|

After nearly seventeen years, I can respond without hesitation when asked what experience has had the most profound impact on my psyche, and my life. Admittedly, exercising this confession has not been without trepidation. However, I have since recognised my response was learned from a culture of childhood religious indoctrination, one that crippled me from seeking help or comfort from those who I loved when I most needed it, following this incident of trauma.

Since having recognised the source of this shame I carried within myself, I have concluded that my struggle to navigate this experience has created a unique opportunity for me to become a wiser, stronger version of my myself – our ghosts can become our teachers – we can become capable of demonstrating to others how not to suffer in misguided shame and anguish for the sake of upholding empty notions perpetuated by faith. And importantly that it is often in our darkest moments that we find the courage to survive what can seem impossible circumstances.

I had what could be considered a privileged and idyllic childhood, a dual Australian/American citizen growing up in Boulder, Colorado with my two younger siblings and parents. There were not many memories I can recall as being negative in my childhood, apart from the generic struggles one would expect with adjusting to new schools. The exception to this was the constant source of weekly conflict – the tantrums that inevitably arose each Sunday when I was bade to attend church.

Being raised as a Catholic and being a restless child, I was never a fan of the solemn, stuffy, cold building, or the sternness with which I was commanded to sit, stand, kneel, sit again. Mostly, however, I was always dubious of the irony of being told that Santa and the Easter Bunny were imaginary, yet this equally implausible Bronze-Age ‘God’ was real. He seemed, and still seems, as much an imaginary friend as any of the other popular fictitious characters children are tricked into fawning over.

Our family took a summer vacation to a nice village in the Rocky Mountains when I was 13 in Grand Lake, and being the independent and adventurous kid that I was, I set off to explore in the village while my family went shopping. I could never have imagined that I would end up in a white van being abducted by a stranger, and transported to a remote destination in the forest.

Being told to ‘drink this’ and after declining, and witnessing façade of the strange man change from a predatory smile to open scorn – In that moment, for the first time in my life, I was aware of an almost primitive fear that rose within me, and all at once I was certain that my life was in danger. I knew that I was captive, and being paralysed in a state of disbelief, I took the drink and consumed it as he commanded. The events that unfolded in my conscious memory has been inaccessible from that point on, except for flashes of running for my life in the hopes of navigating my way through the forest and back to the town. Limping, disoriented, and intoxicated, I made it back to the town after being offered a lift. At the time all I could think of when I got home was the dread in “what will happen if my parents find out”, and “how can I make sure they don’t find out how I have shamed them”?

The gravity of the situation I could not fully comprehend at that very moment. Although I was deeply haunted by my experience I was immobilised with shame, and the thought of confessing what had happened to me made me recoil with dread. I ardently believed that I would be judged for what I had gone through, that I was a stupid girl for letting it happen, and I was therefore incapable of bringing myself to what I believed would be perceived by others as making me dirty and stupid.

It was not until several weeks later when I returned to school that I had the courage to confide in a friend I had made. In the end, the only motive that compelled me to sharing this nightmare was the terrifying thought – could I be pregnant? I had no recollection of what had actually happened that day, but retrospectively, the symptoms lead me to some uncomfortable possibilities.

Like most girls my age, I was not comprehensively educated in sexual education, and was certainly not prepared for considering what the consequences of rape could mean for me. My life had all at once been turned upside down. Never had I ever considered pregnancy or motherhood, and I was certainly not prepared or willing to carry through with either.

I was so ill equipped to deal with the situation. I had no idea who I could turn to for questions, or if I was even entitled to confidentiality to ask for help. My primary concern was to ensure that nobody knew this awful secret.

Realising the horror of the worst-case scenario, I know without any trace of a doubt that I was absolutely prepared to follow through with whatever measures were necessary to ensure that my family never found out about what had happened. I was determined to take back control of myself, and to remove any evidence that this incident ever happened, regardless of the risk to my life. I ardently believed that a life of shame was not one worth living.

The enduring and pervasive stigma of feminine purity commonly perpetuated by all of the Abrahamic religions; Christianity, Islam, Judaism, or in my experience, Catholicism – compelled me to acquiesce into painful silence.

As a little girl I learned through active teachings a strict code of conduct for women and young girls – different to those expected of men and boys. This was preached by the Catholic church, passively conveyed through the popular media, demonstrated in my school, my neighbourhood and my community.

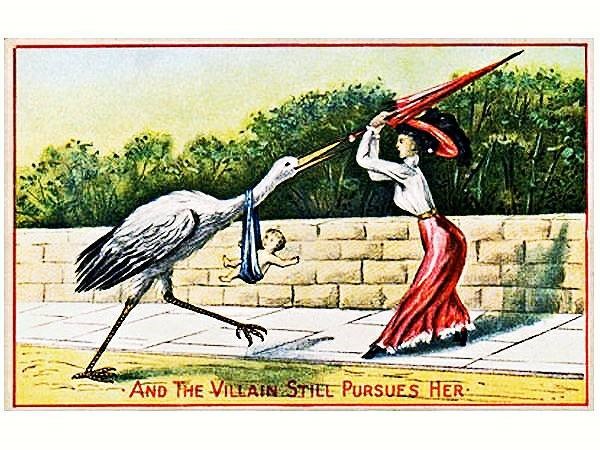

This indoctrination teaches us as children to believe that female was dirty, impure, immoral and undesirable – it was demonstrated to me through popular (Christian) culture and through the use of common derogative epithets applied strictly to women, such as whore and slut, along with all of the other horrid terms used to smear “immodest” women who have “no dignity” by having sex outside of wedlock, whether that sex be consensual or not. The fundamental flaws I see in this stigma (apart from the fact it is an outdated and ridiculous religious ideology) in a modern context I will do my best to objectively unpack, having spent over a decade rationally reflecting upon and considering beyond the bonds of misogynistic religious idiocy.

Now the works of the flesh are evident: sexual immorality, impurity…and things like these. I warn you, as I warned you before, that those who do such things will not inherit the kingdom of God. ~Galatians 5:19-21

The fundamental flaws I see in this stigma (apart from the fact is an outdated religious ideology) in a modern context I will do my best to objectively unpack, having spent over a decade of consideration, disdain, and frustration to rationalise through my own meandering experience.

It could be argued that the basis of such a law, as written in ancient texts was simply devised as a matter of practicality: ensuring that offspring begotten from the one of the most basic of human instincts, that of replication – were provided for accordingly. Thus, ensuring the mothers and children resulting from such communions did not become a burden reliant on the charity of the institution.

By creating the concept of virtue – it may have been considered in the interests of women by ensuring their security, and that of their children by deeming it socially unacceptable to fornicate before both man and woman were recognised through ceremony as committing themselves to being together before consummating.

Regardless of whether or not this is considered a valid explanation behind the creation of this lingering double standard – the fact still stands – this value has become obsolete in modern society – or at least in developed countries, where access to contraception and birth control is available to give people the choice as to whether or not they are prepared to commit themselves to the tremendous responsibility of bringing life into the world and becoming a parent.

This virtue of purity ‘The Virginity Stigma’ as I have come to identify, is the foundation for the undue shame and misery endured by so many who may experience sexual or emotional abuse for experiences that are beyond their control. I endured this shame silently for years – a shame that kept me from turning to those who loved me – who I would have otherwise looked to for support and guidance to deal with such a trauma.

The persistence of this lingering theocratic construct should be acknowledged for what it is, as it is simply not accommodating to those who are victims of circumstance. Additionally, it continues to permeate the fabric of the victims’ freedoms, by subjugating and denying reproductive autonomy to those already consumed with what in many cases already an emotionally impossible situation purely on the basis of outdated scripture which cannot possibly take into account the advances of modern medicine.

The effects of this toxic and outdated notion can result not only in a deeply held sense of shame, it can also result in the stunting your personal relationships with family and many cases it may render victims unable to trust their judgement enough to enjoy or even want to engage in meaningful, fulfilling sexual relationships as an adult.

It could be argued that the basis of such a law, as written in ancient texts was simply devised as a matter of practicality: ensuring that offspring begotten from the one of the most basic of human instincts, that of replication – were provided for accordingly. Thus, ensuring the mothers and children resulting from such communions did not become a burden reliant on the charity of the institution.

By creating the concept of virtue – it may have been considered in the interests of women by ensuring their security, and that of their children by deeming it socially unacceptable to fornicate before both man and woman were recognised through ceremony as committing themselves to being together before consummating.

Regardless of whether or not this is considered a valid explanation behind the creation of this lingering double standard – the fact still stands – this value has become obsolete in modern society – or at least in developed countries, where access to contraception and birth control is available to give people the choice as to whether or not they are prepared to commit themselves to the tremendous responsibility of bringing life into the world and becoming a parent.

This virtue of purity ‘The Virginity Stigma’ as I have come to identify, is the foundation for the undue shame and misery endured by so many who may experience sexual or emotional abuse for experiences that are beyond their control. I endured this shame silently for years – a shame that kept me from turning to those who loved me – who I would have otherwise looked to for support and guidance to deal with such a trauma.

The persistence of this lingering theocratic construct should be acknowledged for what it is, as it is simply not accommodating to those who are victims of circumstance. Additionally, it continues to permeate the fabric of the victims’ freedoms, by subjugating and denying reproductive autonomy to those already consumed with what in many cases already an emotionally impossible situation purely on the basis of outdated scripture which cannot possibly take into account the advances of modern medicine.

The effects of this toxic and outdated notion can result not only in a deeply held sense of shame, it can also result in the stunting your personal relationships with family and many cases it may render victims unable to trust their judgement enough to enjoy or even want to engage in meaningful, fulfilling sexual relationships as an adult.

Experiencing repressed sexual abuse can cultivate a self-loathing that can lead to anxiety and depression – and in the most extreme cases, suicide. In instances such as my own, where I was provided with an exemplary upbringing with supportive parents who I have no doubt would have done anything to ensure my safety and support – had they known – if not for theses religious teachings of shame and the cultural value of purity otherwise rendering me paralysed from seeking help, for fear of shame and embarrassment.

You don’t need to call yourself a feminist, nor even an atheist to acknowledge the derogative nature of this absurd and outdated idea, and I would add that most people who have suffered will never speak of their experience, and thus, I would be willing to wager that there is a good chance that someone who you know and love may have a secret like mine. They might even choose not to share it with you, but in displaying the courage to dispel the ‘Virginity Stigma’, you are telling them that it their value is not rooted in their virginity, but in their character and in the courage of their credible convictions.

No comments