As 2015 began the thought suddenly hit me that this is the first New Year that has started without me either being in prison – or facing the possibility of trial, conviction and incarceration – since 1st January 2010. All in all, it has been a long five years. However, I still consider myself very fortunate when I think about the situations of so many people that I’ve met during my time in prison.

You do encounter all sorts of folk in the slammer, including many who have serious mental health problems and the elderly, but it’s often the youngest cons who tend to stick in the mind. Some of them look far too young to be banged up in an adult jail. A few seem like they should still be in school doing GCSEs rather than in a Cat-B local nick doing porridge, yet there they are, wandering along the landings at the age of 18.

|

| Young, vulnerable... and in an adult men's prison |

You tend to meet these lads in Cat-Bs simply because they are usually being held on remand awaiting trial often on serious charges, although not always. Sometimes its because they have already been convicted but are being assessed before transfer to Young Offender Institutions (YOIs). Anyone aged under 21 is officially considered to be a Young Prisoner (YP) and they aren’t supposed to share cells with adult cons – anyone aged over 21 – yet they can still spend months trying to survive on the wings of adult establishments which really don’t have the staff or the resources to look after them safely.

In some cases they are living with severe mental illness or serious personality disorders, while others are desperately immature even for teenagers. For many, prison is just the latest stage in a wretched journey from dysfunctional or abusive home lives, institutional care or the Youth Justice system. As a relative newcomer to the world of prison myself, I was astonished to find that these kids – because that is what most of them still are – can be banged up with much older adults while on remand or prior to being transferred to a YOI.

When you first see these YPs being led by a screw on to an adult wing fresh from Reception, you wonder just how they will survive. Sadly, a few don’t, but even those who do can’t fail to be scarred by their experiences among adult inmates.

As an Insider (peer mentor) in a large – and very overcrowded – Cat-B local nick, I was once asked by a fellow con to go and have a chat with a newly arrived YP. “I think he’s going to have problems,” was what he told me. Nothing prepared me for what I found when I knocked on the door of this lad’s cell on the Twos (first floor landing).

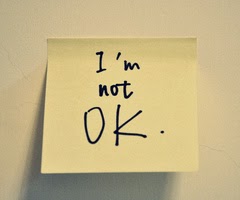

|

| Depression and despair in cell |

The boy – let’s call him ‘Sam’ (not his real name) – was sitting on the bottom bunk sobbing his heart out. He was 5ft 4”, skinny as a rake and looked about 14, although in fact he had just turned 18. I doubted that he had ever shaved in his life – or had needed to – and I was easily old enough to be his dad.

Down in the Reception stores they hadn’t been able to find him small enough prison gear to properly fit his slight frame. He was dressed in oversized grey prison joggers that he had to hold up when he walked and a light blue t-shirt that fitted him like a sack.

When I came into his pad (cell) and he saw that I wasn’t a screw in uniform he cowered into the corner, shaking with fear for reasons that became very clear a little later on. He obviously thought that I had come to do him harm of some kind. It took time and patience to convince him that although I was a fellow con, I had an official role as an Insider who might be able to help him through his time on remand at the nick.

In between bouts of tears it became clear that all he really wanted to do was to find a relatively painless way to kill himself. He was so terrified that the idea of dying seemed to be the only way he could cope with the reality of being locked up with 170 much older blokes, some of whom could easily have eaten him for breakfast.

|

| Trainers with long laces |

He was also distressed because the Reception screws had taken all his own clothing – including his trainers. Although prisoners on remand are entitled to wear their own clothes, this particular nick routinely ignored the rules.

Sam had found the initial strip search when he arrived to be deeply traumatic, again for reasons that became clear in due course, and he really wanted his own trainers back. Instead he had been given a pair of prison ‘Ranby Reeboks’ – gray canvas deck shoes with white rubber soles and velcro fasteners. It emerged that the main reason he wanted his trainers back was so he could tie the laces together to make a ligature with which to hang himself from the end of his bunk – the only way he could see out of his terrifying predicament at that moment.

Sam had found the initial strip search when he arrived to be deeply traumatic, again for reasons that became clear in due course, and he really wanted his own trainers back. Instead he had been given a pair of prison ‘Ranby Reeboks’ – gray canvas deck shoes with white rubber soles and velcro fasteners. It emerged that the main reason he wanted his trainers back was so he could tie the laces together to make a ligature with which to hang himself from the end of his bunk – the only way he could see out of his terrifying predicament at that moment.

At one point he even asked me whether I thought hanging would “hurt much”... a question posed with the wide-eyed innocence of a much younger child. I must admit that I had such a lump in my own throat that I felt like bursting into tears alongside him.

|

| Shoelace noose |

I’d been in prison long enough to be able to distinguish between real distress and new cons who were mere attention-seekers (and there are more than a few of these in any nick). In my view Sam was extremely vulnerable and at real risk of self-harm, perhaps even suicide. I spent most of the afternoon trying to calm him down and convince him that killing himself wasn’t his only option. The problem was that not only did he look about 14, he was so immature that he was functioning at the level of a child even younger than that.

A couple of months earlier, at the same prison and on the same wing, a severely depressed 21-year old on remand had actually committed suicide while on the highly punitive Basic regime. His death had had such an impact on those who knew him that none of us wanted another suicide, so there was a genuinely heightened sense of looking out for the more vulnerable prisoners in our midst.

That’s not to say that there weren’t plenty of low-life hyenas around who would have homed-in on such a vulnerable kid and stripped him of everything he had, which wasn’t much to start with, including his food. However, at that particular moment the ex-armed services veterans on the wing had the upper hand and we were doing our best, amid widespread staff indifference, to avoid any more tragedies.

Following the previous suicide on the wing, we had pretty much given up on the official ‘Safer Custody’ system – headed by an incompetent, and often inebriated, custodial manager – since she seemed far more interested in covering her own backside than actually reducing the risk of further suicides. In fact, when she decided to hold a wing meeting in the aftermath of the latest death on her watch, she made the mistake of asking if anyone had anything to say and one of the braver lads shouted down from an upper landing: “You have blood on your hands!” He was a lone voice, but he spoke for the majority of us.

|

| It's not always so obvious |

Our own informal network, which included liaison with other inmate support groups – such as the Samaritan-trained Listeners - as well as with the Chaplaincy team, probably did more to avert further suicides than any amount of bureaucratic so-called ‘Safer Custody’ meetings. We decided that Sam was not about to become the latest statistic at what even the HM Inspectorate of Prisons had condemned as an establishment in crisis.

So a small group of us provided support and protection. As the days went by, I got to know Sam better. If I had set out to write a classic British horror story, I could not have invented Sam’s life history. His violent drunk of a father started beating and raping him at the age of five. All his siblings, male and female, experienced the same sort of horrific violations and this went on for years, right under the noses of social services to whom the family was well-known. This young kid had experienced depths of misery and adult depravity that would break the heart of anyone with an ounce of empathy or compassion for others.

Even though Sam’s father is now serving a life sentence in jail for the crimes he committed against his own children, this hadn’t relieved the hurt or damage his son continues to live with every day of his life. The fact that he had been ‘self-medicating’ with drugs and alcohol throughout most of his teenage years in an effort to cope with the memories of his terrible childhood hardly came as a surprise, nor did his tendency to lash out in fear and anger at others when under their influence – hence his being remanded in custody after a serious assault.

|

| Frightened and behind bars |

I’d like to write here that when he went to court Sam was treated leniently and received the professional help he very obviously needed. Sadly, he was handed down a hefty prison sentence and was eventually transferred from the adult jail to a YOI. Who knows whether he is getting treatment that will assist him to turn his life around? I hope he is, but to be honest, I fear the worst especially after reading recent highly critical reports on some of our YOIs issued by HM Inspectorate of Prisons. These seem to be even more of a jungle environment where the strong fight to survive than most of our adult nicks.

Our prison system often simply warehouses deeply damaged kids and severely traumatised young people like Sam. I’ve come across them on Cat-B local wings, as well as after they have turned 21 and have been transferred from YOIs to the adult prison system. A fair few of them arrive with a serious drug habit, even if they didn’t have one when they were sent down. Many have complex needs that aren’t being addressed by simply banging them up in a tiny concrete box behind a heavy steel door and then hoping that they won’t self-harm or kill themselves in their depression and despair – thus contributing to what Chris Grayling has shamefully described as a recent “blip” in the suicide statistics.

Perhaps Sam was lucky that he found a few older inmates who were willing to let him speak about his problems while also looking out for him and keeping the hyenas and predators – of all sorts – at bay while he was living among us: a young, vulnerable and frightened kid on a jail wing full of adult men. He could easily have become just another statistic in the shamefully long list of people who have committed suicide in our increasingly overcrowded and understaffed prisons.

VIDEO: Florida Deputy Drags Shackled Women Through Courthouse By Her Feet

ReplyDelete