a response bias in favour of the union. More survey respondents will express support for the union simply because the new question gives them two options to do so (Burke, 2021).

|

| *I examine the wording of this question in the text. |

We should keep this bias in mind because, throughout the analysis, long-term support for the union after 2006 is a combination of the two pro-union percentages. In Figure 1, for instance, the 66.3 percent of all respondents who say they favour the union in 2007 is the sum of the 11 percent who support union with direct rule and the 55.3 percent who support it with devolved government. The summed percentage is used in all subsequent years.

Figure 2 gives a quick estimate of how the biased question might affect the appearance of supermajorities favouring the union. The NILT surveys in 2017, 2019 and 2020 include additional questions measuring constitutional preference. Those questions ask respondents how they would vote if a constitutional referendum were held tomorrow.[13] Most importantly, the questions are unbiased in that they give one response option for union and one for unity. Figure 2 shows the percentage of all respondents supporting the union on the unbiased “vote tomorrow” questions and on the biased “long-term preference” question. Vote tomorrow is represented by the grey line, long-term preference by the black.

The size of the gap between the black and grey lines in Figure 2 is a measure of how much the biased question on long-term preference overestimates support for the union compared to the unbiased questions on vote tomorrow. That gap is considerable in 2017 and 2019, reaching almost 10 percentage points in the latter year. The gap narrows in 2020. The most relevant finding in Figure 2 is that the two supermajorities on the biased black line in 2017 and 2019 are reduced to ordinary majorities on the unbiased grey line. Supermajorities seem to be tied to the pro-union bias in the question on long-term constitutional preference.

Together, Figures 1 and 2 indicate that there is only fragile evidence for Proposal 1’s adjusted requirement of supermajorities of at least 60 percent in favour of the union. There are no supermajorities between 1998 and 2006. The supermajorities since 2007 may be largely an artefact of a biased measure that artificially increases support for the union. The unbiased estimates on the grey line in Figure 2 reveal that support for the union is currently hovering close to a simple majority, in the mid to low 50 percent range. A host of other public opinion polls confirms the absence of supermajorities and places recent support for the union around 50 percent (White, 2020; Donaghy, 2020).

Proposals 2 and 3: Is There Nationalist Consent For Union?

Proposal 2 (adjusted) stipulates majority nationalist consent for union, Proposal 3 (adjusted) demands substantial nationalist support of at least 40 percent. Recall that both proposals are confronted by the political and practical problem of ascertaining how to register the community identity of voters in a border poll. Fortunately, the equivalent problem is less challenging, though still a concern, for survey research.[14] Analysts using the NILT datasets can readily distinguish those respondents who are nationalists.

Figure 3 tracks nationalist support for the union since 1998. Nationalists are measured in two ways. First, survey respondents may identify themselves as “nationalist” in answer to the NILT question: “Generally speaking, do you think of yourself as a unionist, a nationalist or neither?” In the analysis below, I refer to this group as those with a nationalist identity or, more simply, as nationalist identifiers. Second, I classify respondents as “nationalist” if they feel closer to or generally support nationalist political parties, in this case Sinn Féin or the SDLP. I label these respondents as nationalist party supporters.[15]

The black line in Figure 3 shows the percentage of nationalist identifiers who prefer the union; the grey line gives the corresponding percentage for nationalist party supporters. The two lines move in unison over the entire period: levelling off, rising and falling together. Overall, nationalist support for the union is very low in the first nine years of the Agreement, rises thereafter, but starts to fall precipitously in 2013-2014. The figure also reveals a difference between the two types of nationalists. The grey line is always above the black line, even if the gap between lines is usually small. In other words, support for the union is uniformly but, in most years, marginally higher among nationalist party supporters than it is among nationalist identifiers. Not surprisingly, there is a strong but not perfect relationship between the constitutional preferences of these two intersecting sets of nationalists. Finally, there is an important internal difference among nationalist party supporters, which is not captured in the figure. In each year, pro-union sentiment is much lower among Sinn Féin voters than it is among SDLP supporters.

To return to the main research question, Figure 3 gives an initial test of Proposals 2 and 3. Proposal 2 (adjusted) requires that 50 percent + 1 of nationalists support the union. This level is reached only once, by nationalist party supporters in 2014. The adjusted version of Proposal 3 specifies that at least 40 percent of nationalists support the north’s current status as part of the UK. Nationalist party supporters show this level of support eight times in the 22 years displayed in the figure. Nationalist identifiers reach the 40 percent figure four times. Both sets of nationalists achieve the required thresholds in the years from 2007 on, during the period in which the NILT asks a biased question on long-term constitutional preference that likely magnifies pro-union opinion. Relatedly, Figure 3 shows a spectacular increase in nationalist support for the union starting in 2007, again when the biased question is in use. For those with a nationalist identity, support for the union grows from 11.4 percent in 2006 to 26.7 percent in 2007 and continues to rise almost every year through 2013, reaching a peak of 45.7 percent in that year. The corresponding increase for nationalist party supporters is from 16.4 percent to 39 percent, with a peak of 51.9 percent support for the union reached in 2014.

There are a number of possible explanations for the higher levels of nationalist support for the union in the 2007-2014 period. But it’s hard to escape the conclusion that this substantial nationalist support is largely manufactured by the pro-union bias in the measure of long-term constitutional preference (Burke, 2021). Before I take up this matter below, I wish to say a little more about another important trend evident in the data.

Figure 3 indicates a stunning collapse of nationalist support for the union from 2013-2014. For nationalist identifiers, support for the union falls from its peak of 45.7 percent in 2013 to just 12.9 percent in 2020, a decrease of almost 33 percentage points. For nationalist party voters, support for the union is more than halved, from 51.9 percent in 2014 to 22.6 percent in 2020. The year 2020 shows the lowest levels of nationalist support for the union in 15 years. We might speculate that the steep decline in support for the union over this period is related to ongoing Brexit crises, the build-up of popular mobilization campaigns calling for a united Ireland and, perhaps, Stormont’s chronic dysfunction and Westminster’s increasingly obvious disarray.[16]

As mentioned above, all the percentages after 2006 in Figure 3 probably overestimate the level of pro-union sentiment because of the biased measure of constitutional preference. Support for the union would be consistently lower — through all the post-2006 ups and downs in the figure — if an unbiased or less biased measure were in use. This realization makes the recent disintegration in nationalist support for the union all the more striking.

Figure 4 points to the impact of question bias on the level of support for the union. It repeats, for nationalist identifiers, the kind of analysis we conducted in Figure 2 for all respondents. Figure 4 compares the level of nationalist support for the union using a biased and unbiased (less biased) measure of constitutional preference. In each of the three years in which both measures are available, the biased measure on the black line shows much higher levels of support for the union than does the unbiased measure on the grey line. In 2019 and 2020, the grey line indicates that support for the union among nationalist identifiers has all but evaporated, decreasing to single digits.

To recapitulate, the last two figures examine directly the adjusted forms of Proposals 2 and 3. Proposal 2 demands majority nationalist consent for union, Proposal 3 significant nationalist support of at least 40 percent. Three major conclusions emerge from the analysis of NILT surveys: (1) there is neither majority nationalist consent nor significant nationalist support for union in the first nine years of the Agreement; (2) the required levels of nationalist support are reached occasionally, but only after the survey begins using a biased measure of constitutional preference that overestimates support for the union; and (3) nationalist support for the union plummets in the last 8 to 10 years, well below the thresholds set by Proposals 2 and 3.

Proposals 2 and 3 fail the reciprocal test even more miserably than does Proposal 1. Since there is no nationalist consent for union, there is correspondingly no democratic or egalitarian justification for the proposals to require unionist consent for unity. If the union can persist without nationalist consent, why must Irish unity await unionist consent?

No matter how we define the communities—as nationalist, Catholic or Irish—Proposals 2 and 3 still fail the reciprocal test.

Conclusion: The Ethos of Partition

That northern nationalists do not consent to partition is hardly a new finding. The absence of consent dates from 1921, not from 1998 when my study begins.[18] Generally, the purpose of my analysis is to track empirically the state of public opinion on support for the union since the signing of the Agreement. In particular, it is to use survey data on constitutional preference to assess the political implications of three major proposals to alter the GFA’s simple majority rule for constitutional change.

The essence of the three proposals is to insert a unionist veto over constitutional change. The proposals lack reciprocity in that they fail to provide for an equivalent nationalist veto over maintaining current constitutional arrangements. Their direct and intended effect is to delay or stifle Irish unity without disturbing the union.[19] In fact, the hulking form of the constitutional status quo unmasks a fatal flaw in the proposals’ attempts to alter the rules for establishing a united Ireland.

The data analysis demonstrates that each of the proposals fails the reciprocal test on the constitutional status quo. The data showing that there is no supermajority for union reveal the hollowness of Proposal 1’s demand that there must be a supermajority for unity. The analysis demonstrating that there is no nationalist consent for union uncovers the hypocrisy of Proposal 2’s and Proposal 3’s requirement of unionist consent for unity.

The proposals treat the two constitutional communities unequally and unfairly, privileging unionists and subordinating nationalists. They withhold from nationalists the very rights and powers over constitutional status that they grant to unionists. The proposals place added value on unionist votes while they discount the value of nationalist votes.

These superior-subordinate relations — part of the very structure of the three proposals — are reminiscent of the ethos of partition. Every supporter of the proposals is in effect telling northern nationalists, as the architects of partition told them in 1921, to accept their inferior rank on the constitutional question. The proposals can succeed in their aim of quashing Irish unity only by further normalizing and extending the communal injustice inherent in partition.

Nationalists and republicans might consider posing some tough questions to commentators who continue blithely to peddle the glaring inequality in the three proposals. One question is: why should nationalists be expected to continue living with the same set of constitutional circumstances that unionists should not even have to contemplate?

Notes

[1] I’ve explored these proposals in a different context in Burke (2017 & 2020).

[2] In the 1998 NILT survey, Protestants and Catholics made up 90.8 of the sample; in 2020, they made up only 72 percent. Over the years of the survey, the “no religion” group has tripled in size, from 9.3 percent in 1998 to 28 percent in 2020. These figures are taken from the RELIGCAT variable.

[3] In the years before the Agreement, there were numerous calls to establish unionist majority consent as a precondition of Irish unity (Crick, 1986; Cadogan Group, 1992; Opsahl Inquiry, 1993; Guelke, 1997). These calls can be seen as direct precursors of Mallon’s position.

[4] I’m quoting from the Kindle edition of Mallon’s book A Shared Home Place, which uses location numbers instead of page numbers. Hereafter, I’ll use the abbreviations “loc.” and “locs.”

[5] See Burke (2020) for a detailed critique of Mallon’s proposal.

[6] Ahern’s views here on a supermajority and dual community consent are notably different from his position in 2003, when he praised the constitutional provisions of the GFA: “For the first time, a precise mechanism for achieving a united Ireland, which is possible only with the consent of the Irish people, has been defined and accepted by all sides” (Ahern, 2003, p. 28). Ahern is now suggesting that, in practice, the Agreement’s vaunted “precise mechanism” should be ignored.

[7] The quotation is from Pollak (2017). Pollak’s advocacy of significant or substantial unionist support for Irish reunification has recently evolved. In 2019, he articulates his position in the context of Mallon’s notion of parallel consent (Pollak, 2019). In 2021, he suggests that parallel consent is not a plausible threshold because a majority of unionists will never support Irish unity. He instead requires support from “a significant minority of unionists” as measured by a supermajority in a border poll (Pollak, 2021, p. 12).

[8] Others have pointed to this difficulty (Democratic Dialogue, 1997; SDLP 2020; O’Leary 2021). Mallon acknowledges that the communal registration of voters poses a challenge to his proposal for parallel consent to constitutional change; but he does not squarely face the matter (Mallon, 2019, loc. 4092).

[9] O’Leary applies the reasoning of the reciprocal test to the supermajority threshold (Proposal 1): “A change to require a qualified majority [supermajority] vote for the north to reunify with Ireland should logically require that a qualified majority vote be required to sustain the status quo” (O’Leary, 2021, p. 9). Humphreys applies such reasoning in examining the case for unionist consent to constitutional change (Proposals 2 and 3): “... the really fundamental reason ... why a minority or a dual consent requirement could never act to prevent the reunification of the island of Ireland if a majority so wished, is that there is no corresponding provision at present permitting the nationalist and republican ‘minority’ to prevent Northern Ireland from remaining part of the United Kingdom” (Humphreys, 2009, p. xxi). That is, both authors employ the same logic that I use in adjusting the three proposals.

[10] These figures refer to valid votes in Westminster elections and to first preference votes in Assembly, local and European elections.

[11] The 1998 percentages do not sum exactly to 100 percent because of rounding error. In some surveys after 2006, there are a small number of respondents who do not answer or refuse to answer the question on long-term constitutional preference. The NILT datasets define these responses as “missing data” and they are not included in the calculation of percentages in the figures. There are so few respondents in this category, averaging only 8 people (0.7%) across the relevant NILT samples, that their exclusion from the analysis does not materially alter the percentages shown in the figures or the substance of the conclusions drawn from those figures.

[12] For those familiar with the NILT data or who might examine the data tables published on the NILT website, the change of question in 2007 is associated with a change in the name of the variable. NIRELAND is the name of the variable measuring long-term constitutional preference from 1998 to 2006. The new variable NIRELND2 appears in 2007 to reflect the new response options.

[13] The names of the “vote tomorrow” variables in Figure 2 are BORDPOLL (2017) and REFUNIFY (2019 and 2020). BORDPOLL is based on the question: “If there was a referendum tomorrow about whether Northern Ireland should leave the UK and unite with the Republic of Ireland, how do you think you would vote? I would vote for Northern Ireland to remain part of the UK; I would vote for Northern Ireland to unite with the Republic of Ireland; I wouldn’t vote; I don’t know.” REFUNIFY is from the question: “Suppose there was a referendum tomorrow on the future of Northern Ireland and you were

being asked to vote on whether Northern Ireland should unify with the Republic of Ireland. Would you vote ‘yes’ to unify with the Republic or ‘no’? Yes, should unify with the Republic; No, should not unify with the Republic.”

[14] Survey researchers need to be aware of the validity and reliability of their measures. Figure 3 uses standard measures of nationalism whose validity and reliability should not be a problem.