Christopher Owens reviews a collection of short stories.

|

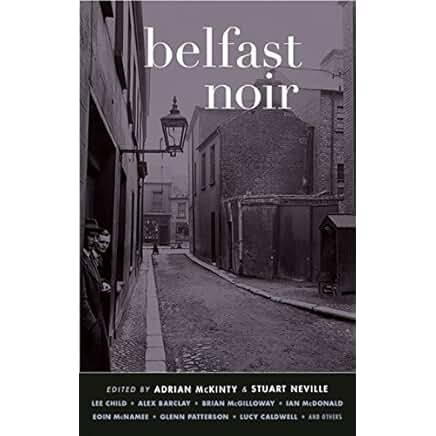

| Add caption |

A good short story collection should be something that can

be dipped into at leisure and enjoyed in isolation. The best ones, however,

have a flow and rhyme to them that connect all the stories, no matter how

disparate the writing style, and make the reader feel they're reading a proper

novel.

There are examples of such a thing: The Informers by Bret Easton Ellis, War All the Time by Charles Bukowski, Dubliners, Metamorphosis and

Other Stories. It's an art form in itself, and a highly underrated one.

So this collection, first published in 2014, has the

capability of joining the illustrious ranks of the ones above, because each

story is set in a different part of the city. Going from the historical

battlefield of the Falls Road, through to the leafy suburbs of Dundonald and

the grim, decaying streets of the Shore Road, there is a lot of scope here for

the writers to explore.

On top of that, you have the term 'noir' and all the usual

connotations. A lot of people just think it means 'dark', but it's so much more

than that. The best noir conjures up an amoral world where supposed heroes are

more corrupt than the supposed bad guys and cynicism runs through every page.

The introduction sets the tone pretty well:

Few European cities have had as disturbed and violent a history as Belfast over the last half-century. For much of that time the Troubles (1968-1998) dominated life in Ireland's second largest city, and during the darkest days of the conflict - in the 1970s and 1980s - riots, bombings and indiscriminate shootings were tragically commonplace. Reflecting a city still divided, 'Belfast Noir' serves as a record of a city transitioning to normalcy, or perhaps as a warning that underneath the fragile peace darker forces still lurk.

Fertile ground for the creative mind, certainly. But does Belfast Noir stand up to this hyperbole?

Truthfully, it does and it doesn't.

When it does, it's less about the plots and more about the

atmosphere on display. Take Lucy Caldwell's brilliantly twisted 'Poison', where

a young woman has a chance sighting in a bar that triggers memories of past

liaisons as a school girl. When you're reading it, you find yourself sucked

into the listless suburbs that remained untouched by the violence, but always

had a certain tension regardless.

The perfect example is the legendary Eoin McNamee's

inclusion, 'Corpse Flowers', the most enjoyable and striking piece in this

collection. Written in the form of a report, switching from CCTV camera to

press conferences, it's an engrossing search for a murderer written in that

distinctive McNamee style. A mix of the gritty, the esoteric and an awareness

of how the past suffocates the present. It's intoxicating.

Take this for example:

You could see tramlines in the car park surface. The grid lines of long-gone streets. Men in belted coats standing at intersections, drab-suited kapos. Cold War phantoms. Letting you know you'd come under their remit. Their ghost authority.

Retreading

hallowed ground does that to the mind, and McNamee's ability to tap into this

section of our subconscious marks him out as a genuinely unique Irish writer.

Gerard Brennan's 'Ligature' is an ambitious attempt to tell

a tale from the perspective of a teenage girl in Hydebank Young Offenders

Centre. It doesn't work in places, due to the narrative being a bit too linear

for this sort of person, but it manages to pull together for the chilling

denouement.

Other stories do a decent job, but don't connect in the same

way. Garbhan Downey's 'Die Like a Rat', if included in another anthology, could

be considered an amusing and persuasive piece about the power that woman can

exude over men. Here, it feels like an outtake from a Guy Ritchie movie.

Likewise, 'Rosie Grant's Fingers' (written by Claire

McGowan). Maybe if expanded into a longer tale and included elsewhere, it could

be seen as enjoyable pot boiler material. Here, it feels incongruous and the

local references quite laboured.

The most puzzling inclusion (and certainly the weakest

story) is Ruth Dudley Edwards' tale 'Taking it Serious.' On it's own merit,

it's a well crafted story with an ending that somehow reminded me of the ending

for Butch Cassidy and the Sundance Kid.

However, despite it having virtually nothing to do with noir, what really

irritates is her heavy handed metaphors (an autistic teenager involved in

dissident republicanism and an "in the closet" former Provo who can't

bring himself to admit his former organisation were defeated).

Of course, anyone who is aware of her writings will know of

her political leanings, and it's certainly not uncommon for a writer crafting a

story (be it a short one or a novel) to include some of these views in the

plot. But metaphors of this ilk should be subtle, not bludgeoning.

In conclusion, it's a good collection that threatens to be

great but falls short. Someone needs to take this format and write the ultimate

short story collection about Belfast. We live in a fascinating time, always in

a state of becoming but never actually being. Imagine someone taking that

setting, throwing in the clipped prose of James M. Cain and the arcane

worldview of Neil Gaiman.

That would be the greatest short story collection ever.

Belfast Noir edited by Adrian McKinty and Stuart Neville. Akashic. ISBN-13: 978-1617752919

Christopher Owens reviews for Metal Ireland and finds time to study the history and inherent contradictions of Ireland.

Follow Christopher Owens on Twitter @MrOwens212

No comments