Those of us who lived through the Troubles, especially the early years, know the tale well.

It is the story of how a campaign for civil rights spiraled out of control and became a war that would be long, bloody and intractable, so unaccommodating to a solution that it lasted the best part of a quarter of a century, touched nearly every person in Northern Ireland and took more than a decade of frustratingly slow diplomacy to end. And it hasn’t really ended, even yet.

The story of how this happened in a small, insignificant place like Northern Ireland, is one that America would do well to study with care as the country gears up for a presidential election next year that looks set, short of a dramatic reversal in ISIS’ fortunes, to be dominated by demands for a full-blooded response to ISIS’ threats to bring its violence to America’s streets.

The parallels are far from exact of course. The cultural differences are vast, the historical background very different, the scale of violence and loss of life, actual and potential, puts Northern Ireland in the ha’penny place and, of course, the capacity for world-wide instability an ever-present threat in a way that was never the case in the North.

Nonetheless warfare is warfare and human beings are human beings, and that being the case it seems to me that the one universal lesson that can be learned from the Northern Ireland experience is the stupidity of knee jerk reactions, especially when deliberately provoked.

In this regard, I have in mind as a lesson for America’s handling of ISIS, the background to the introduction of internment in August 1971, the enormous boost this gave to the IRA, and the utterly transformative impact it had on the politics of Northern Ireland.

In early 1971, the Provisional IRA was growing, but only slowly and hardly at all outside of Belfast. What military success it did enjoy was down to the fact that its ranks were being filled by young men and women with no family record of involvement in republicanism and therefore no police file.

It is easily forgotten now, but the IRA of the 1950’s and 1960’s was largely shunned by Northern Ireland’s Catholics, primarily because to do so risked the unwelcome and hostile attention of the Royal Ulster Constabulary (RUC), and could lead to problems at work, like being sacked. The IRA was small and its membership well known to the Special Branch. As long as it stayed like that it posed no real threat to the state.

But the Loyalist-led, attempted pogrom of August 1969 in West and North Belfast in response to the civil rights marches had attracted a new generation of Catholic recruits, driven by the imperative to defend their areas rather than ideology and who were largely unknown to the RUC.

The old, pre-1969 IRA could be neutralised in a couple of well-directed internment swoops, as had happened in almost every decade since the foundation of the state; but not the new Provisional IRA, whose make-up was largely a blank sheet of paper to the RUC.

This was a great advantage to the IRA but some of its leaders in Belfast knew this was a likely temporary advantage. Eventually the Special Branch, augmented now by British military intelligence, would get their act together and the post-1969 IRA would become known and therefore vulnerable at some point in the not too distant future.

The Belfast leadership knew that internment would come – but it calculated that the sooner this happened, the better. A plan was laid to force the British into a premature and ill-prepared strike, carried out before the IRA became exposed; but its success was entirely dependent upon the IRA’s opponents reacting in a predictably intemperate fashion.

In 1971, Northern Ireland was still governed from Stormont by a Unionist-dominated parliament and government. Led by Brian Faulkner, the Unionist cabinet was under intense pressure from its own right-wing and from a rabble-rousing Ian Paisley. IRA violence and concessions to the civil rights campaign had unnerved the Unionist grassroots, demands to resist Nationalist encroachment were growing and Faulkner’s political survival was questionable.

While the British government in London had final responsibility for Northern Ireland it was desperate to avoid a closer entanglement. Direct Rule from London was the only alternative to Stormont, but while it was easy to begin, it would be devilishly difficult to end. It was therefore an option to avoid, if possible.

The British government’s priority then was to prop up Faulkner, even if that meant bending to his right-wing and embracing security measures that might be distasteful and controversial.

Fully aware of all these pressure points and knowing that the circumstances could not be more propitious, the IRA in Belfast set out in the Spring and early Summer of 1971 to exploit them to the full and force the British into a premature and ill-prepared internment swoop.

And so, spurred on by a strategically gifted, 23-year-old commander of the Second Belfast Battalion called Gerry Adams, the IRA began a destructive economic bombing campaign in Belfast that soon had Unionists screaming for internment.

The high point of the campaign, if such it can be called, was a provocative series of bombs along the route of the Twelfth Orange parade that exploded the night before. Belfast Orangemen marching to the field at Finaghy that July 12th morning, had to walk past devastated store fronts, the twisted remnants of car bombs, and wrecked buildings, all testament to this new threat to their supremacy.

And so, internment without trial was introduced within weeks. Old RUC Special Branch records were scoured for lists of suspects and, as Adams and his allies predicted, the new Provisional IRA escaped largely unscathed when the troops raided homes in Belfast and elsewhere.

Meanwhile the one-sided nature of the internment operation – only Republicans and Nationalists were targeted – combined with the reality that largely innocent or no longer involved people had been targeted, served to deepen Catholic anger and in protest a wide spectrum of that community withdrew almost wholesale from public life.

It is now a generally accepted truth that the internment operation of August 1971 was a major turning point in the Troubles. Not only did the communal anger in Catholic districts boost recruitment to the IRA in Belfast and in rural areas where previously it barely existed – and arguably laid the foundations for the subsequent political strength of Sinn Fein – it also marked a point at which the Nationalist population as a whole signaled that there could never be a return to the Northern Ireland of old.

But all of this was only made possible because the British gave into the demand from Unionists for a response to match the IRA’s violence. Or, to put it another way, the IRA had laid a trap and the Unionists and British had walked right into it.

I don’t know whether the leaders of ISIS have studied the history of the Troubles and I doubt whether they need to. After all, the story of how internment transformed the conflict in Northern Ireland is really as old as warfare itself, being essentially an illustration of how to provoke an adversary into an act of self-defeating stupidity.

We are, arguably, at a point in the U.S. almost equivalent to Northern Ireland in the early summer of 1971. ISIS has delivered violence in the U.S. and threatens to deliver more in the hope that the Americans, like the Unionists, will demand like for like.

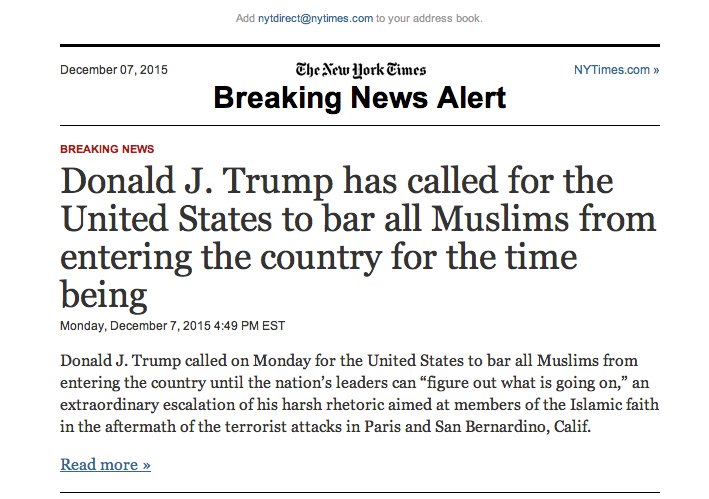

President Obama has given a response that the British and Unionists would have been sensible to have given forty-four years ago, but did not, could not, would not. Similarily, the gut American response is to revile Obama and instead follow the lead given by Donald Trump, the Ian Paisley, surely, of the United States:

|

A disaster beckons. To understand the full meaning of that prediction, I really do recommend that readers should revisit, or visit for the first time, Rajiv Chanderasekaran’s brilliantly entertaining, if ultimately depressing account of American rule in post-invasion Iraq: ‘Imperial Life in the Emerald City’.

The people he writes about are the same sorts currently crawling up walls in anger all over America in the wake of the slaughter in San Bernardino. A delighted ISIS can only grin in anticipation, much like the IRA hierarchy did in 1971.

Here is a sample from the opening chapter:

Chapter 1

Versailles on the Tigris

UNLIKE ALMOST ANYWHERE else in Baghdad, you could dine at the cafeteria in the Republican Palace for six months and never eat hummus, flatbread, or a lamb kebab. The fare was always American, often with a Southern flavor. A buffet featured grits, cornbread, and a bottomless barrel of pork: sausage for breakfast, hot dogs for lunch, pork chops for dinner. There were bacon cheeseburgers, grilled-cheese-and-bacon sandwiches, and bacon omelets. Hundreds of Iraqi secretaries and translators who worked for the occupation authority had to eat in the dining hall. Most of them were Muslims, and many were offended by the presence of pork. But the American contractors running the kitchen kept serving it. The cafeteria was all about meeting American needs for high-calorie, high-fat comfort food.

None of the succulent tomatoes or the crisp cucumbers grown in Iraq made it into the salad bar. U.S. government regulations dictated that everything, even the water in which hot dogs were boiled, be shipped in from approved suppliers in other nations. Milk and bread were trucked in from Kuwait, as were tinned peas and carrots. The breakfast cereal was flown in from the United States–made-in-the-USA. Froot Loops and Frosted Flakes at the breakfast table helped boost morale.

When the Americans had arrived, there was no cafeteria in the palace. Saddam Hussein had feasted in an ornate private dining room and his servants had eaten in small kitchenettes. The engineers assigned to transform the palace into the seat of the American occupation chose a marble-floored conference room the size of a gymnasium to serve as the mess hall. Through its gilded doors, Halliburton, the defense contractor hired to run the palace, brought in dozens of tables, hundreds of stacking chairs, and a score of glass-covered buffets. Seven days a week, the Americans ate under Saddam’s crystal chandeliers.

Red and white linens covered the tables. Diners sat on chairs with maroon cushions. A pleated skirt decorated the salad bar and the dessert table, which was piled high with cakes and cookies. The floor was polished after every meal.

A mural of the World Trade Center adorned one of the entrances. The Twin Towers were framed within the outstretched wings of a bald eagle. Each branch of the U.S. military–the army, air force, marines, and navy–had its seal on a different corner of the mural. In the middle were the logos of the New York City Police and Fire departments, and atop the towers were the words thank god for the coalition forces & freedom fighters at home and abroad.

At another of the three entrances was a bulletin board with posted notices, including those that read

BIBLE STUDY–WEDNESDAYS AT 7 P.M.

GO RUNNING WITH THE HASH HOUSE HARRIERS!

FEELING STRESSED? COME VISIT US AT THE COMBAT STRESS CLINIC.

FOR SALE: LIKE-NEW HUNTING KNIFE.

LOST CAMERA. REWARD OFFERED.

The kitchen, which had once prepared gourmet meals for Saddam, had been converted into an institutional food—processing center, with a giant deep fryer and bathtub-size mixing bowls. Halliburton had hired dozens of Pakistanis and Indians to cook and serve and clean, but no Iraqis. Nobody ever explained why, but everyone knew. They could poison the food.

The Pakistanis and the Indians wore white button-down shirts with black vests, black bow ties, and white paper hats. The Kuwaiti subcontractor who kept their passports and exacted a meaty profit margin off each worker also dinned into them American lingo. When I asked one of the Indians for French fries, he snapped: “We have no French fries here, sir. Only freedom fries.”

The seating was as tribal as that at a high school cafeteria. The Iraqi support staffers kept to themselves. They loaded their lunch trays with enough calories for three meals. Between mouthfuls, they mocked their American bosses with impunity. So few Americans in the palace spoke Arabic fluently that those who did could have fit around one table, with room to spare.

Soldiers, private contractors, and mercenaries also segregated themselves. So did the representatives of the “coalition of the willing”– the Brits, the Aussies, the Poles, the Spaniards, and the Italians. The American civilians who worked for the occupation government had their own cliques: the big-shot political appointees, the twentysomethings fresh out of college, the old hands who had arrived in Baghdad in the first weeks of occupation. In conversation at their tables, they observed an unspoken protocol. It was always appropriate to praise “the mission”–the Bush administration’s campaign to transform Iraq into a peaceful, modern, secular democracy where everyone, regardless of sect or ethnicity, would get along. Tirades about how Saddam had ruined the country and descriptions of how you were going to resuscitate it were also fine. But unless you knew someone really, really well, you didn’t question American policy over a meal.

If you had a complaint about the cafeteria, Michael Cole was the man to see. He was Halliburton’s “customer-service liaison,” and he could explain why the salad bar didn’t have Iraqi produce or why pork kept appearing on the menu. If you wanted to request a different type of breakfast cereal, he’d listen. Cole didn’t have the weathered look of a war-zone concierge. He was a rail-thin twenty-two-year-old whose forehead was dotted with pimples.

He had been out of college for less than a year and was working as a junior aide to a Republican congressman from Virginia when a Halliburton vice president overheard him talking to friends in an Arlington bar about his dealings with irate constituents. She was so impressed that she introduced herself. If she needed someone to work as a valet in Baghdad, he joked, he’d be happy to volunteer. Three weeks later, Halliburton offered him a job. Then they asked for his résumé.

Cole never ate pork products in the mess hall. He knew many of the servers were Pakistani Muslims and he felt terrible that they had to handle food they deemed offensive. He was rewarded for his expression of respect with invitations to the Dickensian trailer park where the kitchen staff lived. They didn’t have to abide by American rules governing food procurement. Their kitchens were filled with local produce, and they cooked spicy curries that were better than anything Cole found in the cafeteria. He thought of proposing an Indian- Pakistani food night at the mess hall, but then remembered that the palace didn’t do ethnic fare. “The cooking had to make people feel like they were back at home,” he said. And home, in this case, was presumed to be somewhere south of the Mason-Dixon Line.

Cole’s mission was to keep the air in the bubble, to ensure that the Americans who had left home to work for the occupation administration felt comfortable. Food was part of it. But so were movies, mattresses, and laundry service. If he was asked for something, Cole tried to get it, whether he thought it important or not. “Yes, sir. We’ll look into that,” he’d say. Or, “I’m sorry you’re so upset. We’ll try to fix it as soon as possible.”

The palace was the headquarters of the Coalition Provisional Authority, the American occupation administration in Iraq. From April 2003 to June 2004, the CPA ran Iraq’s government–it enacted laws, printed currency, collected taxes, deployed police, and spent oil revenue. At its height, the CPA had more than 1,500 employees in Baghdad, most of them American. They were a motley bunch: businessmen who were active in the Republican Party, retirees who wanted one last taste of adventure, diplomats who had studied Iraq for years, recent college graduates who had never had a full-time job, government employees who wanted the 25 percent salary bonus paid for working in a war zone. The CPA was headed by America’s viceroy in Iraq, Lewis Paul Bremer III, who always wore a blue suit and tan combat boots, even on those summer days when Iraqis drooped in the heat. He was surrounded by burly, machine gun—toting bodyguards everywhere he went, even to the bathroom in the palace.

The palace was Versailles on the Tigris. Constructed of sandstone and marble, it had wide hallways, soaring columns, and spiral staircases. Massive bronze busts of Saddam in an Arab warrior’s headdress looked down from the four corners of the roof. The cafeteria was on the south side, next to a chapel with a billboard-size mural of a Scud missile arcing into the sky. In the northern wing was an enormous ballroom with a balcony overlooking the dance floor. The heart of the palace was a giant marble rotunda with a turquoise dome. After the Americans arrived, the entire place took on the slapdash appearance of a start-up company. Dell computers sat atop ornate wooden desks partitioned by fabric-covered cubicle dividers. Data cables snaked along the gilded moldings. Erasable whiteboards hung from the mirrored walls.

A row of portable toilets lined the rear driveway. The palace, designed as a showplace for Saddam to meet visiting dignitaries, lacked enough commodes for hundreds of occupants. Dormitory space was also in short supply. Most new arrivals had to sleep on bunk beds in the chapel, a room that came to resemble a World War II field hospital.

Appearances aside, the same rules applied in the palace as in any government building in Washington. Everyone wore an identification badge. Decorum was enforced in the high-ceilinged halls. I remember hearing a soldier admonish a staffer hustling to a meeting: “Ma’am, you must not run in the corridor.”

Whatever could be outsourced was. The job of setting up town and city councils was performed by a North Carolina firm for $236 million. The job of guarding the viceroy was assigned to private guards, each of whom made more than $1,000 a day. For running the palace–cooking the food, changing the lightbulbs, doing the laundry, watering the plants– Halliburton had been handed hundreds of millions of dollars.

Halliburton had been hired to provide “living support” services to the CPA. What that meant kept evolving. When the first Americans arrived in Baghdad in the weeks after Saddam’s government was toppled, all anyone wanted was food and water, laundry service, and air-conditioning. By the time Cole arrived, in August 2003, four months into the occupation, the demands had grown. The viceroy’s house had to be outfitted with furniture and art suitable for a head of state. The Halliburton-run sports bar at the al-Rasheed Hotel needed a Foosball table. The press conference room required large-screen televisions.

The Green Zone quickly became Baghdad’s Little America. Everyone who worked in the palace lived there, either in white metal trailers or in the towering al-Rasheed. Hundreds of private contractors working for firms including Bechtel, General Electric, and Halliburton set up trailer parks there, as did legions of private security guards hired to protect the contractors. The only Iraqis allowed inside the Green Zone were those who worked for the Americans or those who could prove that they had lived there before the war.

It was Saddam who first decided to turn Baghdad’s prime riverfront real estate into a gated city within a city, with posh villas, bungalows, government buildings, shops, and even a hospital. He didn’t want his aides and bodyguards, who were given homes near his palace, to mingle with the masses. And he didn’t want outsiders peering in. The homes were bigger, the trees greener, the streets wider than in the rest of Baghdad. There were more palms and fewer people. There were no street vendors and no beggars. No one other than members of Saddam’s inner circle or his trusted cadre of guards and housekeepers had any idea what was inside. Those who loitered near the entrances sometimes landed in jail. Iraqis drove as fast as they could on roads near the compound lest they be accused of gawking.

It was the ideal place for the Americans to pitch their tents. Saddam had surrounded the area with a tall brick wall. There were only three points of entry. All the military had to do was park tanks at the gates.

The Americans expanded Saddam’s neighborhood by a few blocks to encompass the gargantuan Convention Center and the al-Rasheed, a once- luxurious establishment made famous by CNN’s live broadcasts during the 1991 Persian Gulf War. They fortified the walls with seventeen- foot-high blast barriers made of foot-thick concrete topped with coils of razor wire.

Open spaces became trailer parks with grandiose names. CPA staffers unable to snag a room at the al-Rasheed lived in Poolside Estates. Cole and his fellow Halliburton employees were in Camp Hope. The Brits dubbed their accommodations Ocean Cliffs. At first, the Americans felt sorry for the Brits, whose trailers were in a covered parking garage, which seemed dark and miserable. But when the insurgents began firing mortars into the Green Zone, everyone wished they were in Ocean Cliffs. The envy increased when Americans discovered that the Brits didn’t have the same leaky trailers with plastic furniture supplied by Halliburton; theirs had been outfitted by Ikea.

Americans drove around in new GMC Suburbans, dutifully obeying the thirty-five-mile-an-hour speed limit signs posted by the CPA on the flat, wide streets. There were so many identical Suburbans parked in front of the palace that drivers had to use their electronic door openers as homing devices. (One contractor affixed Texas license plates to his vehicle to set it apart.) When they cruised around, they kept the air-conditioning on high and the radio tuned to 107.7 FM, Freedom Radio, an American-run station that played classic rock and rah-rah messages. Every two weeks, the vehicles were cleaned at a Halliburton car wash.

Shuttle buses looped around the Green Zone at twenty-minute intervals, stopping at wooden shelters to transport those who didn’t have cars and didn’t want to walk. There was daily mail delivery. Generators ensured that the lights were always on. If you didn’t like what was being served in the cafeteria–or you were feeling peckish between meals–you could get takeout from one of the Green Zone’s Chinese restaurants. Halliburton’s dry cleaning service would get the dust and sweat stains out of your khakis in three days. A sign warned patrons to remove ammunition from pockets before submitting clothes.

Iraqi laws and customs didn’t apply inside the Green Zone. Women jogged on the sidewalk in shorts and T-shirts. A liquor store sold imported beer, wine, and spirits. One of the Chinese restaurants offered massages as well as noodles. The young boys selling DVDs near the palace parking lot had a secret stash. “Mister, you want porno?” they often whispered to me.

Most Americans sported suede combat boots, expensive sunglasses, and nine-millimeter Berettas attached to the thigh with a Velcro holster. They groused about the heat and the mosquitoes and the slothful habits of the natives. A contingent of Gurkhas stood as sentries in front of the palace.

Great article, thanks EM.

ReplyDeleteWas the leadership then so astute considering their actions since?

ReplyDelete