A global carbon budget is the total amount of carbon dioxide emissions that human activities across the world can be allowed to generate, in order to avoid excessive global warming.

Budgets vary, according to the degrees of temperature increase that are judged to be allowable, and according to how sensitive the climate is judged to be in response to carbon emissions: the greater the sensitivity, the smaller the budget has to be.

|

| School students’ climate protest, 2019 |

The IPCC Special Report on Global Warming of 1.5 degrees provided a range of figures for the remaining global carbon budget in 2018 (Table 2.2 on page 108).

On the basis of the median climate sensitivity, the budget to limit warming to 1.5°C above pre-industrial levels was stated as 580 billion tonnes of carbon dioxide (580 GtCO2). That means the world has a mere 50:50 chance of staying below 1.5°C.

Arguably, however, a higher level of climate sensitivity is required, to give the world at least a 66% chance of reaching the 1.5°C target. At this level, the carbon budget in 2018 was 420 GtCO2.

All economic and other human activity in the world currently emits approximately 40 GtCO2 per year, so the remaining budget today in 2021 is closer to 300 GtCO2. At this rate the budget would be fully spent before 2029.

The task here is then to calculate what might count as a fair share of this budget to be allocated to the UK.

The first problem is that the global budget is for carbon dioxide only: other greenhouse gases (GHGs) such as methane and nitrous oxide are calculated separately.

Methane has minimal long-term effect on the climate, but it is a powerful greenhouse gas in the short-term, which needs to be reduced to zero as soon as possible in order to minimise its contribution to peak warming (see CCC Sixth Carbon Budget report, page 372). Arguably, therefore, a fair carbon budget for the UK should take account of all GHGs.

The CCC appear to agree, as they state: “UK carbon budgets are set on an aggregated all-GHG emissions basis and not using CO2 (or long-lived GHG) emissions alone” (page 371).

Emissions are published separately for the different GHGs in annual reports by the Department of Business, Energy and Industrial Strategy (BEIS). These are measured in tonnes of carbon dioxide on its own (tCO2) or in tonnes of carbon dioxide equivalent (tCO2e) to include all GHGs.

In calculating a fair budget for the UK, a number of factors have to be taken into account:

- GHG emissions produced within the UK, i.e. so-called production or territorial emissions, amounting in 2018 to 451 MtCO2e for all GHGs of which 366 Mt were for CO2 alone. These are the emissions counted in the BEIS annual reports, following the example of the IPCC.

- GHG emissions produced outside the UK, for which the UK has some responsibility, e.g. as consumers or exporters. These emissions are produced either through the manufacture and transport of goods that are imported to the UK, or from goods that have been produced within the UK but exported and consumed outside the UK. In 2017 imported emissions added about half as much again to the UK’s emissions total (Sixth Carbon Budget report, page 344), but the figure for exported emissions is unknown. It is important to note that this is essentially a shared responsibility between the UK and the countries with which it trades. The CCC argues that the UK should reduce what it calls its “overseas consumption footprint” by about 90% below 1990 levels by 2050.

- The UK’s historical contribution to CO2 emissions. This has been estimated at 55 GtCO2 from 1900 to 2004, which is of course considerable. However, because CO2 can stay in the atmosphere for centuries, emissions from many years ago still cause global heating. This strengthens the argument not only for reducing the UK’s overseas consumption footprint, but also for setting a much tighter budget for its territorial emissions. It is debatable from what point countries should have responsibility for their emissions, but the CCC argues that 1990 is a reasonable start date on the grounds that this is when the world became aware that such emissions are causing global warming.

- The UK’s capabilities compared to other countries. There is no general agreement on how such capabilities are to be measured, but the most common measure is in terms of Gross Domestic Product (GDP). Currently, global GDP is $92 trillion and UK GDP is $2.8 trillion. The UK has the sixth largest economy in the world and therefore has much greater capabilities than most other countries, which again implies that a tighter budget is appropriate or, alternatively, much greater assistance to other countries is required in order to reduce global emissions.

- The potential contribution that the UK can make to the reduction of emissions by the removal of CO2 from the atmosphere over and above natural carbon cycles (where carbon is regularly absorbed by oceans, soils and plants, and released later on). Basically, this can be done by natural means (such as restoring peatland, planting trees, and improving soils) or artificially, by so-called negative emissions technologies (NETs). The extent of this potential is unknown.

The next logical step would be to agree on how the global budget should be allocated to individual countries, taking account of the above factors. Unfortunately, however, no such agreement exists.

Under the Paris Agreement, signatories agree to have the “highest possible ambition”, and it is left up to the countries concerned how that is to be interpreted.

The key question here is: how far can this ambition be specified in terms of a carbon budget?

Since 2019 the UK government has been committed to reaching net zero GHGs by 2050 and this is argued to be sufficiently ambitious.

For example, in its Sixth Carbon Budget report (page 320), the CCC states that 2050 was chosen, rather than the IPCC’s global date of 2070, in order to show the UK’s greater responsibility “as a relatively rich country with a high historical contribution to climate change and high overseas consumption emissions footprint”.

Job done, you might think – until it is pointed out that the CCC’s argument is based on the assumption of a 50%, rather than 66%, chance of limiting global warming to 1.5°C, an assumption that results in a budget of 580 GtCO2, rather than 420 GtCO2.

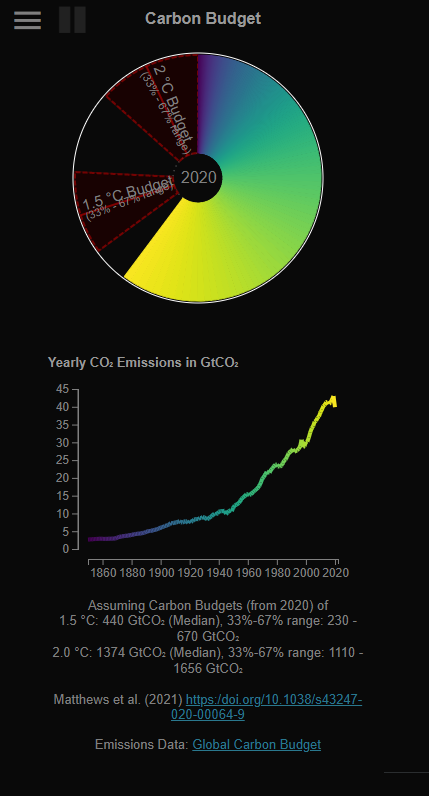

|

| The global carbon budget as a disk: what remains is in black. A screenshot from a graphic by Global Carbon Budget / Open Climate Data |

This is reflected in the CCC’s calculation that, according to their balanced net zero scenario, a budget of 580 GtCO2 from 2018 will require the world to reach net zero in 30 years, while 420 GtCO2 will mean that net zero has to be achieved in 20 years (that is, by 2038).

There are further problems with the CCC’s budget setting and with its whole “net zero in x years” approach (which, incidentally, has been consistently legally ratified by Parliament and accepted by government).

One problem is that the remaining carbon budget set for the UK from 2018, estimated by researchers at 9 GtCO2, is far too loose.

In terms of population size alone, one would expect the budget to amount to around 0.88% of the global budget (with UK population being 67 million and global population 7,900 million); for a global budget of 580 GtCO2, this results in a UK budget of 5 GtCO2, significantly lower than 9 GtCO2.

(For the sake of argument: if the UK were to adopt an arguably Paris-compliant target in line with a 50% chance of 1.7°C instead of 1.5°C, the global budget would be 900 GtCO2, meaning a UK budget of 8 GtCO2, which would still be below the budget implied by the CCC’s approach).

So, even on the most generous of interpretations, the UK’s budget is larger than it should be.

The CCC’s budget is compliant with the Paris Agreement only at the level of a 50% chance of 2°C of warming – and then only if we accept their political assumptions about the UK’s share of the budget, and the way that it ignores the UK’s historical emissions legacy and its current capabilities.

Those capabilities can be measured in different ways. As a crude measure, however, I suggest using the UK’s comparatively high GDP. This amounts to 3% of global GDP, which is more than three times the global average given the relative size of the UK’s population, from which it follows that the UK should contribute three times as much to reducing emissions as the global average.

The CCC is concerned only to ensure that its proposed pathway to net zero is cost effective, not detrimental to competitiveness, attentive to fuel poverty, fiscally balanced, takes sufficient account of devolved administrations, and so on. It regards UK capabilities for mitigating climate change as limited to spending an equivalent of 1-2% of its GDP.

As for addressing the UK’s “high historical contribution to climate change”, the CCC recommends only climate financing for developing countries, particularly for low-carbon technology (see Sixth Carbon Budget report, pages 320 and 323).

It is important to note that the CCC’s balanced net zero (BNZ) pathway represents the minimum ambition to reach net zero by 2050, and I have criticised this lack of ambition – or rather lack of the right kind of ambition – in the linked article. They do present (page 87) a more ambitious alternative pathway – the Tailwinds scenario – which gets to net zero in 2042, but this assumes massive application of carbon capture and storage and is much more expensive than the BNZ pathway.

(Interestingly, a Tailwinds scenario with minimal carbon capture and storage (CCS) “was not costed or explored, and so is not a recommended pathway” (page 90); it would reach net zero by 2042 instead of 2050.)

Perhaps more importantly, the CCC itself shows that its BNZ pathway is inferior to what would be required for 1.5°C on the basis of a number of equity principles, in particular to be consistent with a global target of individual purchasing power of $20 a day. (See the Climate Equity Reference Calculator and the Sixth Carbon Budget report, page 324, Figure B7.2).

Moreover, the pathway assumes substantial application of carbon capture and storage technologies after 2030, which are required because the budgets before that are too generous; if the earlier budgets were much tighter, then the reliance on CCS would be correspondingly reduced.

This is an example of what I mean by the wrong kind of ambition.

At the same time, of course, this would mean that the budgets would already be spent. Planting billions of trees would certainly help, but trees take time to grow, and time is running out. The powers that be still do not seem to understand this.

All of this discussion so far is based on the UK’s assumption of only a 50% chance of hitting the global target of 1.5°C.

At current levels of emissions, this global budget will be overspent by 2029, so a global temperature rise of 1.5°C is as likely as not to be made inevitable by then.

However, this does not justify the UK continuing with its current much looser budget. On the contrary, it means that the UK must adopt a tighter budget in order to mitigate the damage that this overheating may cause across the world.

More importantly, it means that the UK must take more urgent and drastic action to ensure that it does not itself contribute to this overheating.

There are further problems with the CCC’s budget setting and with its whole “net zero in x years” approach (which, incidentally, has been consistently legally ratified by Parliament and accepted by government).

One problem is that the remaining carbon budget set for the UK from 2018, estimated by researchers at 9 GtCO2, is far too loose.

In terms of population size alone, one would expect the budget to amount to around 0.88% of the global budget (with UK population being 67 million and global population 7,900 million); for a global budget of 580 GtCO2, this results in a UK budget of 5 GtCO2, significantly lower than 9 GtCO2.

(For the sake of argument: if the UK were to adopt an arguably Paris-compliant target in line with a 50% chance of 1.7°C instead of 1.5°C, the global budget would be 900 GtCO2, meaning a UK budget of 8 GtCO2, which would still be below the budget implied by the CCC’s approach).

So, even on the most generous of interpretations, the UK’s budget is larger than it should be.

The CCC’s budget is compliant with the Paris Agreement only at the level of a 50% chance of 2°C of warming – and then only if we accept their political assumptions about the UK’s share of the budget, and the way that it ignores the UK’s historical emissions legacy and its current capabilities.

Those capabilities can be measured in different ways. As a crude measure, however, I suggest using the UK’s comparatively high GDP. This amounts to 3% of global GDP, which is more than three times the global average given the relative size of the UK’s population, from which it follows that the UK should contribute three times as much to reducing emissions as the global average.

The CCC is concerned only to ensure that its proposed pathway to net zero is cost effective, not detrimental to competitiveness, attentive to fuel poverty, fiscally balanced, takes sufficient account of devolved administrations, and so on. It regards UK capabilities for mitigating climate change as limited to spending an equivalent of 1-2% of its GDP.

As for addressing the UK’s “high historical contribution to climate change”, the CCC recommends only climate financing for developing countries, particularly for low-carbon technology (see Sixth Carbon Budget report, pages 320 and 323).

It is important to note that the CCC’s balanced net zero (BNZ) pathway represents the minimum ambition to reach net zero by 2050, and I have criticised this lack of ambition – or rather lack of the right kind of ambition – in the linked article. They do present (page 87) a more ambitious alternative pathway – the Tailwinds scenario – which gets to net zero in 2042, but this assumes massive application of carbon capture and storage and is much more expensive than the BNZ pathway.

(Interestingly, a Tailwinds scenario with minimal carbon capture and storage (CCS) “was not costed or explored, and so is not a recommended pathway” (page 90); it would reach net zero by 2042 instead of 2050.)

Perhaps more importantly, the CCC itself shows that its BNZ pathway is inferior to what would be required for 1.5°C on the basis of a number of equity principles, in particular to be consistent with a global target of individual purchasing power of $20 a day. (See the Climate Equity Reference Calculator and the Sixth Carbon Budget report, page 324, Figure B7.2).

Moreover, the pathway assumes substantial application of carbon capture and storage technologies after 2030, which are required because the budgets before that are too generous; if the earlier budgets were much tighter, then the reliance on CCS would be correspondingly reduced.

This is an example of what I mean by the wrong kind of ambition.

At the same time, of course, this would mean that the budgets would already be spent. Planting billions of trees would certainly help, but trees take time to grow, and time is running out. The powers that be still do not seem to understand this.

All of this discussion so far is based on the UK’s assumption of only a 50% chance of hitting the global target of 1.5°C.

At current levels of emissions, this global budget will be overspent by 2029, so a global temperature rise of 1.5°C is as likely as not to be made inevitable by then.

However, this does not justify the UK continuing with its current much looser budget. On the contrary, it means that the UK must adopt a tighter budget in order to mitigate the damage that this overheating may cause across the world.

More importantly, it means that the UK must take more urgent and drastic action to ensure that it does not itself contribute to this overheating.

|

| This graph is by Glen Peters, a climate researcher. It compares CO2 emissions along a global pathway to “net zero” in 2050 (green), a pathway reflecting the promises made by governments (yellow), and a pathway reflecting current government policies (blue) |

Based on relative population size alone, a global budget of 420 GtCO2 translates into a UK budget of 3.7 GtCO2, so this represents an upper limit for a fair UK carbon budget.

At current levels of CO2 emissions alone (366 Mt in 2018), such a budget would be spent by 2028. Interestingly, this is consistent with the global position set out in the IPCC’s 2018 Special Report on 1.5°.

But it is still a long way from representing the highest possible ambition, since it takes no account of factors 2, 3 and 4 above. Taking account of these factors would likely result in a budget of less than zero.

Even so, a 3.7 GtCO2 budget would be a huge advance in comparison with the current UK budget, and would require radical changes in government policy and intervention.

Taking account of all relevant factors, then, effectively drives a coach and horses through the carbon budgeting process.

Does this matter? We know the main sources of emissions in the UK, we need to reduce those emissions as quickly as possible, and we need clear action plans that will do just that. When one is in an emergency situation, is it really worthwhile spending much time working out how long we have left to address the emergency?

The uncomfortable truth is that the budgeting approach to emissions reduction has tended to delay action rather than speed it up – perhaps most notably in the “over-performing” of some of the CCC’s five-yearly budgets.

With the right kind of ambition, therefore, the UK can make a fair contribution to limiting global warming to 1.5°C.

Download these articles on carbon budgets, as a pdf

■ This is the second of two linked articles. The first one, about the CCC and the Sixth Carbon Budget, is here.

⏭ Keep up with People And Nature. Follow People & Nature on twitter or instagram or telegram or whatsapp. Or email peoplenature@yahoo.com, and you will be sent updates.

No comments