Seamus Mallon Told The Truth About John Hume – But Then Sinn Fein Played Everyone, IRA Included, Like A 3lb Trout

|

| Playing a trout on a fly fishing line |

I mean, they used John, John Hume, like you’d play a three pound trout, and he gave them the thing that they were looking for – and that was a respectable image in the United States.” – Former SDLP deputy leader, Seamus Mallon, interviewed on BBC radio, December 28th, 2015

|

| Seamus Mallon and John Hume meet the media during the Good Friday talks |

|

| Charles Haughey, pictured in his Kinsealy mansion |

You have to understand that while Adams was trying to talk to me he was also approaching Hume and my decision to nominate Hume as my representative, which was my first instinct, happened at the same time, it was contemporaneous. I think this was just a little after they had had a secret meeting. – Author’s note of interview with CJ Haughey, December 1st, 1999

|

| Fr. Alec Reid, ‘an sagairt’ – the go between for Adams and Haughey |

The visits from Reid started in 1985 – as evidence here is a message from Gerry Adams to me dated 15-1-86 which shows that it must have started in 85 – (although I) can’t remember when in ‘85…..Adams had already (by time of first Reid approach) decided to look for an alternative to armed struggle. – Author’s note of interview with CJ Haughey, December 1st, 1999

It would have been towards the end of August 1993 when I made the journey to the Everglades Hotel in Derry. It had been some time since SDLP leader John Hume and myself had met but a series of startling, not say baffling events during the preceding months had made a get-together long overdue.

In April, the existence of the so-called Hume-Adams talks had been divulged when, by chance or design, Gerry Adams had been spotted visiting John Hume’s home in Derry (hardly the wisest choice for a hush-hush assignation and the cause thereby of various conspiracy theories suggesting that both men, or one or the other had contrived the disclosure).

To put this into context, one has to remember that back in the early 1990’s no respectable/ambitious Irish or British politician would dare to breathe the same air as Gerry Adams (and, though they will not like to be reminded now, neither would a clear majority of the Irish press corps!), since to do so suggested insufficient condemnation of, ambivalence towards and even approval of the use of political violence.

|

| John Hume and Gerry Adams meet in a BBC radio studio – Hume was known as ‘Sean’ in Adams’ secret dialogue with Charles Haughey |

The very fact that the two men who represented the opposite poles of Northern Nationalism, one a pariah in many eyes, the other an Irish Gandhi, had shared a roof even for a few minutes, was a sensational story.

For the record, Eamonn McCann had been told of the Adams’ visit by a friend and had phoned my newspaper, The Sunday Tribune with the news. Although a frequent writer for the Trib, McCann was, for reasons I never discovered, not keen to write the story himself and so it was passed on to me by the newsdesk.

|

Eamonn McCann

|

When I rang Hume for confirmation, he at first denied the story but then a few minutes later he rang back to confirm that the two men had indeed met and furthermore had held “extensive discussions”. What this exchange said about the conspiracy theories is anybody’s guess.

We learned a little more about what these “extensive discussions” amounted to a fortnight later when the two men met again, this time at a more discrete location, when they issued a lengthier statement explaining their intent. Whether we were any the wiser is debatable since their words could have been, and may well have been composed by a Jesuit, or at least a Redemptorist.

The phrase that had us all wringing our brains were these two paragraphs, clearly the central strut of their dialogue:

We accept that the Irish people as a whole have a right to national self-determination. This is a view shared by a majority of the people of this island though not by all its people.

The exercise of self-determination is a matter for agreement between the people of Ireland. It is the search for that agreement and the means of achieving it on which we will be concentrating.

What on earth did this mean? We know now. It is as clear as day. It is called the Good Friday Agreement and at its core is an acquiescence to the consent principle tempered by power-sharing. But back then it was not as possible to detect such clarity, not least just because the formulation was soaked in ambiguity but the necessary precondition, that the IRA would abandon violence was, well, unattainable, or so it seemed.

As if to underline that thought, on the day the two men met for the second time to spell out their intentions, the IRA exploded a one-ton lorry bomb in the Bishopsgate section of the City of London, costing one man his life, injuring thirty and causing damage estimated at between £Stg 300m and £Stg 1,000m ($450m – $1,500m).

It was one of the most destructive and probably the most expensive bombs of the Troubles. Anyone tempted to discern a sellout in the Hume-Adams statement had their suspicions blunted by the devastation visited upon Britain’s financial heart.

|

| The Bishopsgate bomb – devastated the City of London on the same day Hume and Adams held their second meeting |

It was the start, but by no means the end, of a frustrating dance of the antithetical that would last, seemingly, forever, one day pointing towards some sort of peaceful resolution, on another towards ….. well, that was never clear except whatever it was Northern Ireland wouldn’t ever be quite the same again.

It took a long, long time to realise that this was actually the engine of the peace process in motion, working rather like the positive and negative poles of a magnet, their conflicting pulls and pushes sufficient to keep most passengers if not content, then at least in their seats as the process chugged along.

At the end of May, the voters gave their verdict on these tentative and confusing moves, the Hume-Adams dialogue in particular. Sinn Fein’s vote rose by two per cent, the SDLP’s fell by 1.5%. Nationalist voters had liked what they saw and the message to Sinn Fein was clear: keeping talking to Hume and more of us will vote for you. Peace talks brought their own reward.

The day after the election, as the votes were being counted, the negative pole on the magnet clicked. The IRA planted a 1,000lb car bomb near the HQ of the Ulster Unionist Party, injuring thirteen and causing £6.5m ($10m) of damage, mostly to the Grand Opera House. The next day a huge bomb devastated the centre of Portadown, Orangeism’s citadel, and the day after Magherafelt in South Derry, another Unionist stronghold, was blasted.

A few days later the Irish President Mary Robinson flew to London for the first ever meeting between a serving Irish president and a British monarch. Why this happened became clear three weeks later when Robinson drove to West Belfast and in the same Ballymurphy school where twenty-two years earlier, IRA leaders had hailed the failure of internment, met and shook the hand of Gerry Adams, albeit out the sight of the media and their cameras.

|

| President Mary Robinson and Queen Elizabeth meet in London |

Meeting the Queen was a preparatory balancing act for the Adams’ encounter, evidence that more than one participant in this process was fishing with a fly rod. Again there was a coded message which was that in the right circumstances Mr Adams and his political colleagues could enjoy all the benefits of political respectability in the Southern state, not least unfettered media coverage.

But those guys who had just wreaked destruction in three town centres and the City of London would have to be reined in.

The other pole of the magnet clicked and the machine moved on.

And so, against this perplexing background, I thought it was well beyond time that I found out what one of the two men at the centre of events thought of all this.

I was about an hour away from the Everglades when the car radio broke news that a high-powered Irish-American delegation, led by Congressmen Bruce Morrison and containing one billionaire and a captain of Wall Street in its number (‘Chuck’ Feeney and Bill Flynn), was coming to Ireland for a one week fact finding visit, the highlight of which would be a face-to-face meeting with Messrs Adams and McGuinness.

(It later transpired that the IRA had also organised a one week ceasefire to coincide with their visit.)

This was a startling development with significant meaning. If respectable US politicians and businessmen thought it was okay to meet the Provo leadership to talk about whatever it was Adams and Hume were discussing then surely a) what Adams and Hume were discussing must be meaningful and b) it could only be a matter of time before the Irish and British governments did the same.

John Hume arrived late for our lunch and I assumed the breaking news was responsible. But his face was blank when I asked him about the planned visit. He knew nothing about it and left the table to check. When he came back he was not in the best of moods and openly, even angrily questioned the motives of people (the Irish-Americans) meddling in the peace process without his approval or knowledge.

In all this, I am conscious that John Hume is not in a position to answer, much less counter this version of events but I present it in good faith as being an accurate representation of what happened that day.

In retrospect, I suppose this was the moment when I began to think that the peace process was not what it seemed or what we believed it to be.

Ever since the discovery of their clandestine encounter in April, the peace process was assumed to be centred on the Hume-Adams’ talks.

I already had great difficulty with this concept. Assuming this was an honest exchange of views, Hume would try to win Adams over to constitutional political principles which in Northern Ireland has always meant accepting the status quo and the conventional orthodoxy that the place will remain British until sufficient numbers of Unionists say otherwise. In the meantime, Hume would preach, Nationalists should try to heal politics via power-sharing and other consensual measures.

How could Adams deliver such a heresy to the IRA and hope to survive, even if he himself might be open to the approach?

And now, in the wake of the Everglades lunch (which proceeded awkwardly to a hurried conclusion), I was left with the distinct impression that we were not being told the truth about the Hume-Adams’ process.

|

| Charles ‘Chuck’ Feeney – the American multi-billionaire was a leading figure in the Irish-American pressure group which met Gerry Adams & Martin McGuinness during a week long IRA ceasefire. John Hume knew nothing of their plans until told by the author |

After all, if a powerful delegation of American politicians and businessmen could organise a week long tour of Ireland with its high point being a meeting with Gerry Adams, as well as a week long IRA ceasefire while Adams’ confrere in the peace process, John Hume, was blissfully ignorant, then there was only one conclusion to be made. The action was also happening elsewhere, maybe mostly elsewhere, and the process was a whole lot more complicated than it appeared.

To cut a long story short I came much nearer the truth a few months later when I was able to persuade the former Irish prime minister Charles Haughey to share with me his memories of the early years of the process as well as documentary evidence to support his recollections.

Gerry Adams, via Fr Alex Reid and, in a minor role, the former Irish Press editor, Tim Pat Coogan, had approached Charles Haughey while he was in opposition to explore proposals to end the violence. Haughey’s memory was that this was sometime in 1985, by which time, he believed, Adams had decided to seek an alternative to armed struggle.

Haughey agreed and a line of communication – Adams via Reid to trusted adviser Martin Mansergh, on Haughey’s behalf – was set up. Adams never had face-to-face contact with Haughey but the distinction was academic.

|

| Haughey’s loyal aide, Martin Mansergh who fronted for him during the contacts with Gerry Adams |

It was a very risky venture for Haughey given his colourful history as an alleged facilitator of arms smuggling to the IRA back in 1970, a scandal that for a while looked as if it could send him to jail and political oblivion.

He survived to make a remarkable political comeback but had a word emerged of this secret dialogue with the Sinn Fein leader, even when it was conducted via a Catholic priest, Haughey could be destroyed and he knew it.

For that reason he insisted that John Hume – code-named ‘Sean’ in their furtive messages – would take his place in the discussions as his representative or nominee, a proposal that Adams reluctantly accepted on behalf of ‘his friends’ (a coded reference to the Army Council?) as long as Haughey promised to restore the link at the appropriate time and kept a line open via ‘an sagairt‘, i.e. Fr Reid. (see quote at top of post)

Haughey went on to tell the author that when Hume was approached and asked to undertake this role not a mention was made of the lengthy and quite detailed prior diplomacy involving Haughey.

This, Haughey said, was a precaution based on the possibility that Hume might leak the story, either because he was incapable of keeping it a secret or to do Haughey harm.

And so John Hume accepted his role as the intermediary with Gerry Adams on the mistaken assumption that he was the first and sole point of contact with the IRA’s political leader and was thus the man who really and only mattered. The truth was more prosaic; he was one of many contacts but circumstance and the self-interest of others had elevated him, in his own eyes, to a mythic status.

When I wrote all this for The Sunday Tribune in the wake of the 1994 IRA ceasefire, the paper ran it past Hume for his comment. He angrily denied it, demanding, if my memory serves me correct, that it be withdrawn. But, to his credit, the then editor, Peter Murtagh stood by the story and it appeared the next day. (See: "Haughey and the Priest", Sunday Tribune, September 25th, 1994)

In his now almost infamous interview with the BBC, Seamus Mallon said that John Hume gave the Provos, i.e. Gerry Adams what they wanted in the United States, ‘a respectable image’.

Mallon is correct, inasmuch as John Hume’s most important role thereafter was to persuade key US politicians, from Clinton downwards, that he would not associate himself with Gerry Adams if he did not think he was genuine about leading the IRA out of violence.

One senior Irish diplomat put it more succinctly, if brutally: ‘He gave the good housekeeping seal of approval to the peace process’ – and, effectively, to Gerry Adams.

|

| One Irish diplomat said John Hume’s function in America was to give Adams his good housekeeping seal of approval |

It was a clever ploy which also served to tie Adams firmly into the process, even though some will dispute whether this alone was sufficient to merit the awarding of the Nobel Peace Prize to Hume, a trophy which some say Adams himself secretly coveted.

The case that John Hume was therefore duped by both Charles Haughey and Gerry Adams during the peace process, that both men played him like a 3lb trout, is difficult to dispute. But Hume was not alone.

When the process began, it started in the IRA’s Army Council in 1988 when the seven wise men met and agreed to moderate the IRA’s terms for a British withdrawal.

A demand which as traditionally put, must be met within the lifetime of a British parliament could now happen, the Council decreed, over any length of years – twenty, even thirty – as long as the British formally and publicly announced an eventual intention to disengage and give a date when this would happen. In the interim, political arrangements and institutions were up for negotiation.

Talks and contacts on that basis were launched and feelers put out, via an sagairt, to Haughey, the Brits, John Hume and all.

But what we ended up with, the Good Friday Agreement and its various supplements, was that arrangement minus the British declaration to withdraw. That date for eventual British withdrawal was the unfilled gap in the still unpublished Hume-Adams agreement and leaving it unfilled was possibly the easiest but most significant task facing its architects.

When asked how Gerry Adams and his allies in Sinn Fein and the IRA completed this extraordinary assignment and delivered their more militant comrades to a process that ordinarily they would have rejected, I can provide no better metaphor than the one Bernadette McAliskey supplied many years ago.

The IRA, she would say, was like a fly caught in the neck of a bottle, struggling to escape upwards while all the time being pushed down the slippery glass with a stick. The pokes of the stick represented all the inducements to Sinn Fein – the visas to America, the prospect of Oval Office access, the support of Wall Street millionaires, the good election results, the new flood of American money, the media respectability, the whiff of leather from the back seat of ministerial cars – and the speechless anger of Unionists and Loyalists.

Eventually the fly can struggle no more and exhausted, it slides past the neck and falls, plop, into the pool of stagnant wine at the bottom of the bottle where it drowns.

Seamus Mallon’s analogy of Sinn Fein playing Hume like a 3 pound trout is a good one. But it is insufficient to tell the full story.

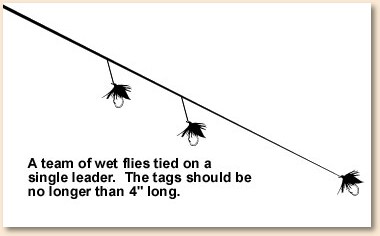

Seamus was, as far as I know, mostly a dry fly man, in particular a fan of the single, big fat Mayfly that floats, temptingly, on the lake or river surface; but a wet fly angler often casts a dropper with several flies tied to it that sink and seem to the fish to be drowned, vulnerable flies or nymphs struggling to the surface. Using a trace like this, it is not unknown for a skilled and lucky wet fly angler to hook more than one trout at a time.

|

| A wet fly trace |

That, I would argue, is the real story of the peace process: Sinn Fein, especially its leader, Gerry Adams, playing more than one big trout at the one time on a wet fly trace, one or two of them a good deal heavier than three pounds.

John Hume may have been caught on one hook but he was not alone.

"Eventually the fly can struggle no more and exhausted, it slides past the neck and falls, plop, into the pool of stagnant wine at the bottom of the bottle where it drowns."

ReplyDeletedont you mean pool of green diesel where it floats. plop.

First real laugh of the day courtesy of JG

ReplyDeleteid like to apologise to all the people on this site i have been rude to over the years, especially yourself, however i do despise marxism and that gets the better of me sometimes. i intend on being a nicer person. cheers. ps, i despise green diesel bandits also, especially ones who knock or knocked around with 'marxists'.

ReplyDeletewe don't do apologies here or demand that our critics wear hair shirts. We just get on with it. But if you want to donate a bottle of poteen we could reconsider!!

ReplyDeletesound

ReplyDeleteJerome G...

ReplyDeleteFunny how everything that was feared would come true under Marxism has been outmatched by wanton Capitalism..

How much a litre for diesel around Ballybinaby?

i dont know, but heres a good one for you;

ReplyDeletedid you know the word 'slab' means a plastic case containing a coin that has been graded and encapsulated.

how apt.

Jerome G,

ReplyDeleteNow that made me laugh! Cheers!

Whats not mentioned in the article is the normalisation of hopelessness throughout the entire period, particularly the stark empty unreality of day to day life in both communities.The degeneration of physical,mental, and spiritual health - the dead hands of corpses on the levers of power.

ReplyDeleteDear AM,

ReplyDeleteEd's article strikes to the core, I think, and there will be more forthcoming. I hope for full disclosure soon.

I remember well the serious and sometimes acrimonious arguments [70s to 90s] with Sinn Fein members in Belfast and elsewhere who defended US interests and foreign policy.

The people involved were usually ignorant but very single minded; I began to fear the 'religion' that was being formed based on a superficial fantasy of US benevolence, Catholic authority and neoliberal advantages.

So Jerome, what is in Marx's ideas that upsets you so much?