As the more avid followers of the Jean McConville saga will remember, one of her sons, Michael McConville was abducted by the IRA – in fact by its youth wing, the Fianna – not long after his mother was taken away from her Divis Flats apartment in December 1972, tied up, beaten and threatened to keep his mouth shut about what or who he had seen.

The first of those reports came just a month after the ‘sitrep’ had reported the alleged abduction of a son of the woman whose disappearance was, in the last month of 1972 and opening weeks of 1973, the subject of considerable local media speculation and had attracted the concerned attention of the Northern Ireland Civil Rights Association and two Nationalist politicians, Paddy Devlin, MP at Stormont and Gerry Fitt, the Westminster MP for West Belfast.

To say that the military reports of February 12th 1973 and March 13th 1973 are in conflict is a bit of an understatement. If Jean McConville had contrived her own abduction why would men ‘in Combat kits’ want to kidnap one of her sons?

Notwithstanding Michael McConville’s credible denial, the ‘sitrep’ of February 12th, 1973 was not magicked out of thin air. It raises obvious questions: Where did it come from? Why was Michael named and not the other child? How solid was the intelligence? What was the follow up?

The information about the alleged abduction of Michael McConville was most likely derived from a ‘Watchkeeper’s Diary’, a ledger of all incidents and intelligence reports compiled in the operations room of all regimental units serving in Northern Ireland (see an example below) during the Troubles.

The operations room that covered Castle Street at that time was in Hastings Street RUC station, the base from which the IRA has claimed Jean McConville was ‘run’ as an agent.

Nuala O’Loan has consistently refused to say, to this and other reporters, whether the access she was given by the British security authorities during her probe of the McConville affair extended as far or as deep as documents such as ‘Watchkeepers’ Diaries’. But since she has admitted she had not heard of War Diaries when they were brought to her attention we can assume not, since War Diaries were also derived from ‘Watchkeepers’ Diaries’.

The answer to the mystery of Michael McConville’s second ‘abduction’ – in particular, if the boy was not abducted why did the military think he had been? – lies somewhere in the dusty files compiled by the British Army during the early 1970’s, only a fraction of which have even been made available for disclosure and many of which have been embargoed until the latter half of this century.

There may be an entirely innocent explanation for the ‘sitrep’, or it may open the way to deeper and darker questions. Either way the McConville family, and the rest of us, deserve the answer to this new mysterious twist in the story.

This matters because the suspicion that the British Army did employ Jean McConville as an informer stubbornly refuses to go away, not least because of the credibility of those like Brendan Hughes who detail the charge. Unlike other republicans embroiled in this tawdry affair, Hughes had no obvious motive to invent or embroider his account.

The IRA has, quite properly, been slated for the ghoulish disappearance of the widowed mother-of-ten. Crime of the Troubles might be taking it too far but her death and disappearance is certainly up there with the worst.

But what if the IRA was right and she did work for the British Army. What would that say about people who were happy – or ruthless enough – to employ a widow whose discovery by the IRA could, as they well knew, deprive ten children of their mother? The IRA and its then leaders certainly have a motive to mislead and misinform over the death of Jean McConville. But they may not be alone.

The story was first told on Darragh McIntyre’s TV documentary, ‘The Disappeared’, which was broadcast by the BBC in November 2013. This, in his own words, is what happened:

They pulled a hood over my head. It was a sleeve of a jumper, a wooly jumper because I could see through the mask. They took me down out of the Divis Flats into a house. They tied me to their chair, were hitting me with sticks, they were putting a gun to my head and they says they were going to shoot me. I had looked out of the side of my eye and there was a man and he was telling the younger ones what to do with me. So they had me, I would say, for about three hours and they said they were going to shoot me if I told anything about any member of the IRA, they would shoot me or other of my family members. They fired a gun, a cap gun and one of them stuck a penknife in my leg. They took me over to the Divis Flats and let me go at the stairs and I hobbled up the stairs into the house. I had just turned eleven at the time.

There was no official record of this incident and no mention of it in any British security file, although in an interview with thebrokenelbow.com, Michael McConville said he did tell the former NI police ombudsman, Nuala O’Loan about it when she was investigating her mother’s disappearance in 2005 and 2006.

However a separate report of another abduction incident allegedly involving Michael McConville has been unearthed recently at the British government’s official archive at Kew, Surrey.

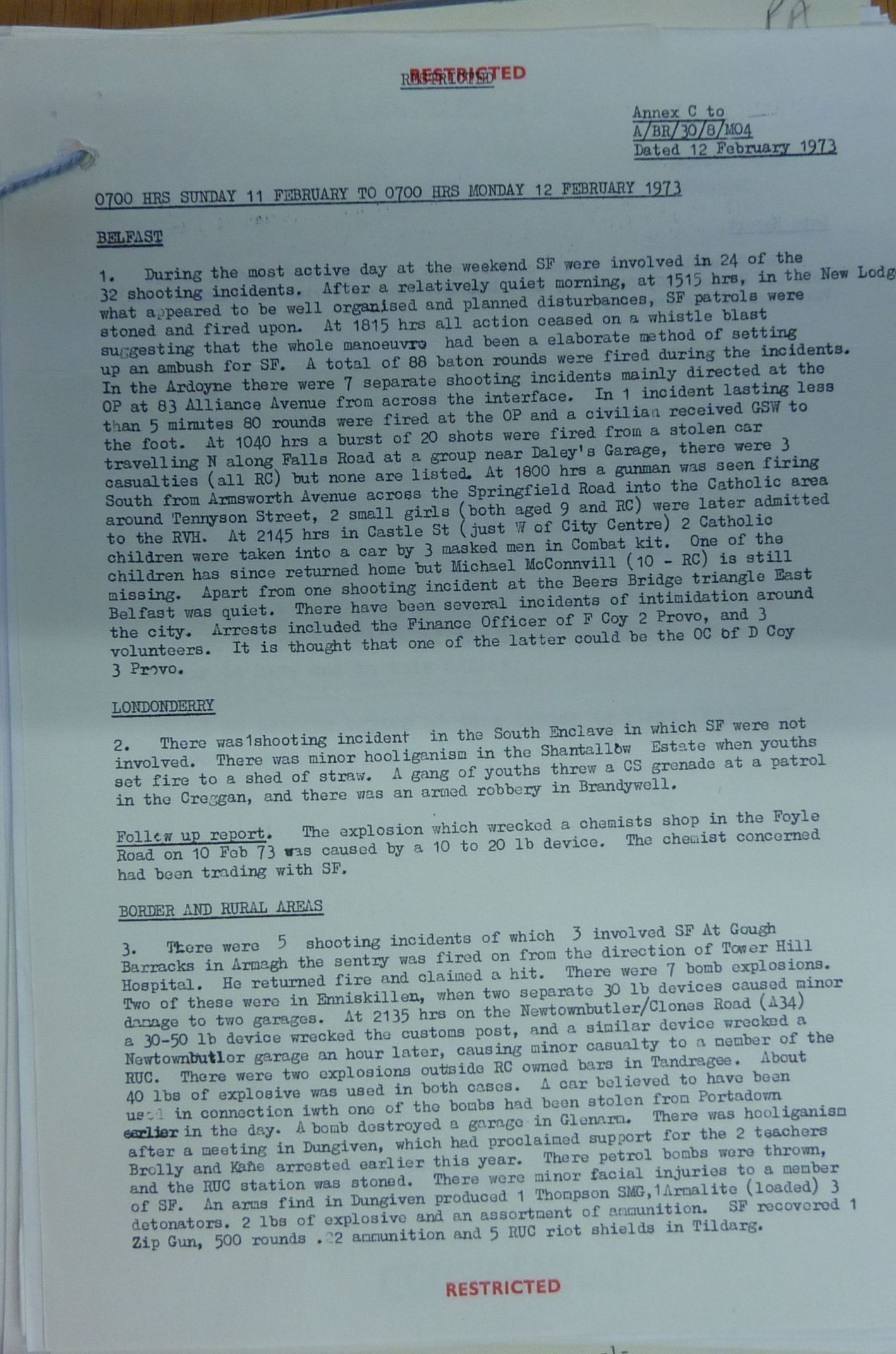

It is contained in a document called a ‘sitrep’, or daily situation report for February 12th, 1973, some two to three months after Jean McConville’s abduction and disappearance at the hands of the IRA.

Daily ‘sitreps’, or summaries of violent or paramilitary-linked incidents, were widely distributed within official British circles in those days when levels of violence were both intense and serious; thebrokenelbow.com understands that copies were routinely sent to British Army headquarters at Lisburn, Co Antrim, to the three Brigade HQ’s, to the head of RUC Special Branch, to the NIO and, probably, also to MI5/MI6, who were both active in Northern Ireland then.

A copy was also sent to 10 Downing Street, to the office of the British prime minister of the day. In February 1973, the prime minister was Ted Heath and this particular ‘sitrep’ was discovered in his file at the Kew archive.

The relevant section reads:

…..At 2145 hrs in Castle Street (just W of City Centre) 2 Catholic children were taken into a car by 3 masked men in Combat kit. One of the children has since returned home but Michael McConnvill (sic) (10-RC) is still missing.

The surname is misspelt – McConnvill instead of McConville – but the age is close – Michael had turned eleven the previous November – his religion was correct and Castle Street was, as he readily concedes, ‘his area’.

But as for the second alleged abduction, he is insistent that it never happened. “No, I was never taken away in a car. It definitely didn’t happen to me. The only time I was taken away was when they took me as I was walking to my grandmother’s.

Michael McConville’s abduction by the Fianna also took place some three months before the alleged second incident. It happened, he recalled, “….between a week and ten days of my mother (being taken away by the IRA). I’m not a hundred per cent sure but sometime in early December.” The precise date of Jean McConville’s abduction is not known but most accounts put it somewhere between late November and early December.

Whatever the truth about that aspect of the affair, the more than two month gap between the two ‘abduction’ incidents involving Michael McConville, one in early December 1972, the other in mid-February 1973, means that there is no chance that the two have been confused or conflated.

Nor does Michael McConville have any obvious motive for lying about the second ‘abduction’. There is no reason to disbelieve his denial. If anything his campaign to hold the IRA responsible for his family’s ills would only benefit if he was to confirm the second abduction. And he had told Nuala O’Loan about the first incident, so why not the second one?

The mystery of Michael McConville’s abduction or abductions does however raise some pertinent questions about Nuala O’Loan’s report into Jean McConville’s disappearance. Michael McConville said he told the police ombudsman about the incident but she did not follow up and made no reference to it in her final report.

“I didn’t tell Nuala the whole story of what happened to me”, he said in an interview over the phone. “I just told her I was taken away myself. I didn’t go into the details of it.” So did she question him about it? “Not that I remember.”

(Michael McConville added two new details to the account of his abduction. He said he gave Gerry Adams the names of two of the Fianna boys who abducted him. And he thinks that the man who gave orders to the Fianna boys was Brendan Hughes. “He was standing in the background and had a moustache. I think it was him although I am not 100 per cent sure.”)

Nuala O’Loan has yet to reply to two emails sent to her in March asking the relevant questions that arise from both the December 1972 abduction of Michael McConville and the ‘sitrep’ document of February 1973.

The emails asked these questions:

i was wondering whether you came across this document (the sitrep) during your inquiry and if so why it was not included in the list of documents that you did present given its direct relevance to the disappearing of jean mcconville? also i was wondering why you made no mention of michael mcconville’s (December 1972) abduction in your report. did he tell you about it at all?

In her 2006 report, Nuala O’Loan listed only two pieces of intelligence from the British Army dealing with the possible reasons for Jean McConville’s disappearance and both served to strengthen the case at the time to close the RUC file on her abduction.

These were:

- On 13 March 1973 information was received from the military suggesting that the abduction was an elaborate hoax;

- On 24 March 1973 further information was received from the military stating that the abduction was a hoax, that Mrs McConville had left of her own free will and was known to be safe.

The first of those reports came just a month after the ‘sitrep’ had reported the alleged abduction of a son of the woman whose disappearance was, in the last month of 1972 and opening weeks of 1973, the subject of considerable local media speculation and had attracted the concerned attention of the Northern Ireland Civil Rights Association and two Nationalist politicians, Paddy Devlin, MP at Stormont and Gerry Fitt, the Westminster MP for West Belfast.

To say that the military reports of February 12th 1973 and March 13th 1973 are in conflict is a bit of an understatement. If Jean McConville had contrived her own abduction why would men ‘in Combat kits’ want to kidnap one of her sons?

Notwithstanding Michael McConville’s credible denial, the ‘sitrep’ of February 12th, 1973 was not magicked out of thin air. It raises obvious questions: Where did it come from? Why was Michael named and not the other child? How solid was the intelligence? What was the follow up?

The information about the alleged abduction of Michael McConville was most likely derived from a ‘Watchkeeper’s Diary’, a ledger of all incidents and intelligence reports compiled in the operations room of all regimental units serving in Northern Ireland (see an example below) during the Troubles.

The operations room that covered Castle Street at that time was in Hastings Street RUC station, the base from which the IRA has claimed Jean McConville was ‘run’ as an agent.

Nuala O’Loan has consistently refused to say, to this and other reporters, whether the access she was given by the British security authorities during her probe of the McConville affair extended as far or as deep as documents such as ‘Watchkeepers’ Diaries’. But since she has admitted she had not heard of War Diaries when they were brought to her attention we can assume not, since War Diaries were also derived from ‘Watchkeepers’ Diaries’.

The answer to the mystery of Michael McConville’s second ‘abduction’ – in particular, if the boy was not abducted why did the military think he had been? – lies somewhere in the dusty files compiled by the British Army during the early 1970’s, only a fraction of which have even been made available for disclosure and many of which have been embargoed until the latter half of this century.

There may be an entirely innocent explanation for the ‘sitrep’, or it may open the way to deeper and darker questions. Either way the McConville family, and the rest of us, deserve the answer to this new mysterious twist in the story.

This matters because the suspicion that the British Army did employ Jean McConville as an informer stubbornly refuses to go away, not least because of the credibility of those like Brendan Hughes who detail the charge. Unlike other republicans embroiled in this tawdry affair, Hughes had no obvious motive to invent or embroider his account.

The IRA has, quite properly, been slated for the ghoulish disappearance of the widowed mother-of-ten. Crime of the Troubles might be taking it too far but her death and disappearance is certainly up there with the worst.

But what if the IRA was right and she did work for the British Army. What would that say about people who were happy – or ruthless enough – to employ a widow whose discovery by the IRA could, as they well knew, deprive ten children of their mother? The IRA and its then leaders certainly have a motive to mislead and misinform over the death of Jean McConville. But they may not be alone.

And he thinks that the man who gave orders to the Fianna boys was Brendan Hughes

ReplyDeleteIf this is true it is a bit sad because Brendan Hughes said his mum died when he was young and he had a lot of respect for his dad for looking after him and his siblings, Jean mcconville was in same position as his dad was and he was involved in her murder and then targeted her son after.