Gabriel Levy in the first of a three part series examines the work of Rupert Read on Disaster Environmentalism.

|

The international climate negotiations in Katowice, Poland, in 2018, which were supposed to follow up on the Paris agreements, “can be seen as achieving no more than an elaborate seating-plan for the sun-deck of the Titanic”.

In 2020, countries are supposed to show how they have met the targets set at Paris, and set tougher targets. “But even if a radical programme of reduced emissions was started at that point, and one that went far beyond the Paris Agreement, it would need to achieve zero emissions by 2040 to stay within the 2 degrees C limit. […]

|

|

One demonstration: two approaches.

From the school students’ protest, 29 November, 2019

|

Surely the most optimistic assumption we are entitled to make, based on current political agreements and actions across the world is that emissions will continue to rise after 2030, hopefully levelling off later in the century.

And so “we must assume” that there will be “a global temperature rise associated with carrying on as we are”: that means, by 2100, “at the very least” 3-4 degrees C, and “more likely” 4-5 degrees C.[1]

I agree with all that – with the caveat that those temperatures are consistent with “carrying on as we are”, whereas I believe we have the capacity to do things differently. It is from the Introduction to a new book from the Green House think tank, Facing Up to Climate Reality.[2]

The Introduction argues (i) that “dangerous climate change is now inevitable” and (ii) that “we are going to have to live in a post-growth world”.

This is the starting point of what I call disaster environmentalism, being developed by Rupert Read (one of the Introduction’s three authors), Jem Bendell and other writers associated with Extinction Rebellion (XR).

In a book, This Civilisation is Finished, Read underlines: “there is no ‘safe’ level of warming”; that limiting warming to 2 degrees C, which is now “amost unachievable”, will mean the death of 99% of the world’s coral reefs, and probably the end of ice in the northern hemisphere. It means more extreme weather events, and an increase of violence and war globally. “It is violence: 2 degrees is violence from the rich and stupid against the global masses.” I agree with that, too.

Read goes on to argue that “the climate crisis and the broader ecological emergency of which it is only the most urgent part puts the whole of what we know as civilisation at risk”. And:

By “this civilisation” I mean the hegemonic civilisation of globalised industrial growth capitalism – sometimes called “Empire” – which today governs the vast majority of human life on Earth.

He then presents three possible futures:

- 1 “This civilisation could collapse utterly and terminally, as a result of climatic instability (leading for instance to catastrophic food shortages as a probable mechanism of collapse), or possibly sooner than that, through nuclear war, pandemic, or financial collapse leading to mass civil breakdown.”

- 2. “This civilisation (we) will manage to seed a future successor-civilisation(s), as this one collapses”.

- 3 “This civilisation will somehow manage to transform itself deliberately, radically and rapidly, in an unprecedented manner, in time to avert collapse.” (On one hand, Read adds in a footnote that it is “just about conceivable that this civilisation might survive by adopting an extremely disciplined eco-fascism”, although “such a way of life […] should not properly be regarded as civilised”; on the other hand, elsewhere he says that transforming civilisation would be “the most desirable” option, but “by far the least likely”.)

Disaster environmentalism could be characterised as a trend that deliberately distances itself from the idea that fighting to transform society is necessary and possible.

Read himself counterposes his own view to “virtually everyone in the broader environmental movement” who is “fixated on the third option”. In this, he sees himself in agreement with Bendell; John Foster, co-chair of Green House; Jonathan Gosling, a professor of leadership, and the “Dark Mountain” literary collective.[3]

Read, Foster and Bendell wrote a joint open letter to David Wallace-Wells, author of the best-selling book on climate change, The Uninhabitable Earth, arguing that – while Wallace-Wells had shown how great the danger is – by pointing towards a range of responses aimed at averting it, he was avoiding reality. They called on him to embrace “deep adaptation”, by “accepting that some kind of eco-induced societal collapse is now not merely possible, but likely, and preparing honestly for it”.

|

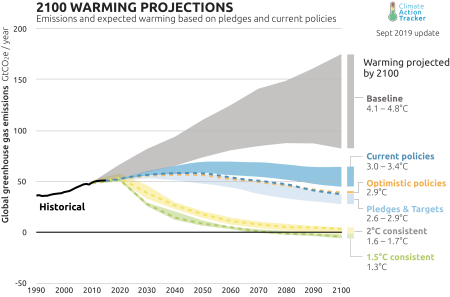

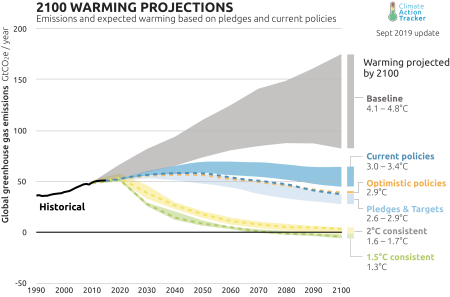

Carbon Action Tracker’s projections for global temperature, up to 2100

|

Read’s view of our possible futures does not work for me at all.

It is based on a first-world idea of “civilisation” (what, after all, makes global industrial capitalism so “civilised”? and how do we categorise those, such as indigenous peoples in the global south, who have so far managed to live mostly outside its grip?).

It conjours up a Hollywood-movie-style spectre of “social collapse”, at odds with all the fearsome evidence of social crises that we already have in hand. And it comes close to ruling out the prospect of people acting collectively to forestall the worst outcomes.

I do not agree, either, with some of the disaster environmentalists’ practical conclusions, summed up in Read’s call to “focus less on prevention/mitigation (i.e. less on a zero carbon target) and more on adaptation”.[4]

Jem Bendell is more adamant than others, in his paper on Deep Adaptation, that it is too late to forestall disaster. He has “chosen to interpret the information [about climate change] as indicating inevitable collapse, probable catastrophe and possible extinction”[5] – and from this concludes that “deep adaptation”, centred on what he calls “relinquishment” (of things we are used to having) and “restoration”, is the way forward.[6]

This borders on survivalism: “Existing approaches to living off-grid in intentional communities are useful to learn from, but this agenda needs to go further in asking questions like how small-scale production of drugs like aspirin is possible.”[7]

It also borders on much more pessimistic narratives about how the 21st century will unfold. Bendell writes:

There is a growing community of people who conclude we face inevitable human extinction and treat that view as a prerequisite for meaningful discussions about the implications for our lives right now. For instance, there are thousands of people on Facebook groups who believe human extinction is near.[8]

Bendell points out that eschatology, i.e. “reflection on the end of times”, is a major dimension of the human experience”.

This bleak view of the future is related to another aspect of disaster environmentalism which, rather than recognising the huge element of uncertainty inherent in predictions of the future by climate scientists, earth systems scientists, or anyone else, focuses only and deliberately on worst-case scenarios. A good example is the confident assertion by Roger Hallam, one of XR’s founders, of “the slaughter, death, and starvation of 6 billion people this century”.

This seems to me somehow connected with Hallam’s relativising of the Holocaust as “just another fuckery in human history”. This reactionary idiocy has quite rightly been denounced by, among others, XR Germany, XR UK and XR Jews. Good for them. Here I only add that Hallam’s distorted view of the 20th century is linked to a distorted view of the 21st. As he said when apologising for his statement:

I want to fully acknowledge the unimaginable suffering caused by the Nazi Holocaust that led to all of Europe saying ‘never again’. But it is happening again, on a far greater scale and in plain sight. The global north is pumping lethal levels of CO2 into the atmosphere and simultaneously erecting ever greater barriers to immigration, turning whole regions of the world into death zones.

It is not that climate change could cause situations in which Holocaust-like horrors are repeated, but that it is doing so, now, in Hallam’s world. There are no timescales; no doubt; little or no room to act collectively as human beings. There is only “rebellion”, on Hallam’s terms, and catastrophe. This is, in my view, a clear statement of disaster environmentalism.

This three-part article is my attempt at a response. In this first part, I will argue (1) that the disaster environmentalists are right to denounce the international climate talks, and the whole political circus that aims at normalising the causes of climate disasters; (2) that their vision of “social collapse” is deeply flawed; and (3) that, while adaptation – in the sense of facing the consequences of these disasters – is an urgent, near-term, life and death problem, it should not be counterposed to efforts to mitigation, i.e. tackling the causes of greenhouse gas emissions and climate change. In two further parts of the article, I discuss prospects for moving to a post-growth economy, and the practical activity of movements around climate change.

1. The international climate talks are a fraud

Disaster environmentalism smashes through the layers of lies and doublethink that emanate from the international climate talks and are embellished by politicians, oil companies, economists and some big NGOs. Brian Heatley, Rupert Read and John Foster write:

the stark, categorical truth is that things are now certainly going to get worse – much worse – whatever we do. Hardly anyone wants to admit this. It sometimes seems as if almost the entire world is engaged in climate denial – not just those with vested interests in minimising the dangers, but also those working passionately to save us from them.[9]

I agree that things will “certainly” get worse, because, even if greenhouse gas emissions started falling sharply from tomorrow, the effects of those gases already put into the atmosphere will take several more years to take full effect.

Are the disaster environmentalists right to denounce the discourse of illusory hopes surrounding the international climate negotiations? I think so (and said so in 2015, for example).

Another way of looking at the talks is that they have strengthened the movement to tackle dangerous climate change, and that the struggle for an international agreement on climate “has to be fought out alongside many other battles to defend the environment, including direct action”. That’s how the socialist writer Alan Thornett puts it.[10]

I am not against trying to force governments to act, as Thornett urges. But I think we also need to recognise that a central function of the talks process, ever since the Rio convention of 1992, has been to create the illusion that governments are taking care of things, when in fact they are not. To my mind, this is a planetary example of the way that the state functions in society generally: claiming, in increasingly sophisticated terms, to safeguard the common interest, while reinforcing the power and wealth of the ruling class.

Disaster environmentalism strikes a chord, because people now realise just how deceptive the international climate talks have been. The cynicism of politicians that people experience at more local levels is reproduced, with chilling effect, on the global stage. As Greta Thunberg, who initiated the school strikes, said in her speech to the UN climate summit:

How dare you pretend that this can be solved with just ‘business as usual’ and some technical solutions? With today’s emissions levels, that remaining CO2 budget will be entirely gone within less than eight and a half years. There will not be any solutions or plans presented in line with these figures here today, because these numbers are too uncomfortable. And you are still not mature enough to tell it like it is.

It is the specter of disaster, summoned up by thirty years of inaction by the world’s governments, that have provoked the school strikes. The name Extinction Rebellion, and its focus on direct action, have struck a chord missed by older, more incorporated, environmentalist organisations.

This change of mood is the context in which Rupert Read shot to prominence. His refusal in August last year to debate a climate change denier on the BBC, and to turn instead to social media in protest at mainstream media acquiescence in climate science denial, attracted popular support.

The disaster environmentalists connect the Paris paralysis with illusions of “green growth”. They argue that “further net growth, at least in countries like the UK, is neither necessary, desirable, nor possible”. I agree with this, too, but I would add that “green growth” is not a state of mind. It is an ideological construct, used to defend the wealth built out of economic activity, and the power that that wealth exerts. In other words, it is a weapon of the system.

2. A flawed view of “social collapse”

The disaster environmentalists insist that climate change will inevitably (Jem Bendell) or probably (Rupert Read and others) result in “social collapse”. Bendell writes that we are “set for disruptive and uncontrollable levels of climate change, bringing starvation, destruction, migration, disease and war”.[11]

Clearly, we are in a rich country here: “migration” is listed as an external threat, rather than as a strategy to cope with the effects of climate change. Bendell’s dystopia unfolds in classic Hollywood style:

With the power down, soon you wouldn’t have water coming out of your tap. You will depend on your neighbours for food and some warmth. You will become malnourished. You won’t know whether to stay or go. You will fear being violently killed before starving to death.

Bendell specifies that all this is coming over very short timescales:

My guess is that, within ten years from now, a social collapse of some form will have occurred in the majority of countries.[12]

Read and Kristen Steele, in an article on adaptation, have a different view. They warn that storms, drought and wildfires will intensify: “These will be disasters, possibly resulting in the deaths of millions.”[13] Disasters produce collective responses, they emphasise, citing Rebecca Solnit’s book A Paradise Built in Hell.

Solnit researched the aftermath of the New Orleans floods in 2005, the 9 September terrorist attacks in New York in 2001, and other disasters in north America.[14] She summarised her findings by saying that:

the citizens any paradise would need – the people who are brave enough, resourceful enough and generous enough – already exist. The possibility of paradise hovers on the cusp of coming into being, so much so that it takes powerful forces to keep such a paradise at bay. If paradise now arises in hell, it’s because in the suspension of the usual order and the failure of most systems, we are free to live and act in another way.[15]

In none of these situations was the danger of being “violently killed” (who by? one’s neighbours? marauding “others”?) elevated above its normal level in rich-world cities. But that danger is ever-present for people in Yemen, Syria, Afghanistan and other places where various elites – “civilised” ones included – have resorted to military means.

To roll these nightmares together in an imagined, future climate-change-induced disaster, instead of confronting the real ways they are unfolding now – and the real relationship between social crisis and climate crisis – is disarming and potentially demoralising. And it is not telling the truth.

Let’s take a real and frightful example of a social crisis in which climate change played a causal role: Syria.

In 2007-2010, eastern Syria and northern Iraq experienced severe drought: the worst ever recorded. South-eastern Turkey and western Iran were also affected. In Syria, this followed a decade of moderate to serious drought (1998-2007), and was exacerbated by over-mining of groundwater. Harvests were ruined; in 2008, Syria had to import wheat for the first time since declaring grain self-sufficiency in the mid 1990s. Families in the countryside faced economic disaster, and migration into Syria’s cities intensified.

|

| Dry conditions in Syria, 2011. Photo: Joel Bombardier/Creative Commons) |

This in-migration swelled the slums and shanty towns in Syrian cities. When the government cracked down on pro-democracy demonstrators in 2011, these were among the places that exploded in protest. This rebellion merged with the “Arab spring” that swept north Africa and the Middle East.

The outcomes were messy and uneven, and even now are not settled. In Tunisia, power changed hands peacefully. Revolution turned to repression in Egypt and Syria – the latter’s far more deadly and destructive, because of the Bashar al-Assad government’s readiness to kill and torture hundreds of thousands of its own citizens, rather than grant the basic civil rights they demanded.

In 2012-13, Assad opted to militarise his vengeful assault on the population. Russia, the Gulf States (who supported Islamist militias) and the western powers (who tolerated it all) helped. And even in these unimaginably horrible conditions – by far the worst social disaster of the 21st century – there are signs of hope. Right up to today, activists in Syria and in the Kurdish enclave in the north-east refuse the label of victimhood so often fixed to them. They point out that, even now, communities continue to organise, to challenge, to assert their right to shape their lives for the better.

Was Syria’s civil war caused by climate change? A research team led by Colin Kelley of the University of California made that claim. They convinced me that drought caused rural-to-urban migration – but there were many other links to the causal chain, and they had little to say about the social and political ones. The climate scientist Mike Hulme and international relations researcher Jan Selby argued that there was no link: other countries in the Fertile Crescent had suffered drought, but not civil war, they pointed out.

Reading all this, it seemed to me that reality was more complex. I asked Leila al-Shami, co- author of Burning Country: Syrians in Revolution and War, what she thought. She told me in an email:

Climate change and drought was indeed a factor which pushed many rural farmers off their lands and into the overcrowded slums around the cities looking for livelihood opportunities. The uprising broke out first in these affected rural areas and city slums where living standards had plummeted.

But any analysis which states that climate change was the sole factor is both reductionist and completely wrong. That is clear from any analysis of the protesters’ demands in the early days of the uprising – abolition of emergency laws, release of political prisoners etc, as well as socioeconomic justice.

Further, the crisis caused by the drought was largely man made – and due to government corruption. The UN poured in huge amounts of money to address the drought, and affected communities didn’t benefit from it. Also there was a lot of corruption regarding illegal well drilling etc.

Development issues can not be separated from civil and political rights, Leila pointed out – and quoted the Indian economist Amartya Sen, who wrote that economic insecurity often relates to lack of democratic rights and liberties:

It is not surprising that no famine has ever taken place in the history of the world in a functioning democracy – be it economically rich (as in contemporary western Europe or north America) or relatively poor (as in post independence India, or Botswana, or Zimbabwe. Famines have tended to occur in colonial territories governed by rulers from elsewhere […] or in one-party states […] or military dictatorships.[16]

So while climate change contributed to the Syrian disaster, the perpetrator of mass murder was the state. People murdered each other: not marauding bands from a Hollywood dystopia, but people armed and financed by state structures. And this is true of many of the greatest social disasters of the mid twentieth century.

As the socialist writer Jonathan Neale points out, in a comment on Bendell, in all those horrors – the Nazi genocide; the famines in Bengal, Vietnam and China; the atomic bombing of Japan; the Stalinist death camps; and the killings during the partition of India – murder was “by states, and by mass political movements”, not “small groups of savages wandering through the ruins”. He argues that, in those horrors:

Society did not disintegrate. It did not come apart. Society intensified. Power concentrated, and split, and those powers had us kill each other. It seems reasonable to assume that climate social collapse will be like that. […]

Remember this, because when the moment of runaway climate change comes for you, where you live, it will not come in the form of a few wandering hairy bikers. It will come with the tanks on the streets and the military or the fascists taking power.

Those generals will talk in deep green language. They will speak of degrowth, and the boundaries of planetary ecology. They will tell us we have consumed too much, and been too greedy, and now for the sake of Mother Earth, we must tighten our belts.

Then we will tighten our belts, and we will suffer, and they will build a new kind of gross green inequality. And in a world of ecological freefall, it will take cruelty on an unprecedented scale to keep their inequality in place.

That’s an eloquent statement of the reason why tackling dangerous climate change, and resisting ruling elites and their power structures, can not be separated.

If we are to talk about “social collapse” – to my mind a very wide, and potentially meaningless, category – surely Neale’s examples must be considered. He also refers to the long-running military conflicts in Afghanistan, Darfur and Chad as social crises in which climate change has played a role.

The disaster environmentalists have nothing much to say about these real-life crises. Read and Steele refer instead to TV series such as Survivor and The Hunger Games, and the film The Road, and discuss the mainly local, mainly rich-country disasters researched by Solnit.

Disaster environmentalists including Rupert Read and Gail Bradbrook, a spokesperson for XR, point to Collapse, the popular book by anthropologist Jared Diamond, that claims to explain the “collapse” of a series of societies from those of Easter Island and ancient Mexico to Greenland and 20th-century Rwanda.[17]

They seem unaware that Diamond’s approach has been comprehensively critiqued by other anthropologists. His critics argued, many years ago, that he stripped out detail and ignored complex realities in order to justify his theories about unsustainable practices causing societies to collapse. (I wrote about this here in 2012.)

Social crisis, and the way that climate change may cause or aggravate it, is deadly serious. We can not tell the truth about it without some serious analysis.

3. Adaptation and mitigation go together

So there are two ways of looking at the future, and two types of responses. The disaster environmentalists conjour up an inevitable “social collapse” (Bendell), or a “collapse of this civilisation” (Read). Bendell’s proposed response, “deep adaptation”, involves (1) “resilience” to disasters, (2) “people and communities letting go of certain assets, behaviours and beliefs where retaining them could make matters worse”, for example, retreating from unsustainable coastlines or giving up expectations of consumption; and (3) “restoration”, i.e. “people and communities rediscovering attitudes and approaches to life and organisation that our hydrocarbon-fuelled civilisation eroded”, e.g. re-wilding landscapes, changing diets and rediscovering non-electrically powered forms of play. Read’s proposed response is to develop capacity for adaptation to disasters at a local level, and for degrowth economics at a national level.

|

Demonstration in Homs, Syria, at the start of the Syrian uprising,

18 April 2011. Photo: Wikimedia/Creative commons

|

The second way of looking at the future, outlined by Jonathan Neale, sees dangerous climate change exacerbating and combining with existing social conflicts: power and wealth versus people; dictatorships versus masses; corporations versus workers; fascists and religious hatemongers versus communities. Neale avoids proposing neat solutions but offers two lessons. One, that if and when “social collapse” comes to where you are, “people survive, and endure. They learn and come back again” (in the jargon, adaptation). Two, that if people in Darfur, Sudan or elsewhere “make it their business to halt climate change, they can change the world” (in the jargon, mitigation).

Neale makes 100% clear that he does not think that halting climate change, or “changing the world”, will be easy. And I agree with him. But there’s a clear distinction between this approach and that of the disaster environmentalists, who effectively exclude the potential for social transformation.

Look again at Read’s three scenarios: (1) civilisation collapses completely; (2) it collapses but leaves the seeds of a future successor-civilisation; or (3) it “manages to transform itself deliberately, radically and rapidly”.

Read’s message to rich-world populations is: focus on adaptation – and do your best to stop people from the global south migrating here. (Read’s support for rich-world migration controls is discussed by Marianne Brooker of the Ecologist here. Read’s article, and Adam Ramsay’s response, are worth reading too.)

Read’s approach to migration is a gigantic obstacle to building a movement on climate issues that unites people of the global north and south. Paul Kingsnorth has gone further, fashioning a more clearly nationalist environmentalism.[18] The point here is that these ruinous politics are part and parcel of the disaster environmentalists’ opposition to approaching the climate crisis with the hope that society can be changed.

They do not say that changing society is impossible, but insist that this be regarded as an outside chance; that the emphasis is on “deep adaption”, not mitigation. In their letter to Wallace-Wells, Read, Foster and Bendell underline that “really facing up to climate reality […] means giving up all hope of solutions – without giving up on hope itself”. Bendell insists that “any talk of prevention [of dangerous climate change] is actually a form of denial”.[19]

Adaptation versus mitigation is a false dichotomy, in my view. Communities will have to face climate-related disasters. Doing so will be all about confronting power and wealth, which will address these disasters in their own way. The American researcher and activist Ashley Dawson has written a book about this, Extreme Cities, where he analyses the reaction of New York communities to Hurricane Sandy, and puts it in wider context.

The adaptation measures that communities have to fashion are, and will be, intimately linked with the fight to stop the worst climate change from happening. And as Dawson shows, the line-up will again be the same. Power and wealth want business as usual. Communities are urging action – with millions of school pupils, who have mobilised since Dawson’s book was written, now at the forefront.

Protecting ourselves from disaster, and preventing every disaster that we can, involves a fight against the same enemies, who will try to take over the first for their own purposes, and distort and derail the second to the extent that it threatens their power and wealth. There is no way out of this fight. Continue reading at Disaster environmentalism 2: roads to a post-growth economy

[1] Climate Action Tracker‘s “baseline” scenario, which assumes that no political action is taken, projects that by 2100 global average temperature will rise 4.1-4.8 degrees above pre-industrial level; its “current policies” scenario, based on government’s targets, projects a rise of 3.0-3.4 degrees. The UN Environment Programme 2019 Emissions Gap report projects, based on targets agreed at the Paris climate negotiations, projects a rise of 3.2 degrees

[2] Brian Heatley, Rupert Read and John Foster, “Introduction”, in John Foster (ed.), Facing Up to Climate Reality: honesty, disaster and hope (London: Green House, 2019)

[3] Rupert Read and Samuel Alexander, This Civilisation is Finished (Melbourne: Simplicity Institute, 2019) p. 5 and p. 86. The Dark Mountain collective has filled out the idea of civilisational collapse, many years before Read and with literary flourish. For example its bleak manifesto, published by Paul Kingsnorth and Dougald Hine in 2009, urges a literature that focuses on collapse: “human civilisation is an intensely fragile construction. It is built on little more than belief: belief in the rightness of its values; belief in the strength of its system of law and order; belief in its currency; above all, perhaps, belief in its future. Once that belief begins to crumble, the collapse of a civilisation may become unstoppable. That civilisations fall, sooner or later, is as much a law of history as gravity is a law of physics. What remains after the fall is a wild mixture of cultural debris, confused and angry people whose certainties have betrayed them, and those forces which were always there, deeper than the foundations of the city walls: the desire to survive and the desire for meaning.”

[4]Rupert Read, Truth and its consequences, from the first section, “Telling the whole truth”

[5]Jem Bendell, Deep Adaptation: a map for navigating climate tragedy, section on “Framing After Denial”

[6]Jem Bendell, Deep Adaptation: a map for navigating climate tragedy, section on “The Deep Adaptation agenda”

[7]Jem Bendell, Deep Adaptation: a map for navigating climate tragedy, section on “Research Futures in the Face of Climate Tragedy”

[8]Jem Bendell, Deep Adaptation: a map for navigating climate tragedy, section on “Framing After Denial”

[9] Brian Heatley, Rupert Read and John Foster, “Introduction”, in John Foster (ed.), Facing Up to Climate Reality: honesty, disaster and hope (London: Green House, 2019)

[10] Alan Thornett, Facing the Apocalypse, pp. 80-83

[11] Jem Bendell, Deep Adaptation: a map for navigating climate tragedy, section on “Apocalypse Uncertain”

[12] Jem Bendell, “Doom and Bloom: adapting to collapse”, in This is Not a Drill: an Extinction Rebellion Handbook, p. 75

[13] Rupert Read and Kristin Steele, “Making the best of climate disasters”, in John Foster (ed.), Facing Up to Climate Reality p. 54

[14] The other disasters Solnit researched in depth were a 1906 earthquake in San Francisco; an explosion on a ship in Halifax, Nova Scotia, in 1917; and the 1985 earthquake in Mexico City.

[15] Rebecca Solnit, A Paradise Built in Hell, p. 7

[16] Amartya Sen, Development as Freedom, p. 16

[17] Read and Alexander, This Civilisation is Finished, p. 53; Gail Bradbrook presentation at the Womad music festival, 2019

[18] In a noted 2017 article, setting out this type of English nationalism, Kingsnorth wrote: “You want to protect and nurture your homeland – well then, you’ll want to nurture its forests and its streams too. You’ll want to protect its badgers and its mountain lions. What could be more patriotic? This is not the kind of nationalism of which Donald Trump would approve, but that’s the point. The people of any nation will always want the right to control their own borders and decide on the direction of their culture, and England is no exception.” The conclusions about immigration are very clear. He argues that: “The people of any nation will always want the right to control their own borders and decide on the direction of their culture, and England is no exception.” For a really good critique of Kingsnorth’s “volkisch environmentalism”, see Out of the Woods here.

⏭ Keep up with People And Nature.

Disaster Evironmentalism 1: Looking The Future In The Face

Gabriel Levy in the first of a three part series examines the work of Rupert Read on Disaster Environmentalism.

|

The international climate negotiations in Katowice, Poland, in 2018, which were supposed to follow up on the Paris agreements, “can be seen as achieving no more than an elaborate seating-plan for the sun-deck of the Titanic”.

In 2020, countries are supposed to show how they have met the targets set at Paris, and set tougher targets. “But even if a radical programme of reduced emissions was started at that point, and one that went far beyond the Paris Agreement, it would need to achieve zero emissions by 2040 to stay within the 2 degrees C limit. […]

|

|

One demonstration: two approaches.

From the school students’ protest, 29 November, 2019

|

Surely the most optimistic assumption we are entitled to make, based on current political agreements and actions across the world is that emissions will continue to rise after 2030, hopefully levelling off later in the century.

And so “we must assume” that there will be “a global temperature rise associated with carrying on as we are”: that means, by 2100, “at the very least” 3-4 degrees C, and “more likely” 4-5 degrees C.[1]

I agree with all that – with the caveat that those temperatures are consistent with “carrying on as we are”, whereas I believe we have the capacity to do things differently. It is from the Introduction to a new book from the Green House think tank, Facing Up to Climate Reality.[2]

The Introduction argues (i) that “dangerous climate change is now inevitable” and (ii) that “we are going to have to live in a post-growth world”.

This is the starting point of what I call disaster environmentalism, being developed by Rupert Read (one of the Introduction’s three authors), Jem Bendell and other writers associated with Extinction Rebellion (XR).

In a book, This Civilisation is Finished, Read underlines: “there is no ‘safe’ level of warming”; that limiting warming to 2 degrees C, which is now “amost unachievable”, will mean the death of 99% of the world’s coral reefs, and probably the end of ice in the northern hemisphere. It means more extreme weather events, and an increase of violence and war globally. “It is violence: 2 degrees is violence from the rich and stupid against the global masses.” I agree with that, too.

Read goes on to argue that “the climate crisis and the broader ecological emergency of which it is only the most urgent part puts the whole of what we know as civilisation at risk”. And:

By “this civilisation” I mean the hegemonic civilisation of globalised industrial growth capitalism – sometimes called “Empire” – which today governs the vast majority of human life on Earth.

He then presents three possible futures:

- 1 “This civilisation could collapse utterly and terminally, as a result of climatic instability (leading for instance to catastrophic food shortages as a probable mechanism of collapse), or possibly sooner than that, through nuclear war, pandemic, or financial collapse leading to mass civil breakdown.”

- 2. “This civilisation (we) will manage to seed a future successor-civilisation(s), as this one collapses”.

- 3 “This civilisation will somehow manage to transform itself deliberately, radically and rapidly, in an unprecedented manner, in time to avert collapse.” (On one hand, Read adds in a footnote that it is “just about conceivable that this civilisation might survive by adopting an extremely disciplined eco-fascism”, although “such a way of life […] should not properly be regarded as civilised”; on the other hand, elsewhere he says that transforming civilisation would be “the most desirable” option, but “by far the least likely”.)

Disaster environmentalism could be characterised as a trend that deliberately distances itself from the idea that fighting to transform society is necessary and possible.

Read himself counterposes his own view to “virtually everyone in the broader environmental movement” who is “fixated on the third option”. In this, he sees himself in agreement with Bendell; John Foster, co-chair of Green House; Jonathan Gosling, a professor of leadership, and the “Dark Mountain” literary collective.[3]

Read, Foster and Bendell wrote a joint open letter to David Wallace-Wells, author of the best-selling book on climate change, The Uninhabitable Earth, arguing that – while Wallace-Wells had shown how great the danger is – by pointing towards a range of responses aimed at averting it, he was avoiding reality. They called on him to embrace “deep adaptation”, by “accepting that some kind of eco-induced societal collapse is now not merely possible, but likely, and preparing honestly for it”.

|

Carbon Action Tracker’s projections for global temperature, up to 2100

|

Read’s view of our possible futures does not work for me at all.

It is based on a first-world idea of “civilisation” (what, after all, makes global industrial capitalism so “civilised”? and how do we categorise those, such as indigenous peoples in the global south, who have so far managed to live mostly outside its grip?).

It conjours up a Hollywood-movie-style spectre of “social collapse”, at odds with all the fearsome evidence of social crises that we already have in hand. And it comes close to ruling out the prospect of people acting collectively to forestall the worst outcomes.

I do not agree, either, with some of the disaster environmentalists’ practical conclusions, summed up in Read’s call to “focus less on prevention/mitigation (i.e. less on a zero carbon target) and more on adaptation”.[4]

Jem Bendell is more adamant than others, in his paper on Deep Adaptation, that it is too late to forestall disaster. He has “chosen to interpret the information [about climate change] as indicating inevitable collapse, probable catastrophe and possible extinction”[5] – and from this concludes that “deep adaptation”, centred on what he calls “relinquishment” (of things we are used to having) and “restoration”, is the way forward.[6]

This borders on survivalism: “Existing approaches to living off-grid in intentional communities are useful to learn from, but this agenda needs to go further in asking questions like how small-scale production of drugs like aspirin is possible.”[7]

It also borders on much more pessimistic narratives about how the 21st century will unfold. Bendell writes:

There is a growing community of people who conclude we face inevitable human extinction and treat that view as a prerequisite for meaningful discussions about the implications for our lives right now. For instance, there are thousands of people on Facebook groups who believe human extinction is near.[8]

Bendell points out that eschatology, i.e. “reflection on the end of times”, is a major dimension of the human experience”.

This bleak view of the future is related to another aspect of disaster environmentalism which, rather than recognising the huge element of uncertainty inherent in predictions of the future by climate scientists, earth systems scientists, or anyone else, focuses only and deliberately on worst-case scenarios. A good example is the confident assertion by Roger Hallam, one of XR’s founders, of “the slaughter, death, and starvation of 6 billion people this century”.

This seems to me somehow connected with Hallam’s relativising of the Holocaust as “just another fuckery in human history”. This reactionary idiocy has quite rightly been denounced by, among others, XR Germany, XR UK and XR Jews. Good for them. Here I only add that Hallam’s distorted view of the 20th century is linked to a distorted view of the 21st. As he said when apologising for his statement:

I want to fully acknowledge the unimaginable suffering caused by the Nazi Holocaust that led to all of Europe saying ‘never again’. But it is happening again, on a far greater scale and in plain sight. The global north is pumping lethal levels of CO2 into the atmosphere and simultaneously erecting ever greater barriers to immigration, turning whole regions of the world into death zones.

It is not that climate change could cause situations in which Holocaust-like horrors are repeated, but that it is doing so, now, in Hallam’s world. There are no timescales; no doubt; little or no room to act collectively as human beings. There is only “rebellion”, on Hallam’s terms, and catastrophe. This is, in my view, a clear statement of disaster environmentalism.

This three-part article is my attempt at a response. In this first part, I will argue (1) that the disaster environmentalists are right to denounce the international climate talks, and the whole political circus that aims at normalising the causes of climate disasters; (2) that their vision of “social collapse” is deeply flawed; and (3) that, while adaptation – in the sense of facing the consequences of these disasters – is an urgent, near-term, life and death problem, it should not be counterposed to efforts to mitigation, i.e. tackling the causes of greenhouse gas emissions and climate change. In two further parts of the article, I discuss prospects for moving to a post-growth economy, and the practical activity of movements around climate change.

1. The international climate talks are a fraud

Disaster environmentalism smashes through the layers of lies and doublethink that emanate from the international climate talks and are embellished by politicians, oil companies, economists and some big NGOs. Brian Heatley, Rupert Read and John Foster write:

the stark, categorical truth is that things are now certainly going to get worse – much worse – whatever we do. Hardly anyone wants to admit this. It sometimes seems as if almost the entire world is engaged in climate denial – not just those with vested interests in minimising the dangers, but also those working passionately to save us from them.[9]

I agree that things will “certainly” get worse, because, even if greenhouse gas emissions started falling sharply from tomorrow, the effects of those gases already put into the atmosphere will take several more years to take full effect.

Are the disaster environmentalists right to denounce the discourse of illusory hopes surrounding the international climate negotiations? I think so (and said so in 2015, for example).

Another way of looking at the talks is that they have strengthened the movement to tackle dangerous climate change, and that the struggle for an international agreement on climate “has to be fought out alongside many other battles to defend the environment, including direct action”. That’s how the socialist writer Alan Thornett puts it.[10]

I am not against trying to force governments to act, as Thornett urges. But I think we also need to recognise that a central function of the talks process, ever since the Rio convention of 1992, has been to create the illusion that governments are taking care of things, when in fact they are not. To my mind, this is a planetary example of the way that the state functions in society generally: claiming, in increasingly sophisticated terms, to safeguard the common interest, while reinforcing the power and wealth of the ruling class.

Disaster environmentalism strikes a chord, because people now realise just how deceptive the international climate talks have been. The cynicism of politicians that people experience at more local levels is reproduced, with chilling effect, on the global stage. As Greta Thunberg, who initiated the school strikes, said in her speech to the UN climate summit:

How dare you pretend that this can be solved with just ‘business as usual’ and some technical solutions? With today’s emissions levels, that remaining CO2 budget will be entirely gone within less than eight and a half years. There will not be any solutions or plans presented in line with these figures here today, because these numbers are too uncomfortable. And you are still not mature enough to tell it like it is.

It is the specter of disaster, summoned up by thirty years of inaction by the world’s governments, that have provoked the school strikes. The name Extinction Rebellion, and its focus on direct action, have struck a chord missed by older, more incorporated, environmentalist organisations.

This change of mood is the context in which Rupert Read shot to prominence. His refusal in August last year to debate a climate change denier on the BBC, and to turn instead to social media in protest at mainstream media acquiescence in climate science denial, attracted popular support.

The disaster environmentalists connect the Paris paralysis with illusions of “green growth”. They argue that “further net growth, at least in countries like the UK, is neither necessary, desirable, nor possible”. I agree with this, too, but I would add that “green growth” is not a state of mind. It is an ideological construct, used to defend the wealth built out of economic activity, and the power that that wealth exerts. In other words, it is a weapon of the system.

2. A flawed view of “social collapse”

The disaster environmentalists insist that climate change will inevitably (Jem Bendell) or probably (Rupert Read and others) result in “social collapse”. Bendell writes that we are “set for disruptive and uncontrollable levels of climate change, bringing starvation, destruction, migration, disease and war”.[11]

Clearly, we are in a rich country here: “migration” is listed as an external threat, rather than as a strategy to cope with the effects of climate change. Bendell’s dystopia unfolds in classic Hollywood style:

With the power down, soon you wouldn’t have water coming out of your tap. You will depend on your neighbours for food and some warmth. You will become malnourished. You won’t know whether to stay or go. You will fear being violently killed before starving to death.

Bendell specifies that all this is coming over very short timescales:

My guess is that, within ten years from now, a social collapse of some form will have occurred in the majority of countries.[12]

Read and Kristen Steele, in an article on adaptation, have a different view. They warn that storms, drought and wildfires will intensify: “These will be disasters, possibly resulting in the deaths of millions.”[13] Disasters produce collective responses, they emphasise, citing Rebecca Solnit’s book A Paradise Built in Hell.

Solnit researched the aftermath of the New Orleans floods in 2005, the 9 September terrorist attacks in New York in 2001, and other disasters in north America.[14] She summarised her findings by saying that:

the citizens any paradise would need – the people who are brave enough, resourceful enough and generous enough – already exist. The possibility of paradise hovers on the cusp of coming into being, so much so that it takes powerful forces to keep such a paradise at bay. If paradise now arises in hell, it’s because in the suspension of the usual order and the failure of most systems, we are free to live and act in another way.[15]

In none of these situations was the danger of being “violently killed” (who by? one’s neighbours? marauding “others”?) elevated above its normal level in rich-world cities. But that danger is ever-present for people in Yemen, Syria, Afghanistan and other places where various elites – “civilised” ones included – have resorted to military means.

To roll these nightmares together in an imagined, future climate-change-induced disaster, instead of confronting the real ways they are unfolding now – and the real relationship between social crisis and climate crisis – is disarming and potentially demoralising. And it is not telling the truth.

Let’s take a real and frightful example of a social crisis in which climate change played a causal role: Syria.

In 2007-2010, eastern Syria and northern Iraq experienced severe drought: the worst ever recorded. South-eastern Turkey and western Iran were also affected. In Syria, this followed a decade of moderate to serious drought (1998-2007), and was exacerbated by over-mining of groundwater. Harvests were ruined; in 2008, Syria had to import wheat for the first time since declaring grain self-sufficiency in the mid 1990s. Families in the countryside faced economic disaster, and migration into Syria’s cities intensified.

|

| Dry conditions in Syria, 2011. Photo: Joel Bombardier/Creative Commons) |

This in-migration swelled the slums and shanty towns in Syrian cities. When the government cracked down on pro-democracy demonstrators in 2011, these were among the places that exploded in protest. This rebellion merged with the “Arab spring” that swept north Africa and the Middle East.

The outcomes were messy and uneven, and even now are not settled. In Tunisia, power changed hands peacefully. Revolution turned to repression in Egypt and Syria – the latter’s far more deadly and destructive, because of the Bashar al-Assad government’s readiness to kill and torture hundreds of thousands of its own citizens, rather than grant the basic civil rights they demanded.

In 2012-13, Assad opted to militarise his vengeful assault on the population. Russia, the Gulf States (who supported Islamist militias) and the western powers (who tolerated it all) helped. And even in these unimaginably horrible conditions – by far the worst social disaster of the 21st century – there are signs of hope. Right up to today, activists in Syria and in the Kurdish enclave in the north-east refuse the label of victimhood so often fixed to them. They point out that, even now, communities continue to organise, to challenge, to assert their right to shape their lives for the better.

Was Syria’s civil war caused by climate change? A research team led by Colin Kelley of the University of California made that claim. They convinced me that drought caused rural-to-urban migration – but there were many other links to the causal chain, and they had little to say about the social and political ones. The climate scientist Mike Hulme and international relations researcher Jan Selby argued that there was no link: other countries in the Fertile Crescent had suffered drought, but not civil war, they pointed out.

Reading all this, it seemed to me that reality was more complex. I asked Leila al-Shami, co- author of Burning Country: Syrians in Revolution and War, what she thought. She told me in an email:

Climate change and drought was indeed a factor which pushed many rural farmers off their lands and into the overcrowded slums around the cities looking for livelihood opportunities. The uprising broke out first in these affected rural areas and city slums where living standards had plummeted.

But any analysis which states that climate change was the sole factor is both reductionist and completely wrong. That is clear from any analysis of the protesters’ demands in the early days of the uprising – abolition of emergency laws, release of political prisoners etc, as well as socioeconomic justice.

Further, the crisis caused by the drought was largely man made – and due to government corruption. The UN poured in huge amounts of money to address the drought, and affected communities didn’t benefit from it. Also there was a lot of corruption regarding illegal well drilling etc.

Development issues can not be separated from civil and political rights, Leila pointed out – and quoted the Indian economist Amartya Sen, who wrote that economic insecurity often relates to lack of democratic rights and liberties:

It is not surprising that no famine has ever taken place in the history of the world in a functioning democracy – be it economically rich (as in contemporary western Europe or north America) or relatively poor (as in post independence India, or Botswana, or Zimbabwe. Famines have tended to occur in colonial territories governed by rulers from elsewhere […] or in one-party states […] or military dictatorships.[16]

So while climate change contributed to the Syrian disaster, the perpetrator of mass murder was the state. People murdered each other: not marauding bands from a Hollywood dystopia, but people armed and financed by state structures. And this is true of many of the greatest social disasters of the mid twentieth century.

As the socialist writer Jonathan Neale points out, in a comment on Bendell, in all those horrors – the Nazi genocide; the famines in Bengal, Vietnam and China; the atomic bombing of Japan; the Stalinist death camps; and the killings during the partition of India – murder was “by states, and by mass political movements”, not “small groups of savages wandering through the ruins”. He argues that, in those horrors:

Society did not disintegrate. It did not come apart. Society intensified. Power concentrated, and split, and those powers had us kill each other. It seems reasonable to assume that climate social collapse will be like that. […]

Remember this, because when the moment of runaway climate change comes for you, where you live, it will not come in the form of a few wandering hairy bikers. It will come with the tanks on the streets and the military or the fascists taking power.

Those generals will talk in deep green language. They will speak of degrowth, and the boundaries of planetary ecology. They will tell us we have consumed too much, and been too greedy, and now for the sake of Mother Earth, we must tighten our belts.

Then we will tighten our belts, and we will suffer, and they will build a new kind of gross green inequality. And in a world of ecological freefall, it will take cruelty on an unprecedented scale to keep their inequality in place.

That’s an eloquent statement of the reason why tackling dangerous climate change, and resisting ruling elites and their power structures, can not be separated.

If we are to talk about “social collapse” – to my mind a very wide, and potentially meaningless, category – surely Neale’s examples must be considered. He also refers to the long-running military conflicts in Afghanistan, Darfur and Chad as social crises in which climate change has played a role.

The disaster environmentalists have nothing much to say about these real-life crises. Read and Steele refer instead to TV series such as Survivor and The Hunger Games, and the film The Road, and discuss the mainly local, mainly rich-country disasters researched by Solnit.

Disaster environmentalists including Rupert Read and Gail Bradbrook, a spokesperson for XR, point to Collapse, the popular book by anthropologist Jared Diamond, that claims to explain the “collapse” of a series of societies from those of Easter Island and ancient Mexico to Greenland and 20th-century Rwanda.[17]

They seem unaware that Diamond’s approach has been comprehensively critiqued by other anthropologists. His critics argued, many years ago, that he stripped out detail and ignored complex realities in order to justify his theories about unsustainable practices causing societies to collapse. (I wrote about this here in 2012.)

Social crisis, and the way that climate change may cause or aggravate it, is deadly serious. We can not tell the truth about it without some serious analysis.

3. Adaptation and mitigation go together

So there are two ways of looking at the future, and two types of responses. The disaster environmentalists conjour up an inevitable “social collapse” (Bendell), or a “collapse of this civilisation” (Read). Bendell’s proposed response, “deep adaptation”, involves (1) “resilience” to disasters, (2) “people and communities letting go of certain assets, behaviours and beliefs where retaining them could make matters worse”, for example, retreating from unsustainable coastlines or giving up expectations of consumption; and (3) “restoration”, i.e. “people and communities rediscovering attitudes and approaches to life and organisation that our hydrocarbon-fuelled civilisation eroded”, e.g. re-wilding landscapes, changing diets and rediscovering non-electrically powered forms of play. Read’s proposed response is to develop capacity for adaptation to disasters at a local level, and for degrowth economics at a national level.

|

Demonstration in Homs, Syria, at the start of the Syrian uprising,

18 April 2011. Photo: Wikimedia/Creative commons

|

The second way of looking at the future, outlined by Jonathan Neale, sees dangerous climate change exacerbating and combining with existing social conflicts: power and wealth versus people; dictatorships versus masses; corporations versus workers; fascists and religious hatemongers versus communities. Neale avoids proposing neat solutions but offers two lessons. One, that if and when “social collapse” comes to where you are, “people survive, and endure. They learn and come back again” (in the jargon, adaptation). Two, that if people in Darfur, Sudan or elsewhere “make it their business to halt climate change, they can change the world” (in the jargon, mitigation).

Neale makes 100% clear that he does not think that halting climate change, or “changing the world”, will be easy. And I agree with him. But there’s a clear distinction between this approach and that of the disaster environmentalists, who effectively exclude the potential for social transformation.

Look again at Read’s three scenarios: (1) civilisation collapses completely; (2) it collapses but leaves the seeds of a future successor-civilisation; or (3) it “manages to transform itself deliberately, radically and rapidly”.

Read’s message to rich-world populations is: focus on adaptation – and do your best to stop people from the global south migrating here. (Read’s support for rich-world migration controls is discussed by Marianne Brooker of the Ecologist here. Read’s article, and Adam Ramsay’s response, are worth reading too.)

Read’s approach to migration is a gigantic obstacle to building a movement on climate issues that unites people of the global north and south. Paul Kingsnorth has gone further, fashioning a more clearly nationalist environmentalism.[18] The point here is that these ruinous politics are part and parcel of the disaster environmentalists’ opposition to approaching the climate crisis with the hope that society can be changed.

They do not say that changing society is impossible, but insist that this be regarded as an outside chance; that the emphasis is on “deep adaption”, not mitigation. In their letter to Wallace-Wells, Read, Foster and Bendell underline that “really facing up to climate reality […] means giving up all hope of solutions – without giving up on hope itself”. Bendell insists that “any talk of prevention [of dangerous climate change] is actually a form of denial”.[19]

Adaptation versus mitigation is a false dichotomy, in my view. Communities will have to face climate-related disasters. Doing so will be all about confronting power and wealth, which will address these disasters in their own way. The American researcher and activist Ashley Dawson has written a book about this, Extreme Cities, where he analyses the reaction of New York communities to Hurricane Sandy, and puts it in wider context.

The adaptation measures that communities have to fashion are, and will be, intimately linked with the fight to stop the worst climate change from happening. And as Dawson shows, the line-up will again be the same. Power and wealth want business as usual. Communities are urging action – with millions of school pupils, who have mobilised since Dawson’s book was written, now at the forefront.

Protecting ourselves from disaster, and preventing every disaster that we can, involves a fight against the same enemies, who will try to take over the first for their own purposes, and distort and derail the second to the extent that it threatens their power and wealth. There is no way out of this fight. Continue reading at Disaster environmentalism 2: roads to a post-growth economy

[1] Climate Action Tracker‘s “baseline” scenario, which assumes that no political action is taken, projects that by 2100 global average temperature will rise 4.1-4.8 degrees above pre-industrial level; its “current policies” scenario, based on government’s targets, projects a rise of 3.0-3.4 degrees. The UN Environment Programme 2019 Emissions Gap report projects, based on targets agreed at the Paris climate negotiations, projects a rise of 3.2 degrees

[2] Brian Heatley, Rupert Read and John Foster, “Introduction”, in John Foster (ed.), Facing Up to Climate Reality: honesty, disaster and hope (London: Green House, 2019)

[3] Rupert Read and Samuel Alexander, This Civilisation is Finished (Melbourne: Simplicity Institute, 2019) p. 5 and p. 86. The Dark Mountain collective has filled out the idea of civilisational collapse, many years before Read and with literary flourish. For example its bleak manifesto, published by Paul Kingsnorth and Dougald Hine in 2009, urges a literature that focuses on collapse: “human civilisation is an intensely fragile construction. It is built on little more than belief: belief in the rightness of its values; belief in the strength of its system of law and order; belief in its currency; above all, perhaps, belief in its future. Once that belief begins to crumble, the collapse of a civilisation may become unstoppable. That civilisations fall, sooner or later, is as much a law of history as gravity is a law of physics. What remains after the fall is a wild mixture of cultural debris, confused and angry people whose certainties have betrayed them, and those forces which were always there, deeper than the foundations of the city walls: the desire to survive and the desire for meaning.”

[4]Rupert Read, Truth and its consequences, from the first section, “Telling the whole truth”

[5]Jem Bendell, Deep Adaptation: a map for navigating climate tragedy, section on “Framing After Denial”

[6]Jem Bendell, Deep Adaptation: a map for navigating climate tragedy, section on “The Deep Adaptation agenda”

[7]Jem Bendell, Deep Adaptation: a map for navigating climate tragedy, section on “Research Futures in the Face of Climate Tragedy”

[8]Jem Bendell, Deep Adaptation: a map for navigating climate tragedy, section on “Framing After Denial”

[9] Brian Heatley, Rupert Read and John Foster, “Introduction”, in John Foster (ed.), Facing Up to Climate Reality: honesty, disaster and hope (London: Green House, 2019)

[10] Alan Thornett, Facing the Apocalypse, pp. 80-83

[11] Jem Bendell, Deep Adaptation: a map for navigating climate tragedy, section on “Apocalypse Uncertain”

[12] Jem Bendell, “Doom and Bloom: adapting to collapse”, in This is Not a Drill: an Extinction Rebellion Handbook, p. 75

[13] Rupert Read and Kristin Steele, “Making the best of climate disasters”, in John Foster (ed.), Facing Up to Climate Reality p. 54

[14] The other disasters Solnit researched in depth were a 1906 earthquake in San Francisco; an explosion on a ship in Halifax, Nova Scotia, in 1917; and the 1985 earthquake in Mexico City.

[15] Rebecca Solnit, A Paradise Built in Hell, p. 7

[16] Amartya Sen, Development as Freedom, p. 16

[17] Read and Alexander, This Civilisation is Finished, p. 53; Gail Bradbrook presentation at the Womad music festival, 2019

[18] In a noted 2017 article, setting out this type of English nationalism, Kingsnorth wrote: “You want to protect and nurture your homeland – well then, you’ll want to nurture its forests and its streams too. You’ll want to protect its badgers and its mountain lions. What could be more patriotic? This is not the kind of nationalism of which Donald Trump would approve, but that’s the point. The people of any nation will always want the right to control their own borders and decide on the direction of their culture, and England is no exception.” The conclusions about immigration are very clear. He argues that: “The people of any nation will always want the right to control their own borders and decide on the direction of their culture, and England is no exception.” For a really good critique of Kingsnorth’s “volkisch environmentalism”, see Out of the Woods here.

⏭ Keep up with People And Nature.

No comments