While never callous or triumphalist, Magee remains adamant that his participation in the IRA’s armed campaign was justified and indeed necessary. Consequently, he gives us an insight into the mind and world view not just of the thousands of young men and women who participated in that underground organisation but of the communities that supported them.

With an insider’s understanding, he tells of the feeling of abandonment after partition and of the systemic discrimination practised against a community in order to maintain a “Protestant state for a Protestant people,” a situation that resulted in the ever-present threat of state-endorsed violence in order to sustain that undemocratic regime.

In spite of the fact that he spent many of his formative years living with his parents and siblings in England, Magee always thought of himself as a Belfast person — not only that but a particular type of Belfast person: a Catholic from the Markets district of the city, a district with a distinct culture and a troubled history, one of several small nationalist enclaves that had for decades been subject to sporadic attack, causing a pervasive apprehension among its inhabitants.

As the historian Eamon Phoenix told the BBC in a podcast about the violence surrounding the foundation of Northern Ireland in 1921, Belfast was the “fulcrum” of much of the bloodshed.¹ More than 450 people were killed in the conflict between June 1920 and July 1922. Nearly 60 per cent were Catholic, and the overwhelming majority were civilians. Nor did violence end in the 1920s. Even in the relatively peaceful early 1960s rioting broke out near the Market when, in June 1964, Ian Paisley led a group of loyalist hardliners to the edge of the district.

A feature of recurring violence was the role of the state’s forces. At best neutral when nationalist areas were under attack, they were on many occasions party to the assaults. The decidedly British establishment figure Max Hastings recently wrote how in 1969 he witnessed “Protestant police hosing down a Catholic block of flats in Belfast with a heavy machine-gun, killing a nine year-old boy.”²

Because of Northern Ireland’s violent history, the IRA was viewed in many working-class Catholic areas of Belfast at least as much as their last line of defence as the armed champions of an all-Ireland republic. That much is evident as Magee writes about his grandparents and their contemporaries, several of whom were members of the IRA in the 1920s and imprisoned for their part in the organisation.

Not surprising, therefore, that with this folk memory, coupled with what he witnessed in the early 1970s, the young Magee would join the republican movement. Living not in the Markets but in the nearby and equally vulnerable Unity Flats complex, he was to recount, among much else, the trauma of seeing lethal loyalist attacks on residents of the district, the brutality of the British army, and its shooting dead of his friend Louis Scullion.

Whatever others may consider the broader context for these occurrences, the author provides his readers with an accurate insight into what was a widely held view among his contemporaries in working-class nationalist areas of Belfast and elsewhere in the North—a viewpoint that goes a long way to explain the degree of community support enjoyed by the IRA, described here by Magee as he writes of open doors, children acting as lookouts, and middle-aged women storing weapons. It was from within these communities and their experiences that the Sinn Féin electoral machine was later to develop.

This too was the maelstrom that caused Magee to emerge from internment (and intensive police harassment thereafter) with his commitment to the republican struggle unchanged, a commitment that brought him, as the IRA would have seen it, to “take the war to Britain” and eventually to the Grand Hotel in Brighton, leading him to a famous trial and years of imprisonment.

Had the Magee story ended there he might well have eventually faded into the background, as others have done, a name to be searched for occasionally by journalists looking for a story. That this didn’t happen is in no small measure due to his extraordinary meeting, and work thereafter, with Joanna Berry, the daughter of one of those killed in the Grand Hotel.

In a remarkable act of generosity, Berry sought not to excoriate but to understand what motivated those behind the bombing. Moreover, she persisted in doing so while Patrick Magee, notwithstanding his expression of remorse for her personal loss, remained, and remains, adamant that his cause and actions were justified. Together they sought to build bridges between the different protagonists in an effort to promote reconciliation. To do so they travelled extensively, speaking to audiences around the world. One such trip offered a rare insight into the extensive reach of US imperialism when, despite extensive efforts, the US government prevented Magee speaking at a public meeting in Mexico.

However well-meaning they were, and remain, their best efforts have met with little success. The mainstream media in Britain and Ireland constantly focus on their unusual relationship, casting it as a “perpetrator meets victim” sensation rather than hearing their message of the need for real understanding and respect.

To a large extent the media are merely reflecting the views and interests of the British establishment, and in particular that of the British state. It was, after all, the powers that be in London that were instrumental in the creation of Northern Ireland in 1921. It was London that turned a blind eye to Stormont’s anti-democratic practices for the following fifty years, and London that thereafter conducted a colonial-style thirty-year military campaign to contain the inevitable resistance to its misrule.

It would not profit the British state to acknowledge misgovernment on such a scale. To correct the narrative would involve revealing an appalling vista of contempt, duplicity, intrigue and the sponsoring of lethal “dirty operations” over decades, the consequences of which would further harm its image globally and also undermine its determination to influence Irish affairs into the future.

In spite of this caveat, Patrick Magee has made a valuable contribution to our understanding of a conflict that raged for almost three decades in the North of Ireland. There is, nevertheless, another story to be told of the period that will reflect what Bertolt Brecht said to those who follow in our wake:

Even anger against injustice

Makes the voice grow hoarse. We

Who wished to lay the foundation for gentleness

Could not ourselves be gentle

“To Those Who Follow in Our Wake” (1939)

References

¹ Catherine Morrison, “NI 100: How Northern Ireland’s birth was marked by violence,” BBC News NI, 11 February 2021 (https://www.bbc.com/news/uk-northern-ireland-56018758)

² Max Hastings, “There will always be an England, but not a UK,” Bloomberg Opinion, 14 February 2021 (https://bloom.bg/2OWyCGq)

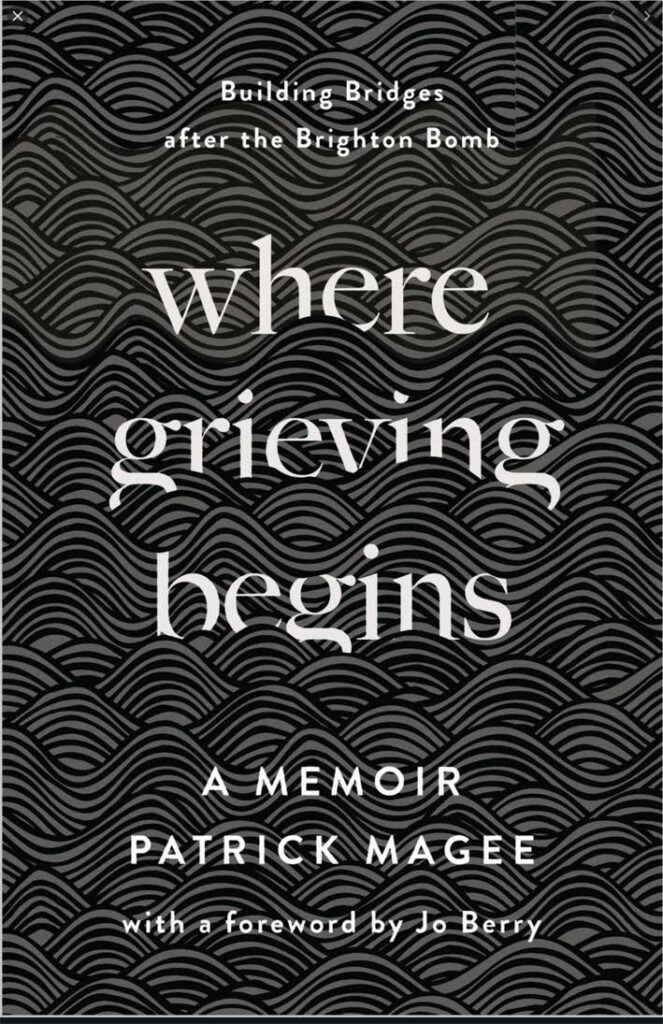

Patrick Magee, 2021, Where Grieving Begins: Building Bridges after the Brighton Bomb. London: Pluto Press.

|

Tommy McKearney is a left wing and trade union activist. He is author of The Provisional IRA: From Insurrection to Parliament. Follow on Twitter @Tommymckearney |

After yesterday's ruling in the Ballymurphy Massacre inquest, the context of the time as described by Pat Magee is firmed up even further. The British are a long way off from acknowledging their state terrorism in Ireland and the role it played in driving the youth into armed insurrection.

ReplyDelete