First of all, credit where credit is due. The excellent military historian, Huw Bennett, now of Aberystwyth University, was the first person to discover this extraordinary document in the files at the Kew archives and to him should go the plaudits for bringing this important archive to light.

James Kinchin-White excavated it for thebrokenelbow.com during one of his many expeditions to Kew, and it was made available by myself to RTE for their recent documentary, ‘Collusion’, which was screened this week.

To call the Tuzo plan extraordinary seems somehow inadequate. In fact its brutality and cynicism makes perfect sense when viewed through the prism of Tuzo’s background and experience as a member of the British military elite during Britain’s painful, post-colonial retreat from world power to America’s junior military ally.

|

| General Harry Tuzo, with escorts, circa 1972 |

Prior to his posting as General Officer Commanding (GoC) of British troops in Northern Ireland (where he took over from someone rejoicing in the name of Vernon Erskine-Crum, an Indian Army veteran and aide to Lord Mountbatten when he was Viceroy to India), Harry Tuzo commanded a Gurkha Brigade in Borneo during an insurgency in the late 1960’s, which the British claimed had been inspired by an Indonesian regime suspected of being under Communist influence.

Born in Bangalore, India in 1917, Tuzo was a child of the British Raj, the colonial class which ruled the sub-continent from the days of the East India Company in the late 18th century onwards. His father was a British officer in the Royal Sussex Regiment and civil engineer who also saw service in East Africa. His mother, a memsahib, was the daughter of the Raj, her father an official in the Indian civil service. As a child, Harry Tuzo was sent home to England to prepare for a life of imperial service and was schooled at Wellington College and Oriel College, Oxford.

As things turned out Tuzo reached the apex of his miltary service in the twilight of empire. Like so many of his contemporaries, Northern Ireland was to be the last hurrah of a generation whose like would never be seen again: Tuzo, Kitson, Ford, Freeland, King, Wilsey and Creasey. Such names to conjure with!

Sliding effortlessly after Oxford into a military career that was guaranteed to bring rank and honours, and, in the aftermath of World War II, moving from one post-colonial skirmish to another, Tuzo was, in the summer of 1972, charged with devising a plan to combat and annihilate the Provisional IRA, in much the same way as his Gurkhas disposed of Indonesian rebels in Borneo, with maximum force and minimum fuss.

There are so many striking features of this episode that it is hard to know where to start, except to say that had Tuzo got his way, and had the IRA not pre-empted his scheme with its own piece of madness, Northern Ireland would almost certainly not be the place it is now; whether better or worse is a more difficult question to address.

To begin with, there is an assumption underlying the plan, which must have taken many days to prepare but which was presented to NI Secretary William Whitelaw only the day before the Lenadoon confrontation that brought the IRA’s ceasefire to a violent end; this was that the ceasefire was, in British eyes, never going to last and that the British were ready, even eager, for its end, and possibly conspiring to bring it to an end.

Whether that realisation dawned on the British after the futile meeting between the IRA’s leadership and Whitelaw at Cheyne Walk, just two days before, or that the ceasefire, dubbed ‘the Initiative’ by the British for some intriguing but unexplained reason, was never a serious proposition in their eyes, it is clear from Tuzo’s detailed and intricate proposal that the military had been anticipating a breakdown and the resumption of hostilities for some time before Lenadoon. And it is hard to read Tuzo’s plan and not think that the British military at least, were also eagerly anticipating such an outcome.

There are so many facets of the Tuzo plan worthy of discussion that it is hard to know where to begin. My inclination, however, is to let the reader absorb this document by him or herself rather than to steer them in any one direction. But a couple of features stand out.

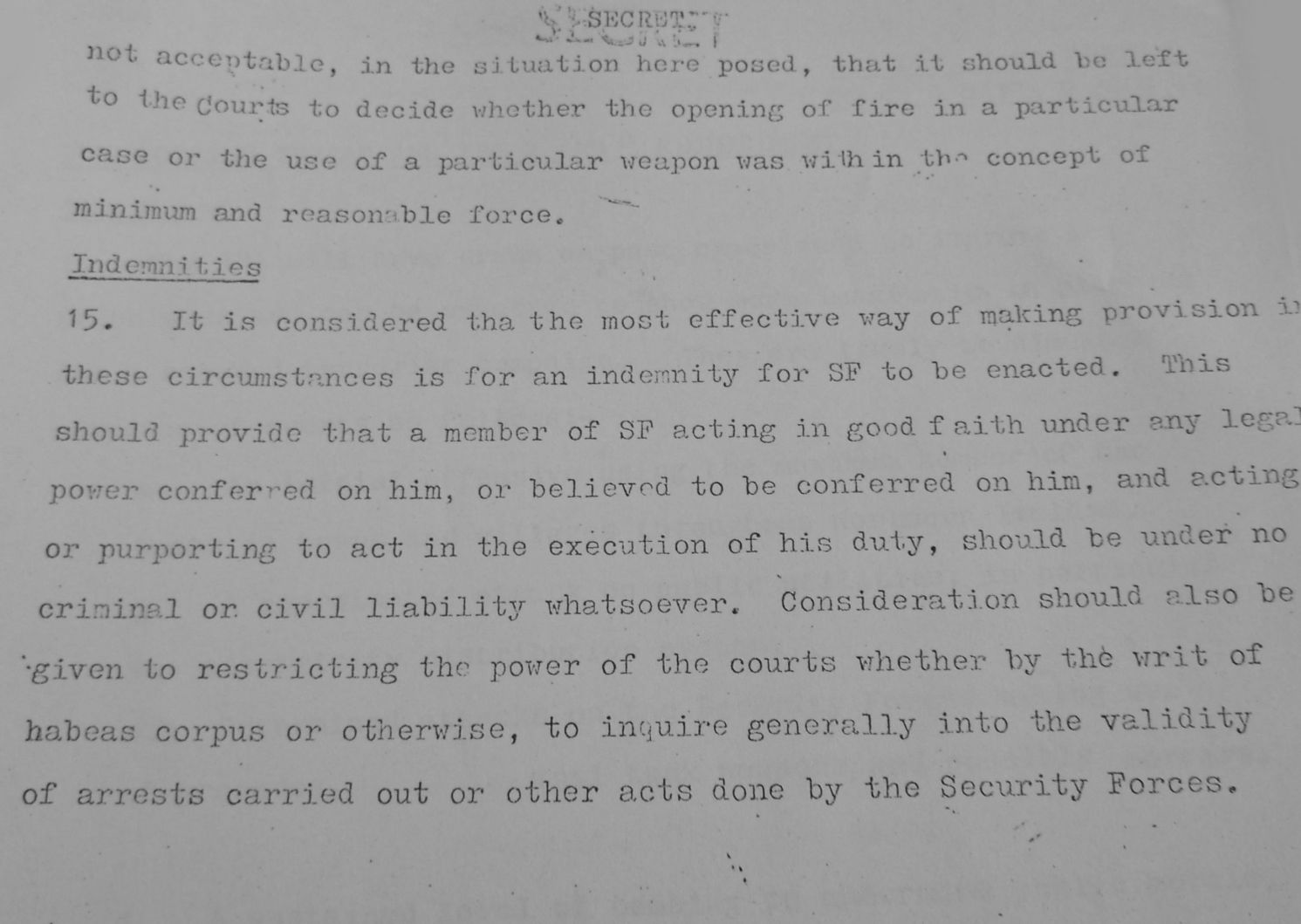

One was that the British were prepared to kill on a massive scale. The contemplation in the Tuzo plan of using Carl Gustav recoilless rifles in built-up, heavily populated areas such as the Bogside or Creggan allows for no other conclusion, for instance – and that is before you read about the creation of free-fire zones, the suspension of Yellow Card rules and legal changes that would entirely remove criminal or civil liability for soldiers who killed during the operation.

Below, see a more modern version of the Carl Gustav in action in US army hands and imagine it in use in Derry or West Belfast:

The other striking and politically significant aspect of the Tuzo plan is his willingness to use the Ulster Defence Association (UDA), which in 1972 had started to kill Catholics just because they were Catholics, as a de facto ally in the plan to extirpate the IRA.

So we read, for instance:

The major threat from the UDA is that their militant action will lead to widespread intersectarian conflict and eventually civil war, although strenuous military action against the IRA should prevent the latter…..It will be even more necessary to acquiesce in unarmed UDA patrolling and barricading of Protestant areas. Although no interference with security forces could be tolerated, it would be as well to make the best of the situation and obtain some security benefit from UDA control of their own areas. Indeed it is arguable that Protestant areas could almost entirely be secured by a combination of UDA, Orange Volunteers and RUC. It may even be necessary to turn a blind eye to UDA arms when confined to their own areas.

Shades of 1912, sixty years on, and a hint of an ambivalence towards Loyalist violence that would characterise British security policy thereafter and which now has returned to haunt British ministers and the search for a deeper, more firmly rooted peace in Northern Ireland.

General Harry Tuzo’s extraordinary plan to defeat and extinguish the IRA was never put into operation. We don’t even know whether William Whitelaw gave it his approval – the available documents say nothing about his response.

As it happened IRA militarism rendered the Tuzo scheme unnecessary. The bombs and carnage of Bloody Friday later that July turned the Catholic middle class and the SDLP decisively against the IRA and even sapped the enthusiasm of hardline IRA supporters; Tuzo was able to launch Operation Motorman with almost no Nationalist opposition, political or military.

The no-go areas of Derry were dismantled, Republican Belfast became one huge military base and the UDA returned to what it knew best, the random killing of innocent Catholics.

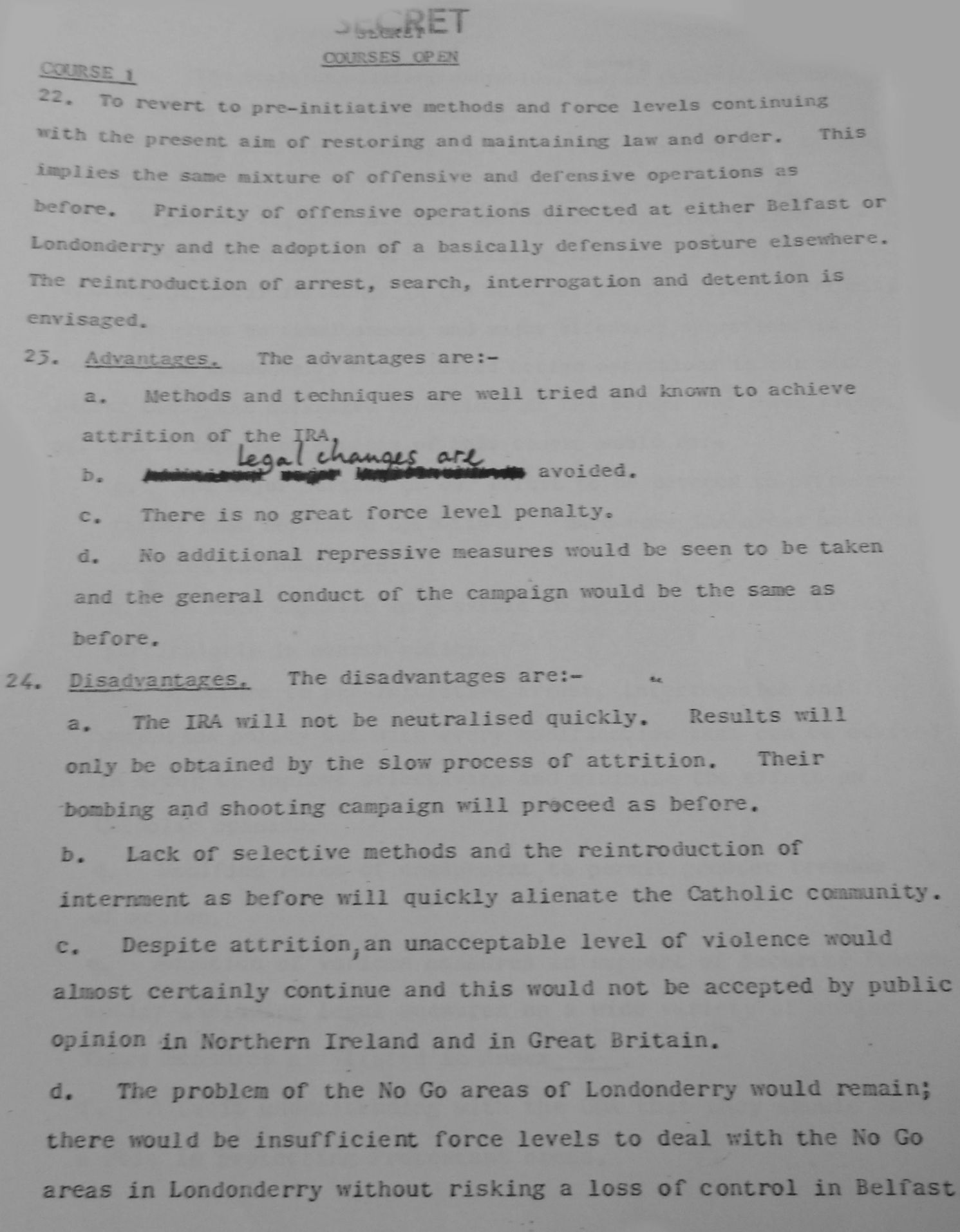

But in his ambitious plan, General Harry Tuzo revealed an essential truth about British policy in Northern Ireland: the British still would not take on the Loyalists.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

I find that extremely hard to read in the way it is scanned, but from what I can see it seems that Tuzo was basing his plans on the assumption that the IRA would put up a fight. We know from Motorman that they took themsleves off across the border until things had calmed down again and the bulkof the troops had been withdrawn.

ReplyDeleteIncidentally the Carl Gustav was in use throughout the Troubles. It was used by the bomb disposal teams.