Neither does the government seem to have gained any expected bounce from the easing of Covid restrictions.

Not that the issues raised by the appointment of Zappone, and the light it shone into how nice people get along thanks to other nice people, are not important. Most people, however, probably consider that all parties – including the one they support – will do the same.

It was noticeable, too, that none of the opposition parties questioned the fact that the state ought to create a separate LGBT+ envoy as distinct from a human rights representative. When this issue was raised by Senator Sharon Keogan she was rounded upon from all sides with a virulence which said all you really need to know about the left liberal consensus that dominates political life and opinion in this state.

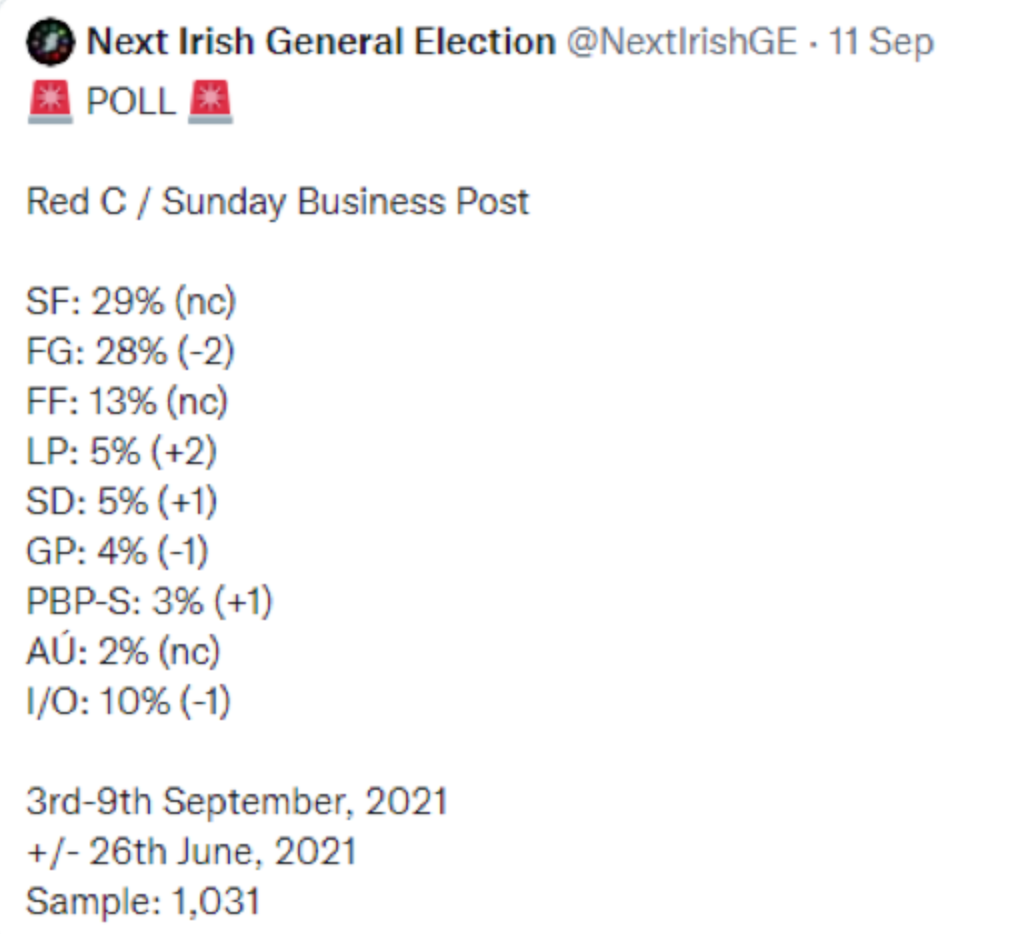

Sinn Féin, the party now sitting on top of the compost heap according to recent polls, have responded to the “crisis” with yet another in a series of no confidence motions. This one is directed at Minister for Foreign Affairs Simon Coveney who found himself in the hot seat once the earlier furore of who had been in the Merrion Hotel was replaced by the furore over the texts.

The motion of no confidence will be taken on Wednesday when the Dáil resumes. It is a tired old parliamentary routine that is often deployed to kick start a new season and give the impression that something exciting is going on. It does have the added ingredient that Taoiseach Micheál Martin can be attacked over his application of the party whip to all Fianna Fáil TDs to ensure that they support the Government.

Sinn Féin have attempted to make capital of Martin, who did lose face over the manner in which the appointment was handled, ordering his TDs to perhaps vote against their true inclinations. Something the Shinners know all about, of course, when they refused to allow their elected representatives to vote according to their conscience on abortion.

All the circus stuff aside, one cannot help but notice that Leo and the other Fine Gael ministers have embraced the no confidence challenge with gusto. Varadkar and others have hit back at Sinn Féin with counter claims of their own, with the clear intent to continue to frame the battle for political power in the state as a Manichean choice between themselves and Mary Lou McDonald’s party.

Which suits both of them, let’s be honest about it. For all that Fine Gael and Sinn Féin occupy basically the same ideological centre left space – a tax rate here and a thousand promised social houses there aside – the polls indicate that the next general election will indeed most likely come down to a choice between a coalition led by one or other of those parties.

Which leaves Fianna Fáil in the invidious position that they will be dependent on the favour of one of the two big parties if they are going to be part of another coalition. It is humiliating of course, but they seem to have gotten well beyond that by this stage. That explains their desperation to maintain the coalition in power, and their best hope is that Fine Gael and themselves with the Greens or other add-ons get more seats than an alternative coalition led by Sinn Féin.

Sinn Féin pay lip service to the concept of a “left government”, but it is unlikely that the smaller left liberal and far left parties will win enough seats to deliver that. Even the defection by the Greens would not be sufficient as things stand to elect McDonald Taoiseach. So Sinn Féin will most likely also need Fianna Fáil and/or independents who don’t lean left.

It is of course possible – and certainly the polls (with FF down 9% on the 2020 general election) are ominous for Micheál Martin’s leadership – that the Fianna Fáil vote will be further cannibalised. Indeed, this is already evident in the fact that both Fine Gael (+7) and Sinn Féin (+4.5) have feasted on the seemingly terminal descent into the margins of Fianna Fáil.

Sinn Féin’s concern has to be that the collapse in the FF vote and the sharp decline in support for the Greens is not mainly rebounding to their benefit. The Dublin Bay South bye-election was an indication that there are a substantial number of voters who whatever their antipathy to the government, and above all to Fianna Fáil, will always choose the ABTS (Anybody But The Shinners.)

Not that this will cause them too lose too much sleep. If the successful riding of the straining horses of working-class protest, bourgeois liberalism and conformism can place Sinn Féin in pole position to form the next government, then they won’t care. Nor ought they, because the nature of politics is that the biggest party will always find smaller ones to reconsider their moral objections and do the business. You could almost print that on a Fianna Fáil poster at this stage.

So, it does not require much insight to realise that the order of battle as it stands is perfect for both Fine Gael and Sinn Féin. The rest of them are part of the supporting cast. Crucially, and despite the two parties sharing the same basic liberal consensus on a raft of issues, they are fishing from mostly radically different demographic electoral ponds.

Very few of those voters who identify as Fine Gael or Sinn Féin are likely to switch sides. There are a whole range of cultural and demographic factors why this is so. That was also the case when Fine Gael and Fianna Fáil dominated the political landscape. The Civil War did of course play a part in determining older party loyalties, but between the 1930s and 1980s a much greater predictor of voting allegiance was social class.

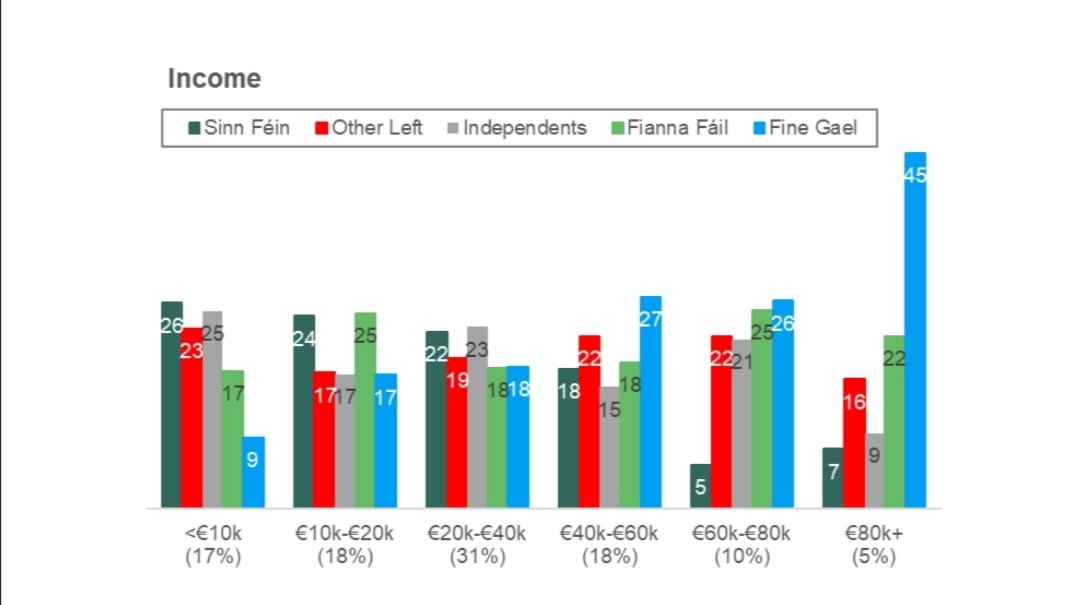

Statistician Kevin Cunningham has focused on some interesting polling data that illustrate where Sinn Féin’s appeal lies, and what differentiates them from other parties, and in particular from Fine Gael. That is particularly evident in how supporters of both parties view their economic status. Sinn Féin appeal most to those dissatisfied with their financial position – almost inversely mirroring the attitudes of most Fine Gael voters.

|

| Credit: Kevin Cunningham via Twitter |

Hence, not surprisingly, Sinn Féin voters are found predominantly among lower income groups, who favour policies that support greater income redistribution. A replication of that demographic pattern appears not only to be the basis for the electoral polarisation between Fine Gael and Sinn Féin, but one that both parties are assiduous in cultivating.

|

| Credit: Kevin Cunningham via Twitter |

Interestingly, however, Sinn Féin voters tend not to be as supportive of mass immigration and are certainly not in line with the public utterings of the party leadership and elected representatives.

|

| Credit: Kevin Cunningham via Twitter |

As Sinn Féin’s long period in government in the north proves, they are far from being the radical republican “Marxist” bogey that others including some of their own dimmer members might imagine. Their economic policies are standard opposition platforms for middle of the road social democratic parties in any country.

However, it is perception that matters most in the arena of contemporary consensus politics. Irish parties are contesting a pretty narrow and agreed ground and unlike most other European countries there is no plausible alternative outside of that. The polling stats prove that Sinn Féin are playing a shrewd game, and that Fine Gael is equally as shrewd in accepting the new paradigm which they hope will continue to place them as the most likely party of government.

No comments