Gabriel Levy in a piece last month focuses on a book to highlight the bloody poppy culture and its associated racism.

The vindictive, cowardly racism that black Britons face on the streets is rooted in empire, the hip-hop artist and writer Akala insists in his book Natives: Race and Class in the Ruins of Empire.

|

| Akala. Photo: Alexis Chabala / Two Roads books |

As much as a tendency to dominate, divide and brutalise has been a seeming constant for the past few millennia at least, so too has the tendency of sharing and co-operation, of rebellion against dominant powers and attempts to create a more just order - Akala writes (p. 148).“The degree to which humans have secured a more just world has been born out of the struggles against empires as much as anything else.”

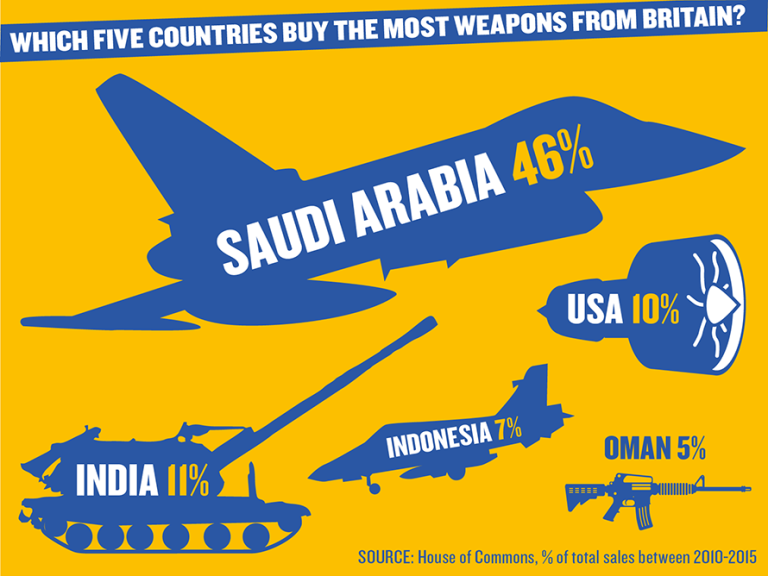

Akala recounts the British empire’s crimes – from slavery, through colonialism in Africa to selling weapons to Saudi Arabia for the genocidal onslaught in Yemen right now – and denounces historians such as Niall Ferguson who try to paint the empire in positive colours. When a survey found that 59% of Brits were proud of empire, Ferguson gloated on twitter: “I won”.

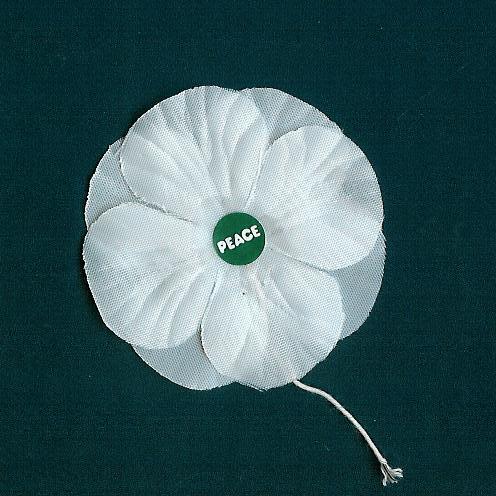

Akala’s response is especially relevant this week, when pro-imperial hypocrites are proudly sporting their red poppies:

While I’m sure Mr Ferguson and others would accuse me of ‘working myself up into a state of high moral indignation’ about the crimes of the British empire, I’ll bet that he and others like him will be wearing their poppy every 11 November; that is, they will be ‘working themselves up into a state of high moral indignation’ about dead people, when those dead people are truly British – the Kenyans tortured in the 1950s were legally British citizens but naturally there will be no poppies or tears for them. The implications are clear – some ancestors deserve to be remembered and venerated and others do not. Those that kill for Britain are glorious, those killed by Britain are unpeople. If we truly cared for peace, would we not remember the victims of British tyranny every 11 November too?You’re right there, Akala.

The chapter of Natives that ends with that denunciation begins with Akala’s memory of how, as a precociously clever seven-year-old, he was shown a painting of William Wilberforce by his teacher. “This man stopped slavery”, she said.

‘What, all by himself miss?’ I asked. ‘Don’t you mean, he helped?’ Her face distorted, and she took the exact same flustered breath that liberals everywhere would take in 2008, right before they were about to lecture any black person who had the gall to declare themselves a non-supporter of Barack Obama.

Akala reminds us of the three things you will learn about transatlantic slavery at schools in the UK: “(1) Wilberforce set Africans free; (2) Britain was the first country to abolish slavery (and did so primarily for moral reasons); (3) Africans sold their own people.” The first two are “total nonsense”, the third a “serious oversimplification”, he argues.

Denmark abolished slavery in 1792, and France did so temporarily in 1794. But the most important abolition, before the British empire’s in 1807, was by Haiti –where rebellious slaves drove out the slaveowners, defeated the French and British imperial forces that tried to re-enslave them, and supported the independence declaration of 1804.

Akala sets out these historical facts, demolishes the claim that the British empire’s abolition was motivated by moral, rather than commercial, considerations, and discusses the issue of African slave traders with a nuance sadly missing from the school curriculum.

And through his whole eloquently argued, thoughtful book, he draws the connections between the revolting racism faced by twenty-first century black Britons with the history of empire and class struggle.

I am a fair bit older than Akala – let’s be honest, old enough to be his dad – and I think it’s great that young people who follow his music may also, through this book and his Youtube videos (e.g. here, here, here or here), engage with his arguments about history. Buy the book for your teenage relatives!

|

I know many people’s motivation for wearing red poppies are genuine. But plenty of politicians and public figures wear them while simultaneously endorsing war, and the British empire that did and does so much to cause it. I hate these lying hypocrites, who sport their poppies while supporting the UK’s fading, but still lethal, warmongering in Iraq, Afghanistan, and elsewhere. I hate politicians’ silence about the UK’s arms sales business. And I hate the increasingly strident public attacks on those who don’t wear a red poppy.

Symon Hill of the Peace Pledge Union wrote a terrific response to the right-wing idiot Piers Morgan, who unsuccessfully tried to bully him on TV for wearing a white poppy. And James McClean, the Stoke City footballer, has once again insisted he won’t be wearing a red poppy. It’s worth reading his letter to Dave Whelan, chairman of Wigan, that he wrote when he played there, reproduced in full here, and this comment article by Eamonn McCann.

■ The Peace Pledge Union information on white poppies and basic info as told by the Independent

■ The Black Poppy Rose group (remembering black servicemen and women), and its facebook page

■ Veterans for Peace UK articles on the white poppy

■ Natives: Race and Class in the Ruins of Empire, by Akala is published by Two Roads. On Amazon here.

|

That question about the empire...they asked the wrong people. They should have put that question to those who laboured under its huge weight...different response would follow.

ReplyDeleteWhat they did was to ask the Romans if the Roman Empire was good or bad!

Akala is a fraud.

ReplyDeleteWolfe Tone

ReplyDeleteI wonder why you say Akala is a fraud. I thought you would be on-message with everything he says about racism, Empire and the red poppy.